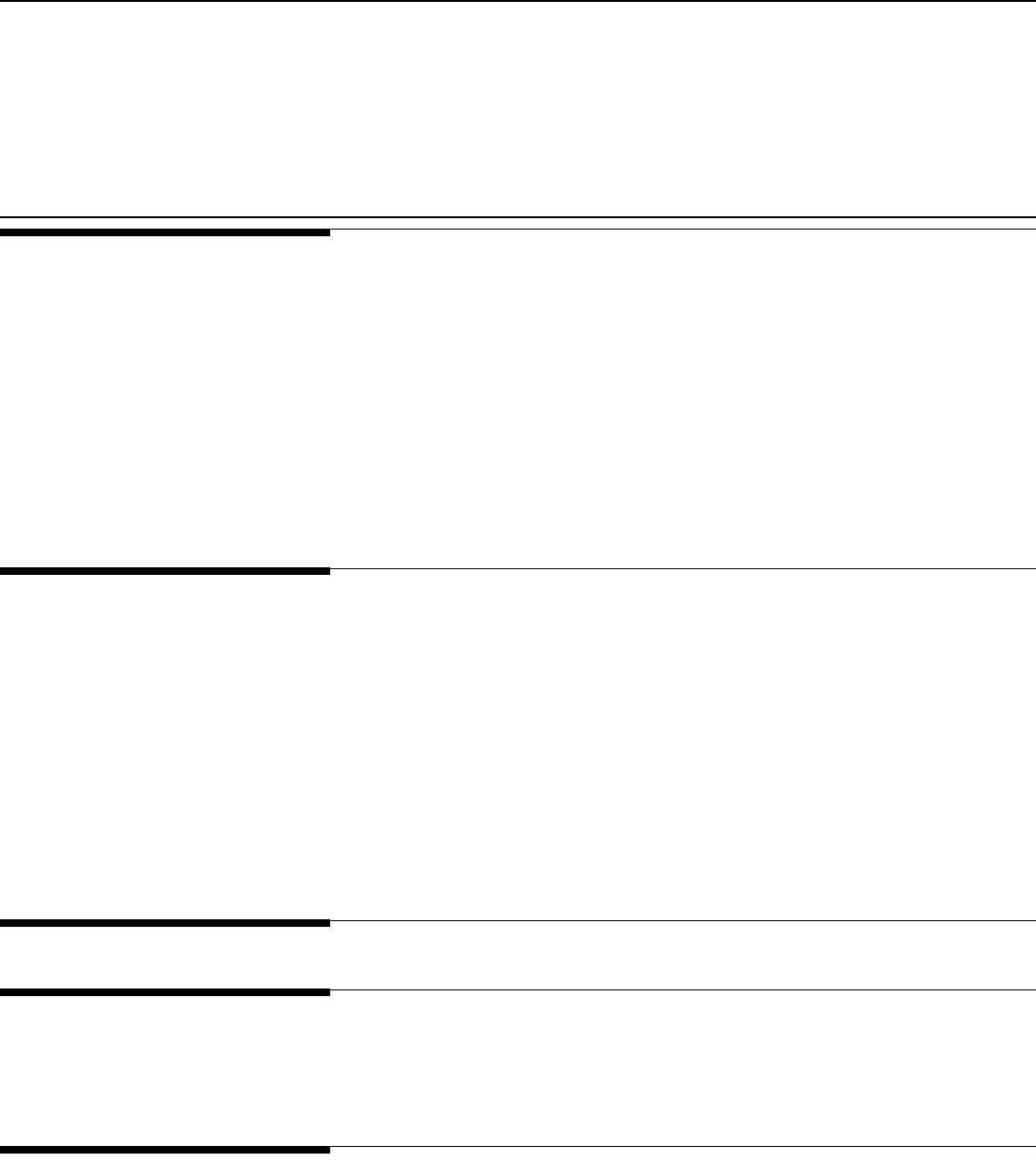

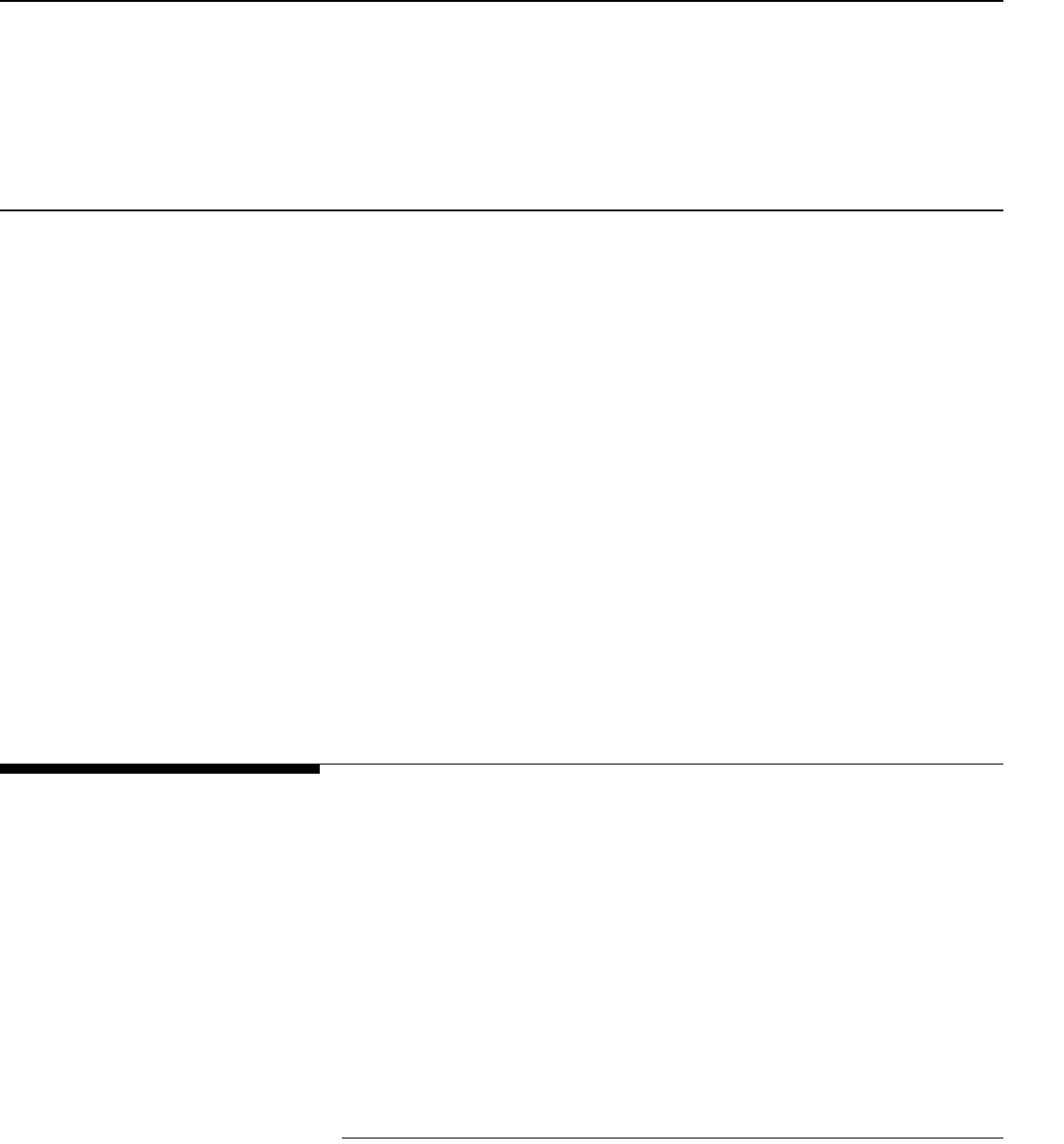

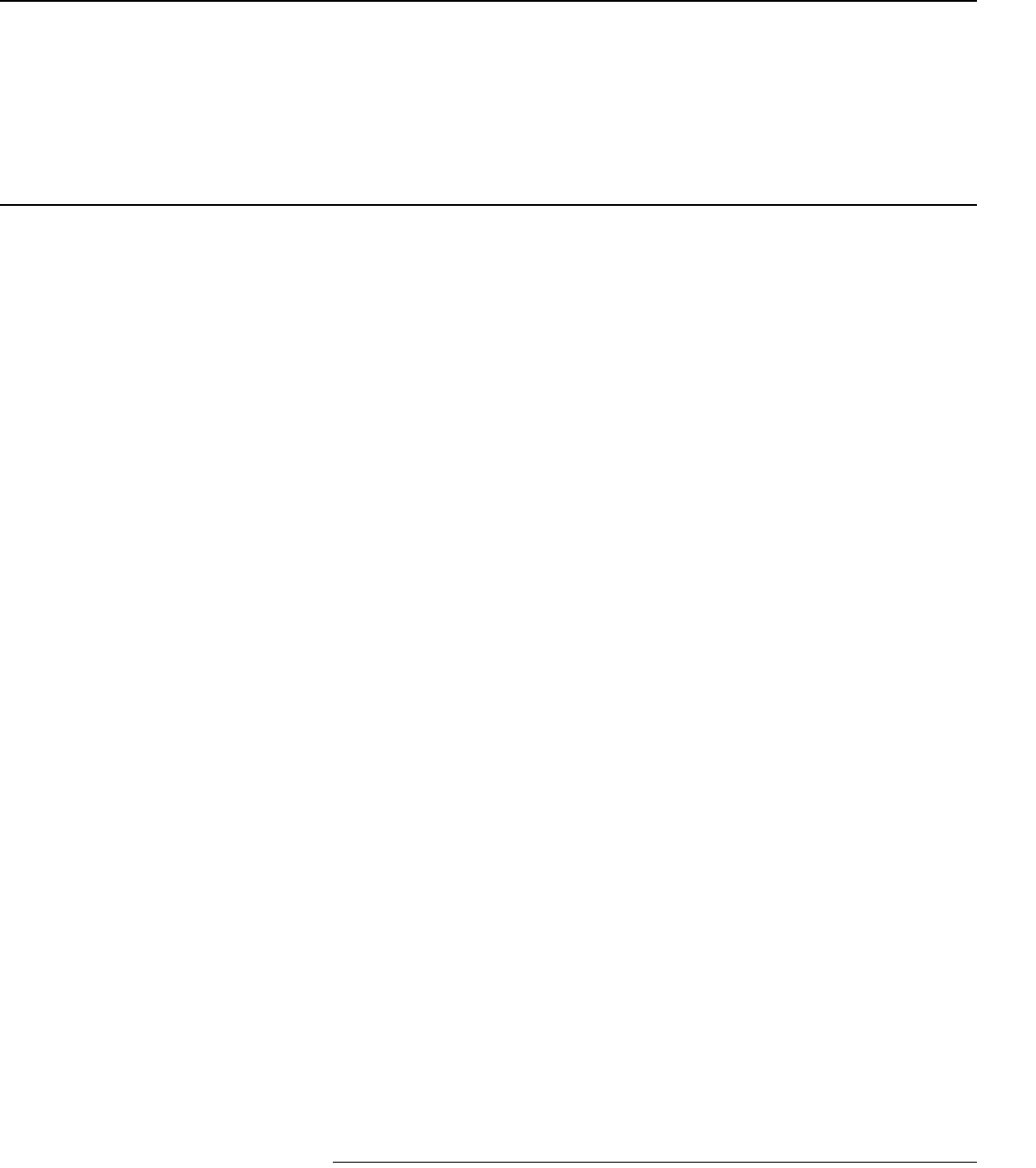

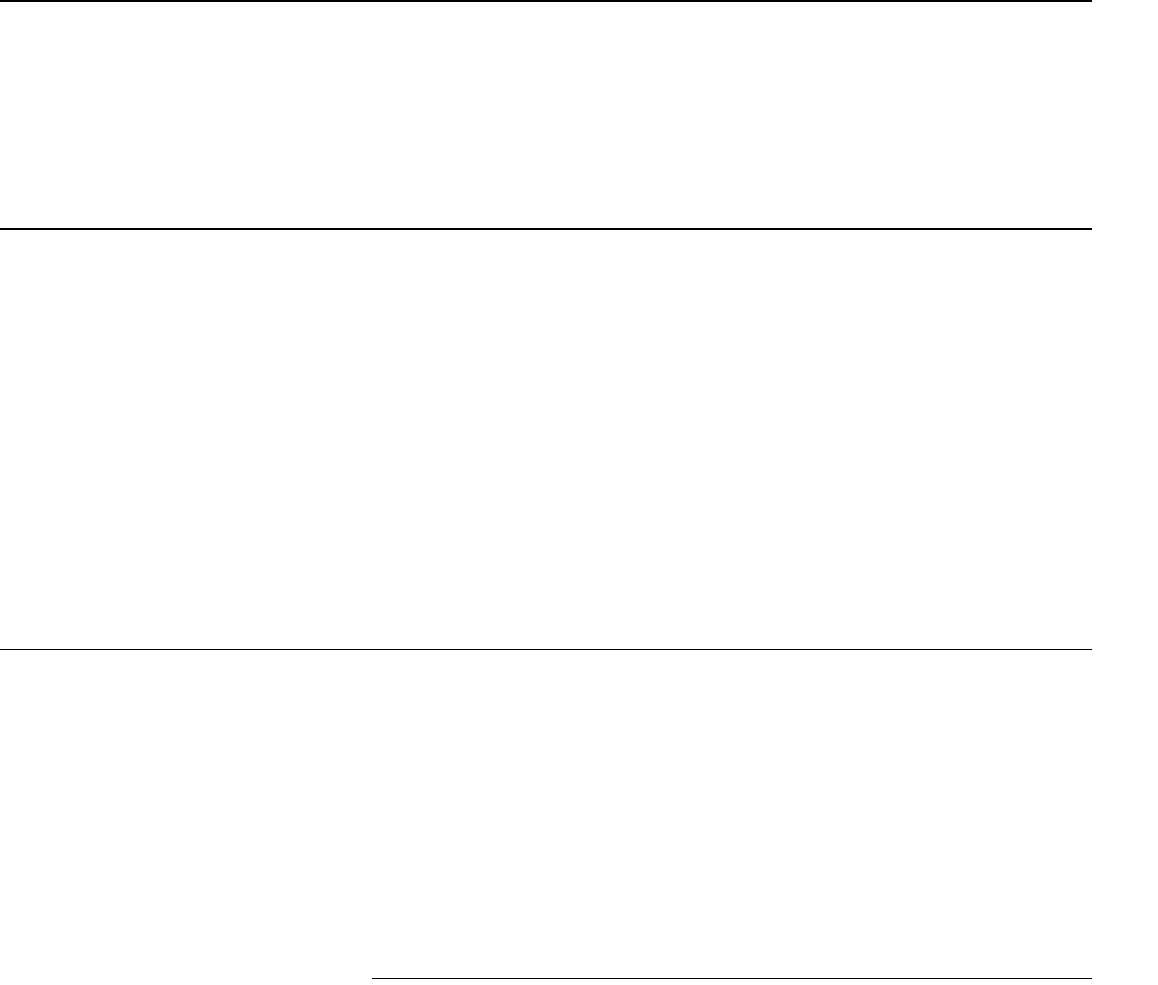

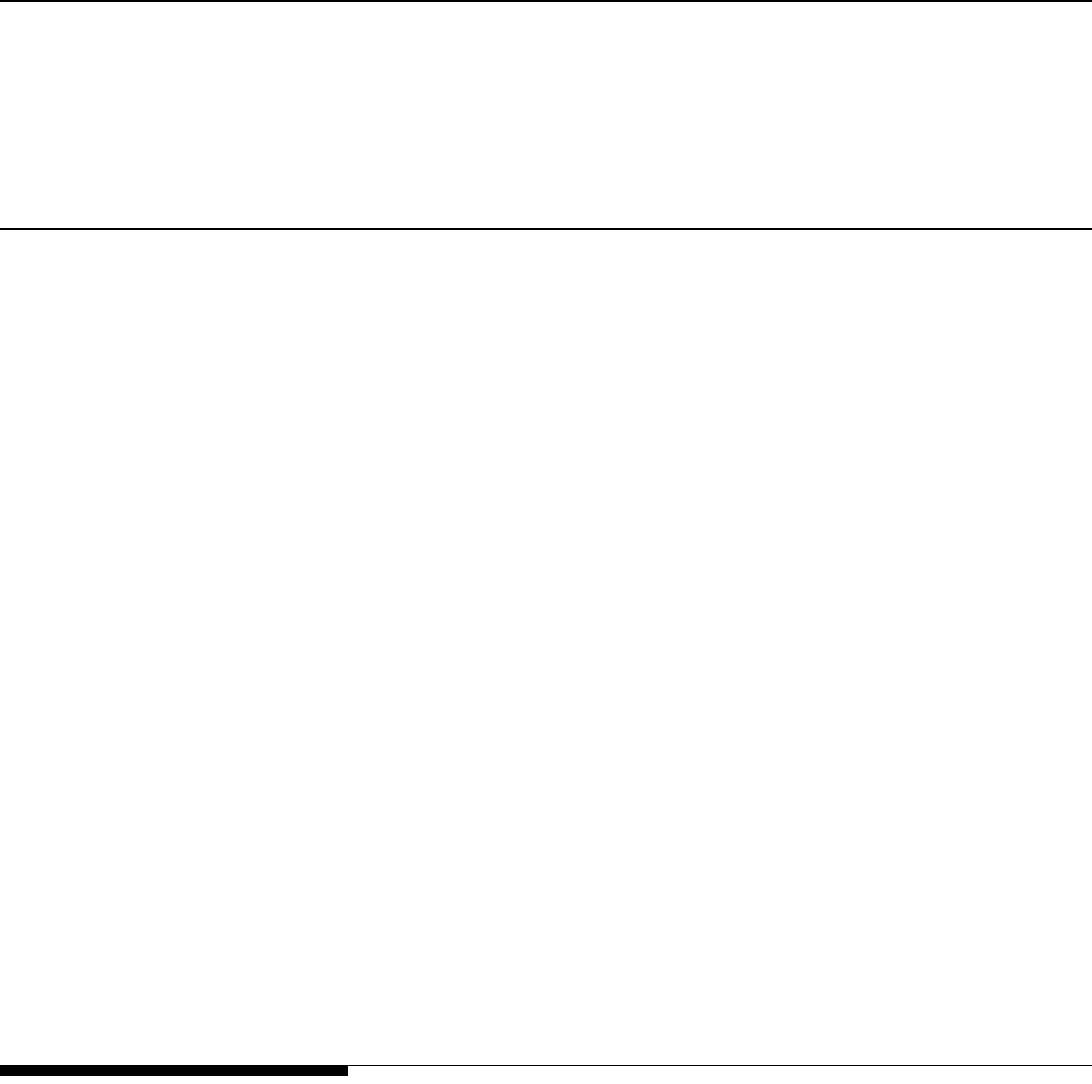

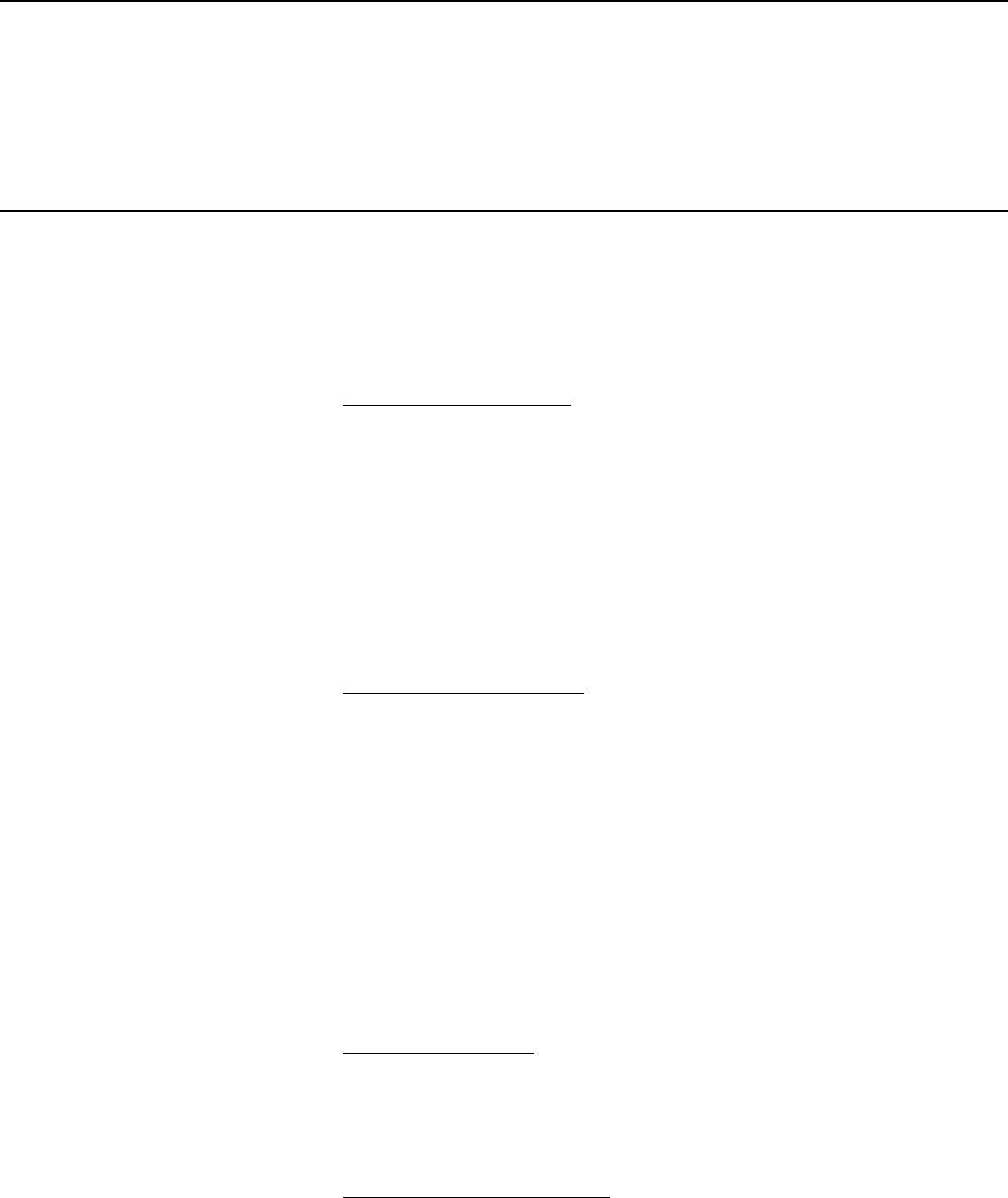

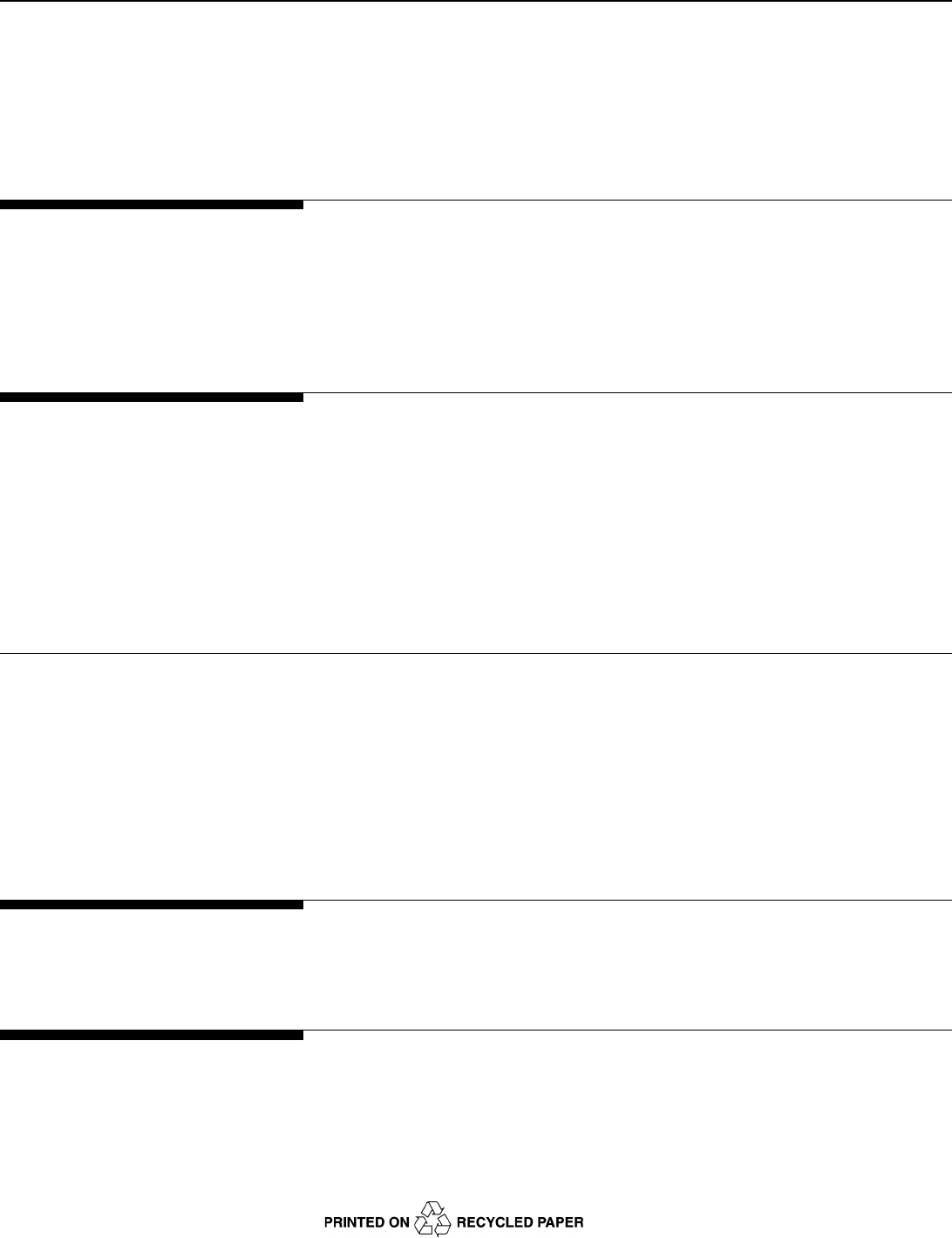

Since 1999, medical malpractice premium rates have increased dramatically

for physicians in some specialties in a number of states. However, among

larger insurers in the seven states GAO analyzed, both the premium rates

and the extent to which these rates have increased varied greatly (see

figure).

Multiple factors, including falling investment income and rising reinsurance

costs, have contributed to recent increases in premium rates in our sample

states. However, GAO found that losses on medical malpractice claims—

which make up the largest part of insurers’ costs—appear to be the primary

driver of rate increases in the long run. And while losses for the entire

industry have shown a persistent upward trend, insurers’ loss experiences

have varied dramatically across our sample states, resulting in wide

v

ariations in premium rates. In addition, factors other than losses can affect

p

remium rates in the short run, exacerbating cycles within the medical

malpractice market. For example, high investment income or adjustments

to account for lower than expected losses may legitimately permit insurers

to price insurance below the expected cost of paying claims. However,

because of the long lag between collecting premiums and paying claims,

underlying losses may be increasing while insurers are holding premium

rates down, requiring large premium rate hikes when the increasing trend in

losses is recognized. While these factors may explain some events in the

medical malpractice market, GAO could not fully analyze the composition

and causes of losses at the insurer level owing to a lack of comprehensive

data.

GAO’s analysis also showed that the medical malpractice market has

changed considerably since previous hard markets. Physician-owned and/or

operated insurers now cover around 60 percent of the market, self-insurance

has become more widespread, and states have passed laws designed to

reduce premium rates. As a result, it is not clear how premium rates might

behave during future soft or hard markets.

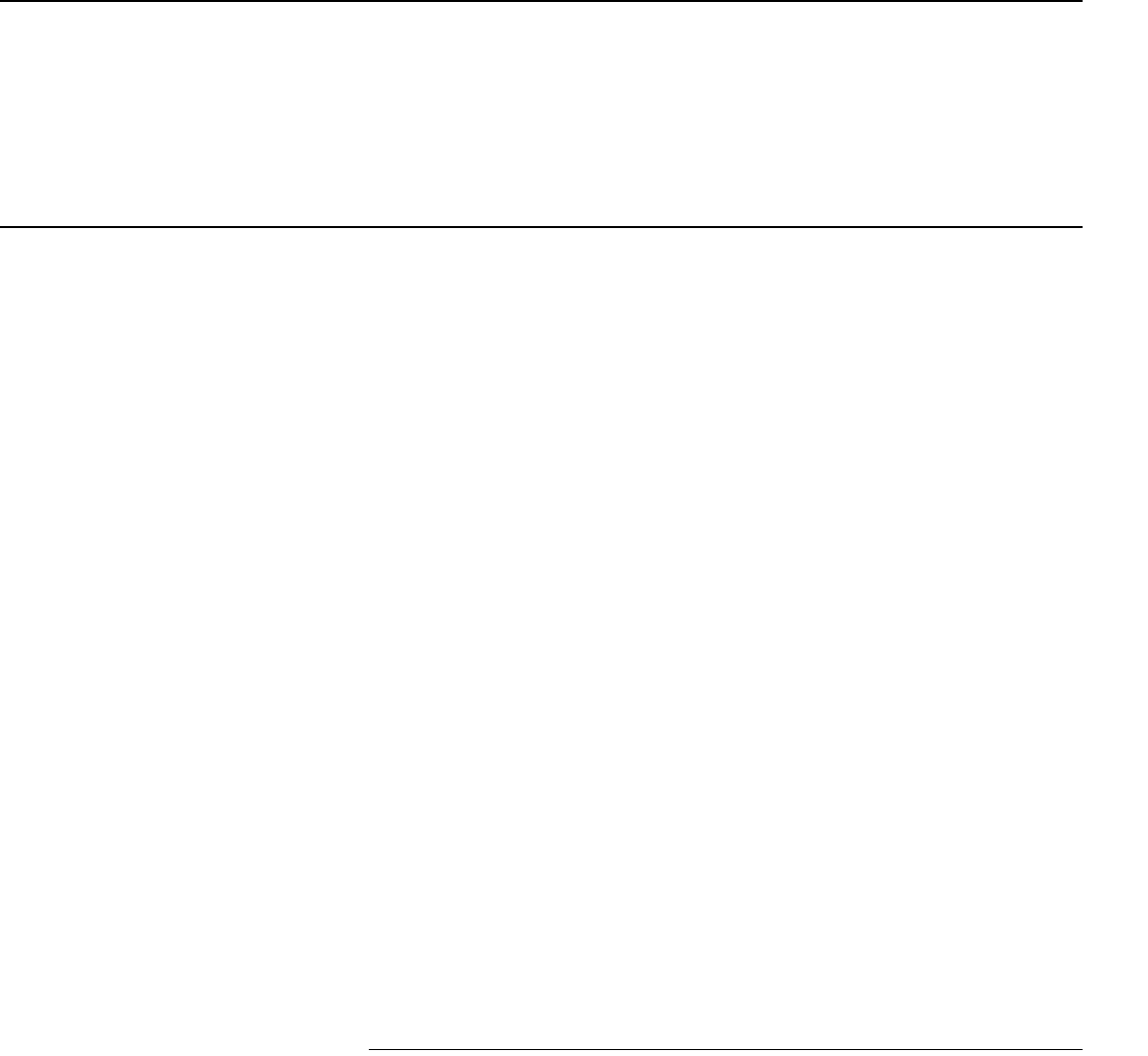

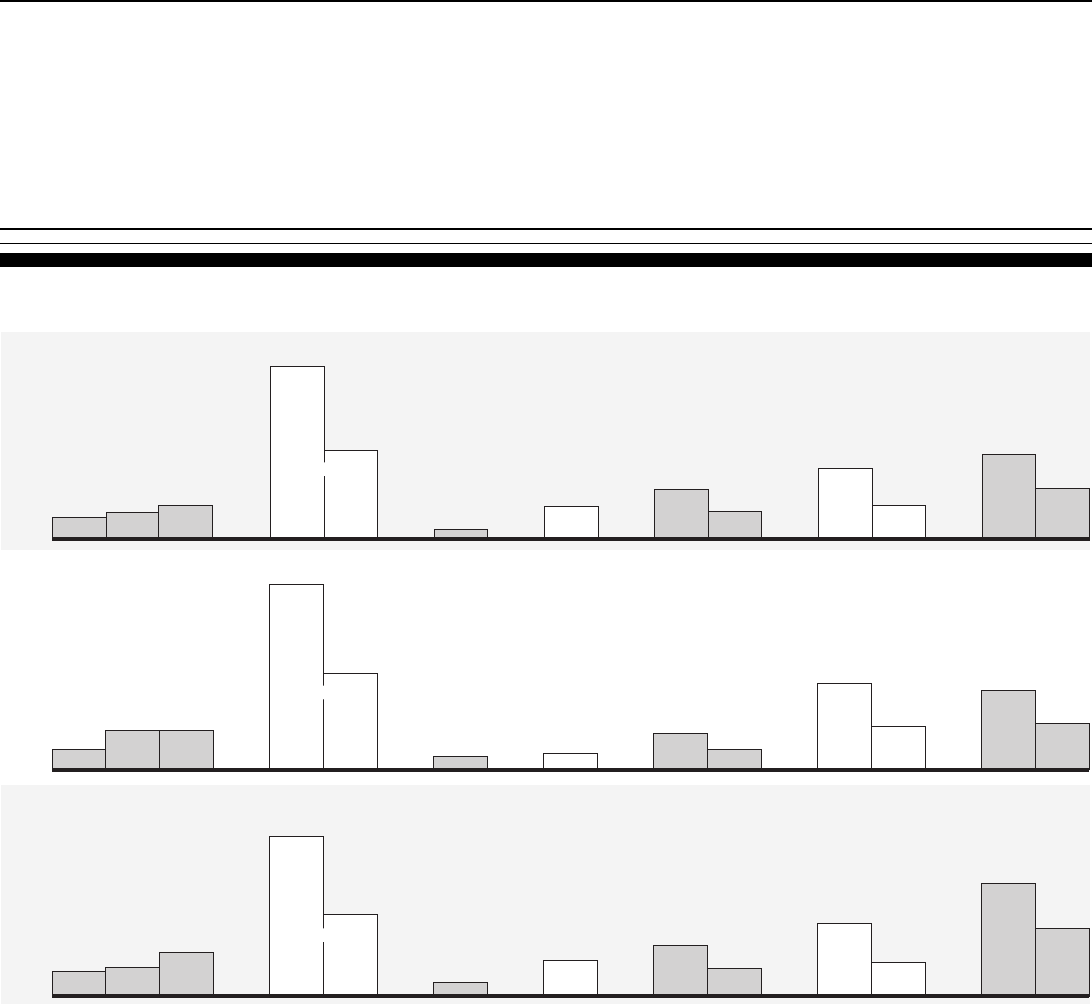

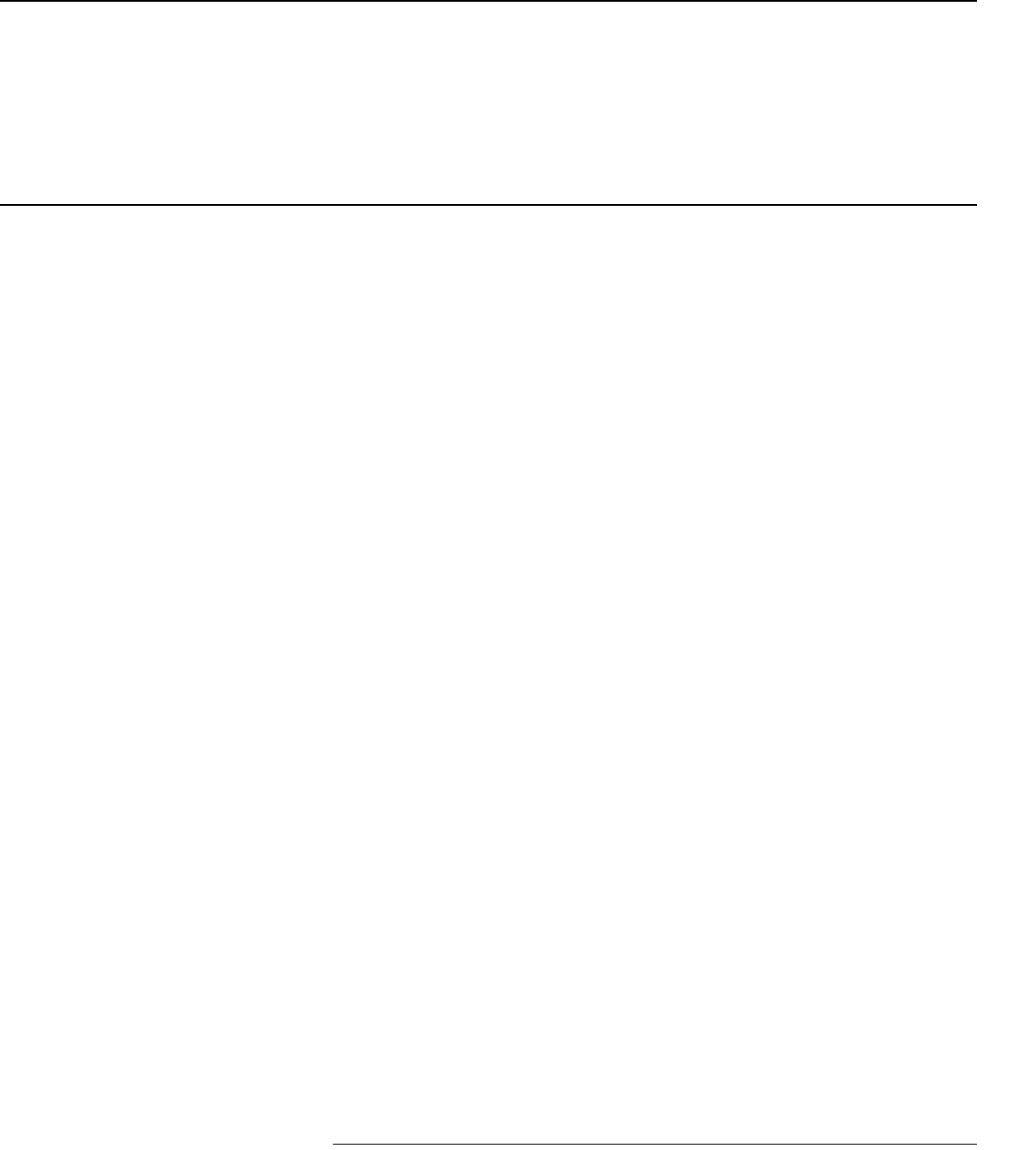

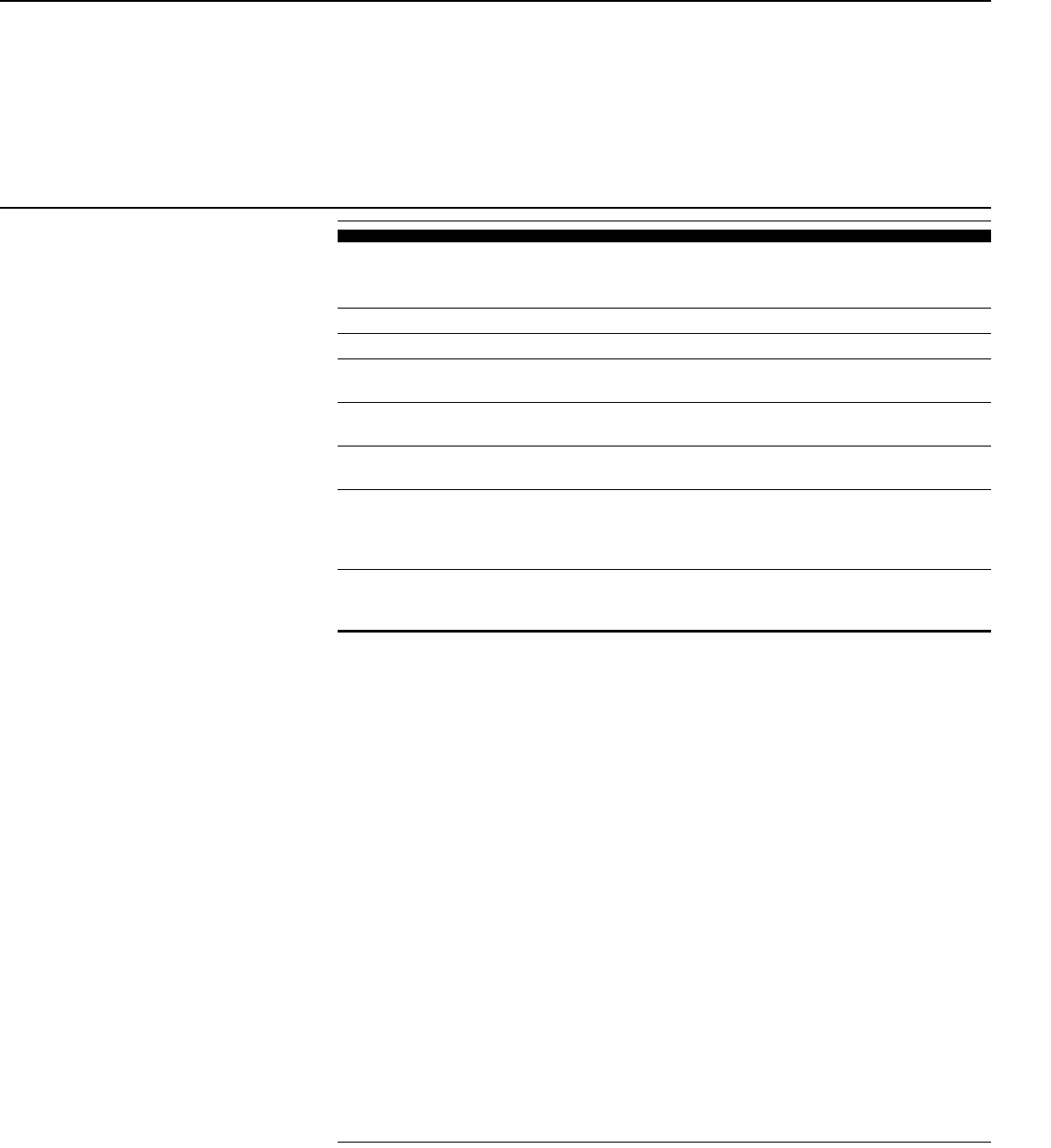

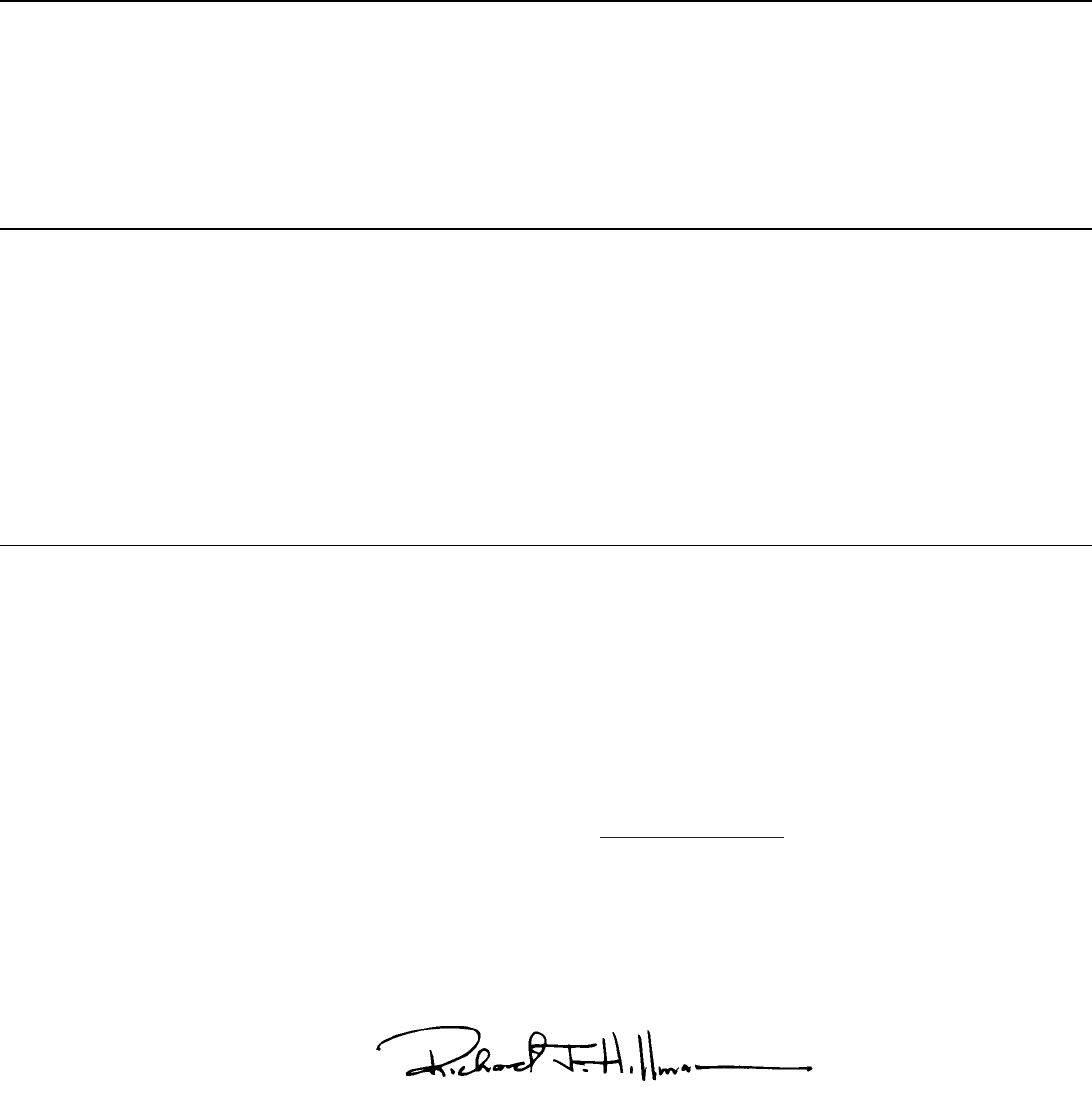

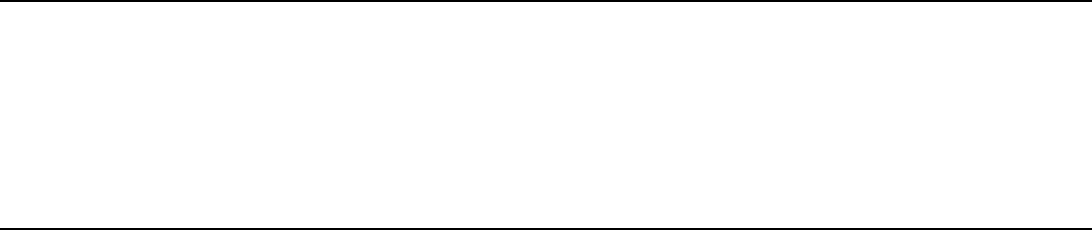

Medical Malpractice Premium Base Rates for Obstetricians and Gynecologists Quoted by

Larger Insurers in 1998 and 2002 in the Seven States GAO Visited (Dollars in Thousands)

Source: GAO analysis of annual surveys by the Medical Liability Monitor.

PMSLIC

(Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania)

TMLT

(El Paso,

Texas)

MIEC

(Clark

County,

Nevada)

MMIC

(Minnesota)

MACM

(Mississippi)

FPIC

(Dade

County,

Florida)

FPIC

(rest of

Florida)

Doctor's

Company

(northern

California)

0

50

100

150

200

250

34

31

140

201

76

103

18

17

37

45

95

142

29

64

58

92

1998 2002

Over the past several years, large

increases in medical malpractice

insurance premium rates have

raised concerns that physicians will

no longer be able to afford

malpractice insurance and will be

forced to curtail or discontinue

providing certain services.

Additionally, a lack of profitability

has led some large insurers to stop

selling medical malpractice

insurance, furthering concerns that

physicians will not be able to

obtain coverage. To help Congress

better understand the reasons

behind the rate increases, GAO

undertook a study to (1) describe

the extent of the increases in

medical malpractice insurance

rates, (2) analyze the factors that

contributed to those increases, and

(3) identify changes in the medical

malpractice insurance market that

might make this period of rising

premium rates different from

previous such periods.

GAO is not recommending

executive action. However, to

further the understanding of

conditions in current and future

medical malpractice markets,

Congress may wish to consider

encouraging the National

Association of Insurance

Commissioners and state insurance

regulators to identify and collect

additional, mutually beneficial data

necessary for evaluating the

medical malpractice insurance

market.

www.gao.gov/cgi-bin/getrpt?GAO-03-702.

To view the full product, including the scope

and methodology, click on the link above.

For more information, contact Richard J.

Hillman at (202) 512-8678 or

Highlights of GAO-03-702, a report to

congressional requesters

June 2003

MEDICAL MALPRACTICE INSURANCE

Multiple Factors Have Contributed to

Increased Premium Rates

Page i GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

Contents

Letter 1

Results in Brief 3

Background 6

Both the Extent of Increases in Medical Malpractice Premium Rates

and the Rates Themselves Varied across Specialties and States 9

Multiple Factors Have Contributed to the Increases in Medical

Malpractice Premium Rates 15

The Medical Malpractice Insurance Market Has Changed since

Previous Hard Markets 37

Conclusions 43

Matter for Congressional Consideration 46

NAIC Comments and Our Evaluation 46

Appendixes

Appendix I: Scope and Methodology 49

Appendix II: Legal Summary 51

Appendix III: State Summaries 55

Market Description 55

Insurer Characteristics and Market Share 56

Rate Regulation 56

State Tort Laws 57

Appendix IV: GAO Contacts and Staff Acknowledgments 66

GAO Contacts 66

Acknowledgments 66

Related GAO Products

67

Tables

Table 1: Annual Yields for Selected Bonds, 1995–2002, and Average

Return on Investment Assets, 1997–2002, for the 15 Largest

Writers of Medical Malpractice Insurance in 2001 25

Table 2: Hypothetical Example of How Premium Rates Change

When the Return on Investments Falls 27

Figures

Figure 1: Premium Base Rates of the Largest Insurers in Seven

Selected States for Three Medical Specialties,

1992–2002 11

Contents

Page ii GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

Figure 2: Percentage Changes in Premium Base Rates of the

Largest Medical Malpractice Insurers in Seven Selected

States for Three Medical Specialties, 1999–2002 12

Figure 3: 2002 Medical Malpractice Insurance Premium Base Rates

of the Largest Insurers in Seven Selected States for Three

Medical Specialties 14

Figure 4: Inflation-Adjusted Paid and Incurred Losses for the

National Medical Malpractice Insurance Market, 1975–

2001 (Using the CPI, in 2001 Dollars) 17

Figure 5: Inflation-Adjusted Aggregate Paid Losses for Medical

Malpractice Insurers in Seven Selected States, 1975-2001

(Using the CPI, in 2001 Dollars) 19

Figure 6: Inflation-Adjusted Aggregate Incurred Losses for Medical

Malpractice Insurers in Seven Selected States, 1975-2001

(Using the CPI, in 2001 Dollars) 21

Figure 7: Net Profit or Loss as a Percentage of Net Worth for

Medical Malpractice Insurance Companies Nationwide,

1990–2001 29

Figure 8: Aggregate Incurred Losses as a Percentage of Premiums

Earned for Medical Malpractice Insurers in Seven

Selected States, 1975–2001 30

Figure 9: Incurred Losses as a Percentage of Premium Income for

Medical Malpractice Insurers and Property-Casualty

Insurers Nationwide, 1976–2001 34

Figure 10: California 59

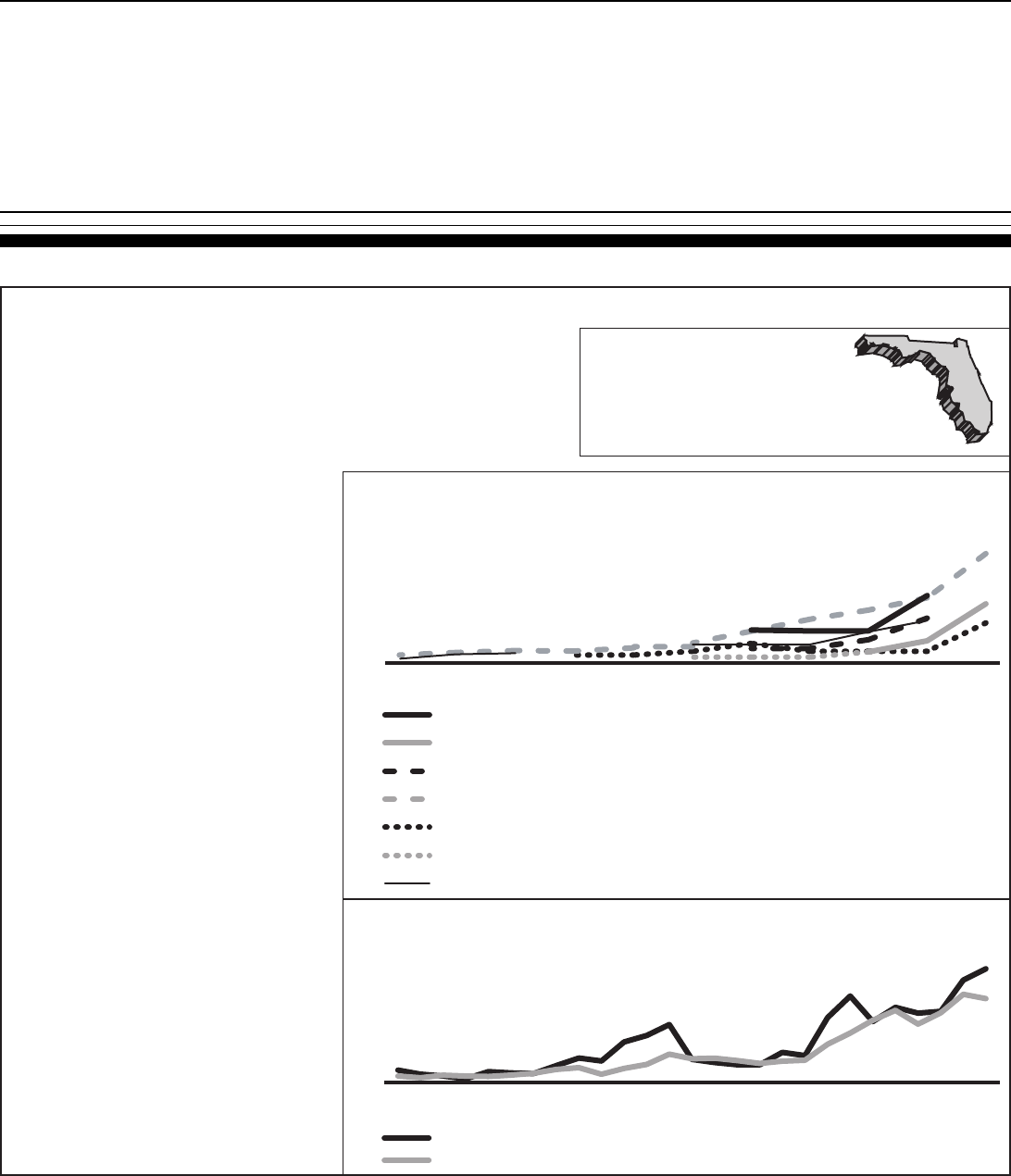

Figure 11: Florida 60

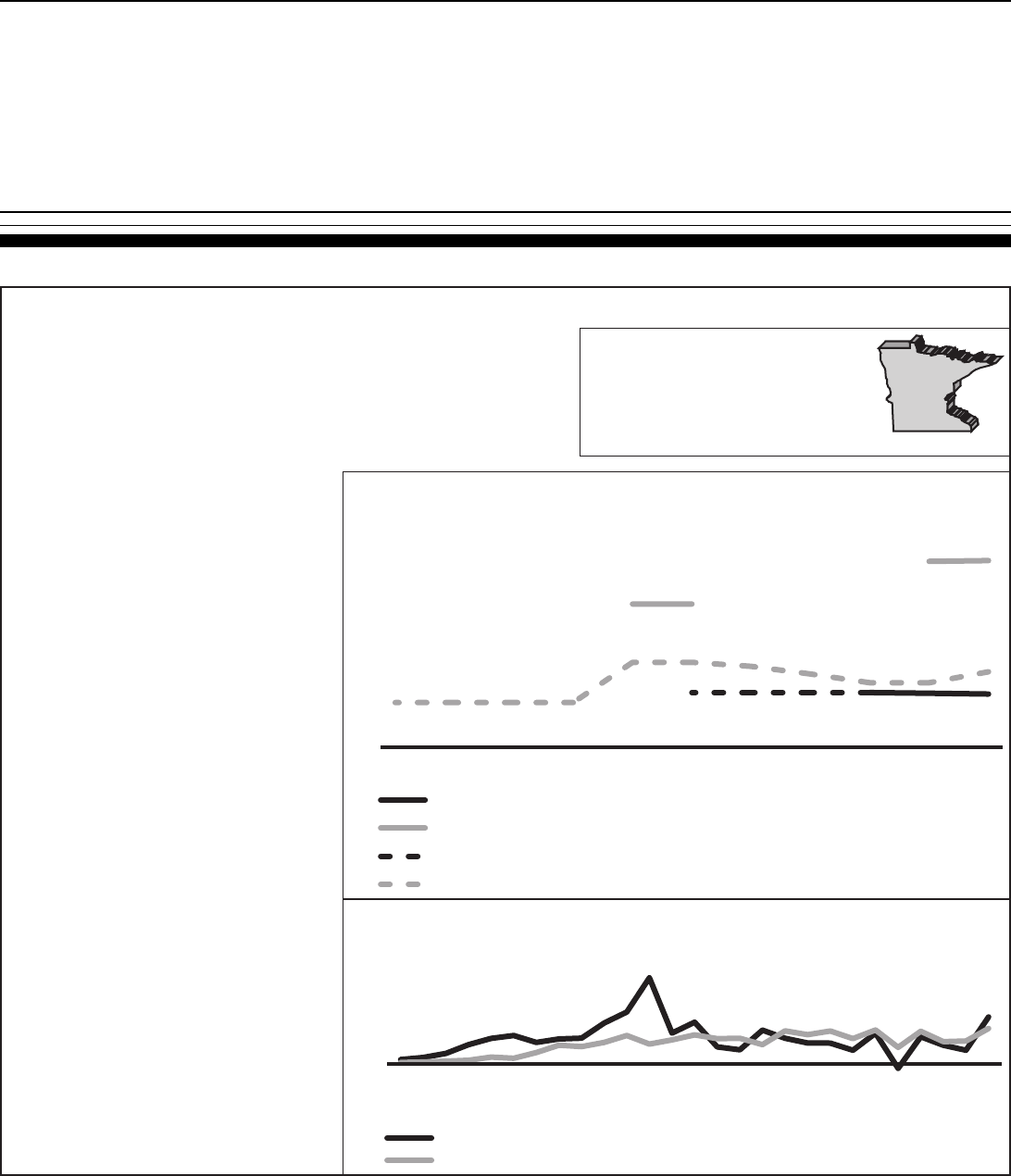

Figure 12: Minnesota 61

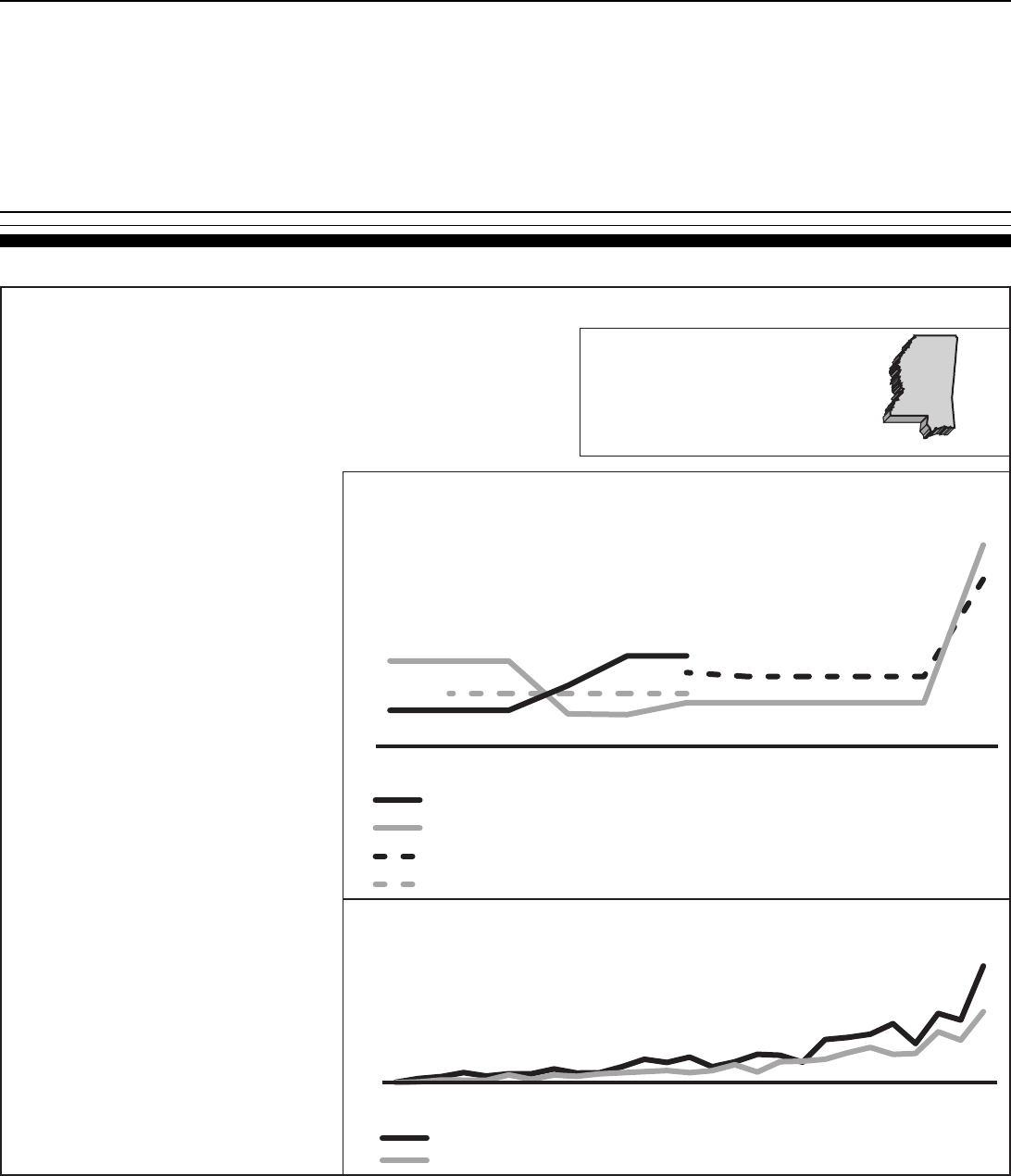

Figure 13: Mississippi 62

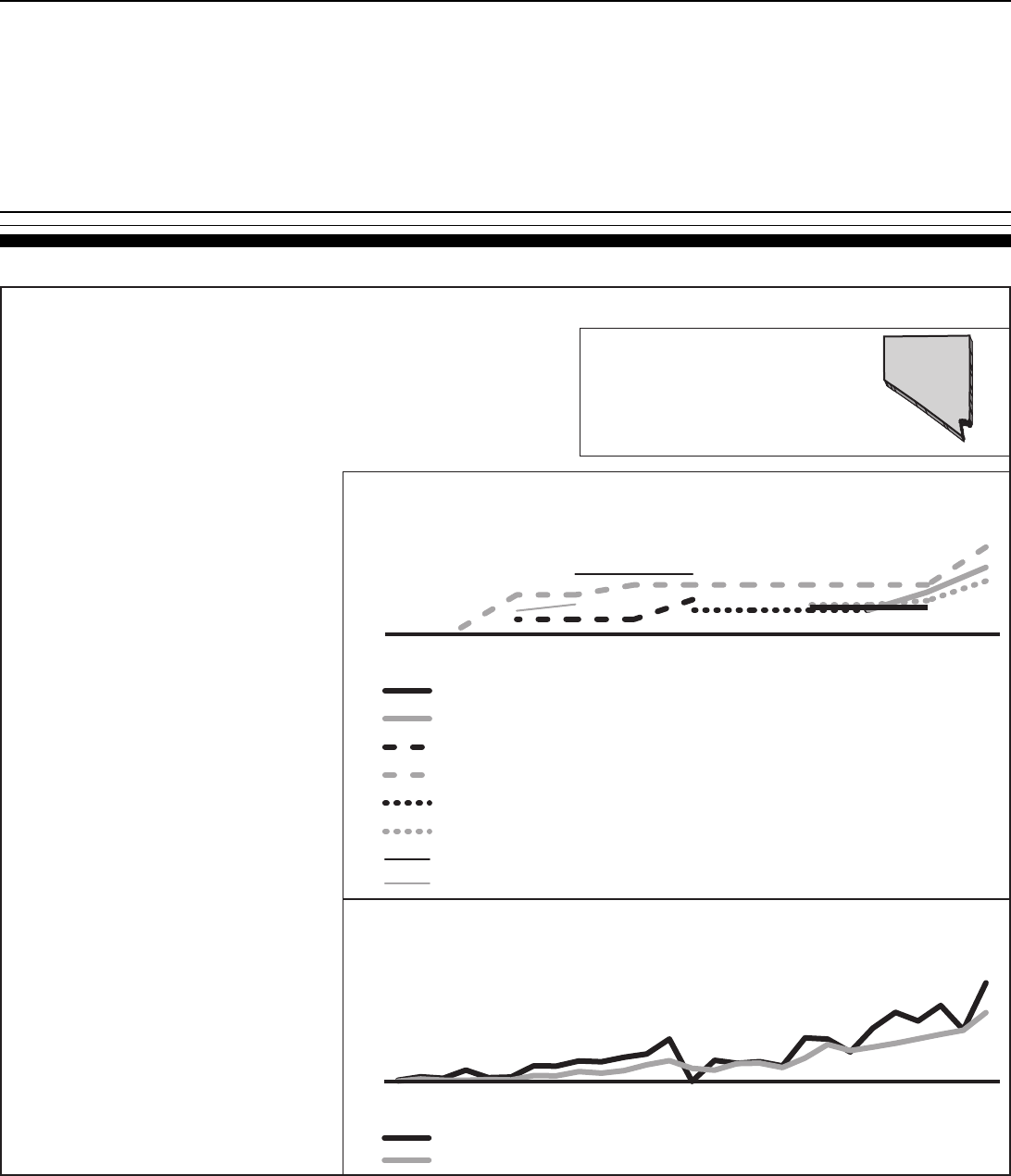

Figure 14: Nevada 63

Figure 15: Pennsylvania 64

Figure 16: Texas 65

Contents

Page iii GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

Abbreviations

AMA American Medical Association

CAP/MPT Cooperative of American Physicians/

Mutual Protection Trust

CDI California Department of Insurance

CPI Consumer Price Index

DOI Department of Insurance

FMA Florida Medical Association

FPIC First Professionals Insurance Company

JUA Joint Underwriting Association

MACM Medical Assurance Company of Mississippi

MIEC Medical Insurance Exchange of California

MIIX Medical Inter-Insurance Exchange

MLM Medical Liability Monitor

MMIC Midwest Medical Insurance Company

NAIC National Association of Insurance Commissioners

NMIC Nevada Mutual Insurance Company

NSCL National Conference of State Legislatures

PIAA Physician Insurers Association of America

PID Pennsylvania Insurance Department

PMSLIC Pennsylvania Medical Society Liability Insurance

Company

SCPIE Southern California Physicians Insurance Exchange

TMA Texas Medical Association

TMLT Texas Medical Liability Trust

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. It may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further

permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or

other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to

reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

United States General Accounting Office

Washington, D.C. 20548

Page 1 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

A

June 27, 2003 Letter

Congressional Requesters

Since the late 1990s, premium rates for medical malpractice insurance have

increased dramatically for physicians in certain specialties and states.

1

These increases have raised concerns that many physicians will no longer

be able to afford malpractice insurance and may be forced to curtail or

discontinue providing services. These concerns have been heightened as

some large insurers, faced with declining profits, have either stopped

selling medical malpractice insurance or reduced their operations in a

number of states. But disagreement exists over the causes of increased

premium rates and what, if anything, should be done in response to the

current situation. For example, some have argued for tort reform as a

means of lowering certain awards in medical malpractice lawsuits and

advocate legislative changes at the state level designed to place a cap on

such awards. Others have argued for medical reforms as a means of

reducing the incidence of medical malpractice or for insurance reforms as

a way to moderate premium rate increases.

In response to these concerns, you asked us to determine the reasons

behind the recent increases in some medical malpractice insurance rates.

2

Our specific objectives were to (1) describe the extent of the increases in

medical malpractice insurance rates, (2) analyze the factors that have

contributed to the increases, and (3) identify changes in the medical

malpractice insurance market that may make the current period of rising

premium rates different from earlier periods of rate hikes. We will also

1

Medical malpractice lawsuits are generally based on tort law, which includes both statutes

and court decisions. A tort is a wrongful act or omission by an individual that causes harm

to another individual. Typically, a malpractice tort would be based on the claim that the

health care provider was negligent, had failed to meet the acceptable standard of care owed

to the patient, and thus had caused injury to the patient.

2

Some health care provider associations and others have expressed concern over medical

malpractice insurance premium rates for nursing homes and hospitals, but this topic is

outside the scope of our report.

Page 2 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

issue a related report that describes the effect of rising malpractice

premiums on access to health care and related issues.

3

Recognizing that the medical malpractice market can vary considerably

across states, as part of our review we judgmentally selected a sample of

seven states—California, Florida, Minnesota, Mississippi, Nevada,

Pennsylvania, and Texas—in order to conduct a more in depth review in

each of those states. Our sample contains a mix of states based on the

following characteristics: extent of any recent increases in premium rates,

status as a “crisis state” according to the American Medical Association,

presence of caps on noneconomic damages, state population, and

aggregate loss ratios for medical malpractice insurers within the state.

Except where noted otherwise, our analyses were limited to these states.

Within each state, we spoke to one or both of the two largest and currently

active medical malpractice insurers,

4

the state insurance regulator, and the

state association of trial attorneys. In six states, we spoke to the state

medical association, and in five states, we spoke to the state hospital

association. To examine the extent of increases in medical malpractice

insurance rates in our sample states, we reviewed annual survey data

collected by a private company.

5

To analyze the factors contributing to the

premium rate increases in our sample states as well as nationally, we

reviewed data provided by medical malpractice insurers to state insurance

regulators, the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC),

6

3

For other related GAO products, see the list at the end of this report.

4

We determined the largest insurers in 2002 based on premiums written for calendar year

2001.

5

The Medical Liability Monitor annually surveys providers of medical malpractice

insurance to obtain their premium base rates for three different specialties: internal

medicine, general surgery, and obstetrics/gynecology.

6

NAIC is a voluntary association of the heads of each state insurance department, the

District of Columbia, and four U.S. territories. NAIC assists state insurance regulators by

providing guidance, model (or recommended) laws and guidelines, and information-sharing

tools.

Page 3 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

and A.M. Best

7

on insurers within our sample states as well as the 15 largest

writers of medical malpractice insurance nationally in 2001 (whose

combined market share nationally was approximately 64.3 percent). We

also spoke with officials from professional actuarial and insurance

organizations and national trial attorney and medical associations and

reviewed their testimonies before Congress. In addition, we analyzed data

on medical malpractice claims collected by insurers, state regulators, and

others in our sample states as well as nationally.

To analyze how the national medical malpractice insurance market has

changed since previous periods of rising premium rates, we reviewed

studies published by NAIC, reviewed state insurance regulations and tort

laws, and spoke to the insurers and state insurance departments in our

sample states. We also spoke to officials from national professional

actuarial, legal, and insurance organizations. Appendix I contains a more

detailed description of our methodology.

Results in Brief

Since 1999, medical malpractice premium rates

for physicians in some

states have increased dramatically. Among the seven states that we

analyzed, we found that both the extent of the increases and the premium

levels varied greatly not only from state to state but across medical

specialties and even among areas within states. For example, the largest

writer of medical malpractice insurance in Florida increased premium

rates for general surgeons in Dade County by approximately 75 percent

from 1999 to 2002, while the largest insurer in Minnesota increased

premium rates for the same specialty by about 2 percent over the same

period. The resulting 2002 premium rate quoted by the insurer in Florida

was $174,300 a year, more than 17 times the $10,140 premium rate quoted

by the insurer in Minnesota. In addition, the Florida insurer quoted a rate

for general surgeons outside Dade County of $89,000 a year for the same

coverage, approximately 51 percent of the rate it quoted inside Dade

County.

7

A.M. Best is a rating agency that provides current or prospective investors, creditors, and

policyholders with independent analyses of insurance companies’ overall financial strength,

creditworthiness, ability to pay claims, and company activities.

Page 4 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

Multiple factors have contributed to the recent increases in medical

malpractice premium rates in the seven states we analyzed. First, since

1998 insurers’ losses on medical malpractice claims have increased rapidly

in some states. For example, in Mississippi the amount insurers paid

annually on medical malpractice claims, or paid losses,

8

increased by

approximately 142 percent from 1998 to 2001 after adjusting for inflation.

9

We found that the increased losses appeared to be the greatest contributor

to increased premium rates, but a lack of comprehensive data at the

national and state levels on insurers’ medical malpractice claims and the

associated losses prevented us from fully analyzing the composition and

causes of those losses. For example, data that would have allowed us to

analyze claim severity at the insurer level on a state-by-state basis or

determine how losses were broken down between economic and

noneconomic damages were unavailable. Second, from 1998 through 2001

medical malpractice insurers experienced decreases in their investment

income

10

as interest rates fell on the bonds that generally make up around

80 percent of these insurers’ investment portfolios. While almost no

medical malpractice insurers experienced net losses on their investment

portfolios over this period, a decrease in investment income meant that

income from insurance premiums had to cover a larger share of insurers’

costs. Third, during the 1990s insurers competed vigorously for medical

malpractice business, and several factors, including high investment

returns, permitted them to offer prices that in hindsight, for some insurers,

did not completely cover their ultimate losses on that business. As a result

of this, some companies became insolvent or voluntarily left the market,

reducing the downward competitive pressure on premium rates that had

existed through the 1990s. Fourth, beginning in 2001 reinsurance rates for

medical malpractice insurers also increased more rapidly than they had in

8

Paid losses are the cash payments insurers made in a given period, such as a calendar year,

on claims reported during both the current and previous years. Incurred losses include the

insurer’s expected costs for claims reported in that year and adjustments to the expected

costs for claims reported in earlier years. In Mississippi, insurers’ incurred losses increased

approximately 197.5 percent from 1998 to 2001, after adjusting for inflation.

9

We adjusted for inflation using the consumer price index (CPI). The CPI is a measure of the

average change over time in the prices consumers pay for a basket of goods and services.

This report uses the CPI-U, which is meant to reflect the spending patterns of urban

consumers and covers about 87 percent of the total U.S. population.

10

In general, state insurance regulators require insurers to reduce their requested premium

rates in line with expected investment income. That is, the higher the expected income from

investments, the more premium rates must be reduced.

Page 5 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

the past, raising insurers’ overall costs.

11

In combination, all of these

factors contribute to the movement of the medical malpractice insurance

market through cycles of hard and soft markets--similar to those

experienced by the property-casualty insurance market as a whole--during

which premium rates fluctuate.

12

Cycles in the medical malpractice market

tend to be more extreme than in other insurance markets because of the

longer period of time required to resolve medical malpractice claims, and

factors such as changes in investment income and reduced competition can

exacerbate the fluctuations.

While the medical malpractice insurance market as a whole had

experienced periods of rapidly increasing premium rates during previous

hard markets in the mid-1970s and mid-1980s, the market has changed

considerably since then. These changes are largely the result of actions

insurers, health care providers, and states have taken to address increasing

premium rates. Beginning in the 1970s and 1980s, insurers began selling

“claims-made” rather than “occurrence-based” policies,

13

enabling insurers

to better predict losses for a particular year. Also in the 1970s, physicians,

facing increasing premium rates and the departure of some insurers, began

to form mutual nonprofit insurance companies. Such companies, which

may have some cost and other advantages over commercial insurers, now

comprise a significant portion of the medical malpractice insurance

market. More recently, an increasing number of large hospitals and groups

of hospitals or physicians have left the traditional commercial insurance

market and begun to insure themselves in a variety of ways—for example,

by self-insuring. While such arrangements can save money on

administrative costs, hospitals and physicians insured through these

arrangements assume greater financial responsibility for malpractice

claims than they would under traditional insurance arrangements and thus

may face a greater risk of insolvency. Finally, since periods of increasing

11

Reinsurance is insurance for insurance companies, which insurance companies routinely

use as a way to spread the risk associated with their insurance policies.

12

Some industry officials have characterized hard markets as periods of rapidly rising

premium rates, tightened underwriting standards, narrowed coverage, and the withdrawal

of insurers from certain markets. Soft markets are characterized by relatively flat or slow-

rising premium rates, less stringent underwriting standards, expanded coverage and strong

competition among insurers.

13

Claims-made policies cover claims reported during the year in which the policy is in effect.

Occurrence-based policies cover claims arising out of events that occurred but may not

have been reported during the year in which the policy was in effect. Most policies sold

today are claims-made policies.

Page 6 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

premium rates during the mid-1970s and mid-1980s, all states passed at

least some laws designed to reduce medical malpractice premium rates.

Some of these laws are designed to decrease insurers’ losses on medical

malpractice claims, while others are designed to more tightly control the

premium rates insurers can charge. These changes make it difficult to

predict how medical malpractice premiums might behave during future

hard and soft markets.

This report includes a matter that Congress may want to consider as it

looks for ways to improve the ability of Congress, state insurance

regulators, and others to analyze the current and future medical

malpractice insurance markets. Specifically, Congress may want to

consider encouraging NAIC and state insurance regulators to identify and

collect additional data necessary to evaluate the frequency,

14

severity,

15

and

causes of losses on medical malpractice claims.

We received comments on a draft of this report from NAIC’s Director of

Research. The Director generally agreed with the report’s findings and

matters for congressional consideration, and provided technical comments

that we have incorporated as appropriate. The Director’s comments are

discussed in greater detail at the end of this letter.

Background

Nearly all health care providers, such as physicians and hospitals, purchase

insurance that covers expenses related to medical malpractice claims,

including payments to claimants and legal expenses. The most common

physician policies provide $1 million of coverage per incident and

$3 million of coverage per year. Today the primary sellers of physician

medical malpractice insurance are the physician-owned and/or operated

insurance companies that, according to the Physician Insurers Association

of America, insure approximately 60 percent of all physicians in private

practice in the United States. Other health care providers may obtain

coverage through commercial insurance companies, mutual coverage

arrangements, or state-run insurance programs, or may self-insure (take

responsibility for claims themselves). Most medical malpractice insurance

policies offer claims-made coverage, which covers claims reported during

14

Claim frequency is the number of claims per exposure unit, such as a single general

practitioner.

15

Claim severity is the average loss per claim.

Page 7 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

the year in which the policy is in effect. A small and declining number of

policies offer occurrence coverage, which covers all claims arising out of

events that occurred during the year in which the policy was in effect.

Medical malpractice insurance operates much like other types of

insurance, with insurers collecting premiums from policyholders in

exchange for an agreement to defend and pay future claims within the

limits set by the policy. Insurers invest the premiums they collect and use

the income from those investments to reduce the amount of premium

income that would have been required otherwise. Claims against a

policyholder are recorded as expenses, or incurred losses, which are equal

to the amount paid on those claims as well as the insurer’s estimate of

future losses on those same claims. The liability associated with the

portion of these incurred losses that have not yet been paid by the insurer

is collectively known as the insurer’s loss reserve. In order to maintain

financial soundness, insurers must maintain assets in excess of total

liabilities—including loss reserves and reserves for premiums received but

not yet earned

16

—to make up what is known as the insurer’s surplus. State

insurance departments monitor insurers’ solvency by tracking, among

other measures, the ratio of total annual premiums to this surplus. Medical

malpractice insurers generally attempt to keep their surplus approximately

equal to their annual premium income.

Medical malpractice insurers establish premium base rates for particular

medical specialties within a state and sometimes for particular geographic

regions within a state. Insurers may also offer discounts or add surcharges

for the particular characteristics of policyholders, such as claim histories

or whether they participate in risk-management programs. The premium

rates are based on anticipated losses on claims and related expenses,

expected investment income, the need to build a surplus, and, for for-profit

insurers, the desire to earn a reasonable profit for shareholders. In most

states the insurance regulators have the authority to approve or deny

proposed changes to premium rates.

16

Insurers collect premiums in advance for coverage during a future period of time, and as

that period of time passes, those premiums are “earned.” Premiums related to periods of

time yet to pass are considered “unearned” and are a liability on the books of the insurer.

Page 8 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

For several reasons, accurately predicting losses on medical malpractice

claims is difficult. First, according to a national insurer association we

spoke with, most medical malpractice claims take an average of more than

5 years to resolve, including discovering the malpractice, filing a claim,

determining (through settlement or trial) payment responsibilities, if any,

and paying the claim.

17

In addition, some claims may not be resolved for as

long as 8 to 10 years. As a result, insurers often must estimate costs years in

advance. Second, the range of potential losses is wide. Actuaries we spoke

with told us that individual claims with similar characteristics can result in

very different losses for the insurer, making it difficult to predict the

ultimate cost of any single claim. Third, the predictive value of historical

data is further limited by the often small pool of relevant policyholders. For

example, a relevant pool of policyholders would be physicians practicing a

particular specialty within a specific state and perhaps within a specific

geographic area within that state. In smaller states, and for some of the less

common but more risky specialties, this pool could be very small and

provide only a limited amount of data that could be used to estimate future

costs.

Medical malpractice insurance is regulated by state insurance departments

and subject to state laws. That is, insurers selling medical malpractice

insurance in a particular state are subject to that state’s regulations for

their operations within that state, and all claims within that state are

subject to that state’s tort laws. Insurance regulations can vary across

states, creating differences in the way insurance rates are regulated. For

example, one state insurance regulator we spoke with essentially let the

insurance market determine appropriate rates, while another had an

increased level of review, including approving specific company rates on a

case-by-case basis. NAIC assists state insurance regulators in developing

these regulations by providing guidance, model (or recommended) laws

and guidelines, and information-sharing tools.

In response to concerns over rising premium rates, physicians, medical

associations, and insurers have pushed for state and federal legislation that

would, among other things, limit the amount of damages paid out on

medical malpractice claims. A few states have passed legislation with such

limitations over the past several years, and federal legislation is pending.

On March 13, 2003, the House of Representatives passed the Help Efficient,

17

Estimates of some individual insurers we spoke with ranged from around 3 years to over

5 years.

Page 9 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

Accessible Low-Cost, Timely Healthcare (HEALTH) Act of 2003, which

includes, among other things, a limit on certain types of damages in

medical malpractice claims. On March 12, 2003, a similar bill of the same

name was introduced in the Senate, but as of June 2003, no additional

action had been taken.

Both the Extent of

Increases in Medical

Malpractice Premium

Rates and the Rates

Themselves Varied

across Specialties and

States

Beginning in 1999 and 2000, medical malpractice insurers in our seven

sample states increased their premium rates

18

for the physician specialties

of general surgery, internal medicine, and obstetrics/gynecology faster than

they had since at least 1992. These specialties were the only ones for which

data were available, and 1992 was the earliest year for which we could

obtain comprehensive survey data.

19

However, both the extent of these

changes and the level of the premium rates insurers charged varied greatly

across medical specialties, states, and even areas within states. From 1999

through 2002, one large insurer raised rates more for internal medicine

than for general surgery, while another raised rates 12 times more for

general surgery than for internal medicine. Changes in premium base rates

among some of the largest insurers in each state ranged from a reduction of

about 9 percent for obstetricians and gynecologists insured by one

California company to an increase of almost 170 percent for doctors in the

18

In this report, premium rates are the base rates insurers submit to state regulators along

with a schedule of potential deductions or additions related to the particular characteristics

of policyholders. The actual premium rate insurers charge individual policyholders varies

from the base rate. We could not determine the extent to which the actual premium rates

charged varied from the base rates, but among some of the insurers we spoke with, the

actual premium rates ranged from about 50 to 100 percent of the base rates over the past

several years. Some market observers and participants also told us that the discounts have

decreased over the last several years.

19

All premium rate information in this report is based on survey data collected by the

Medical Liability Monitor, a newsletter that, among other things, publishes the results of its

annual surveys of the premium rates of medical malpractice insurers. Comprehensive

survey data was available for years 1992 to 2002. The surveys, which are sent to medical

malpractice insurers, request premium rates for each state or smaller region for a standard

amount of coverage in three specialties—internal medicine, general surgery, and

obstetrics/gynecology. The Medical Liability Monitor selected these in order to have data

representative of low-, medium-, and high-risk specialties. In the survey results for 1999

through 2002, all 50 states were represented in the rate information that companies

provided. The premium rates collected in the survey are base rates that do not reflect the

discounts or the additional amounts insurers charge, so actual premium rates can vary from

the premium rates given in the survey.

Page 10 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

same specialty in one area of Pennsylvania.

20

At the same time, premium

rates for the same amount of coverage for the same medical specialty

varied by a factor of as much as 17 among states—that is, the rate in one

state was 17 times higher than the rate in a different state.

Premium Rates Have Grown

Rapidly since 1998 for

Certain Specialties in Some

States

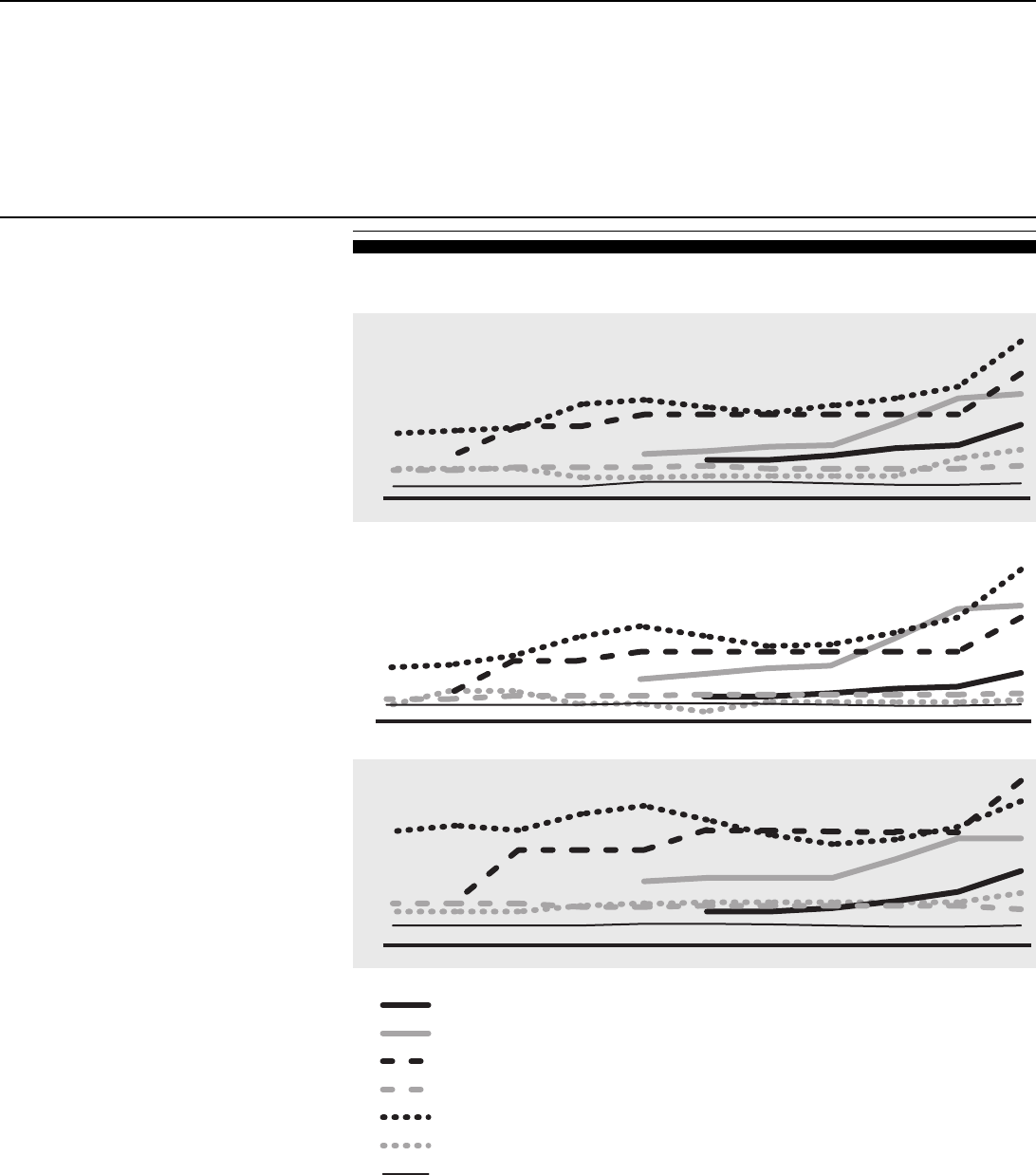

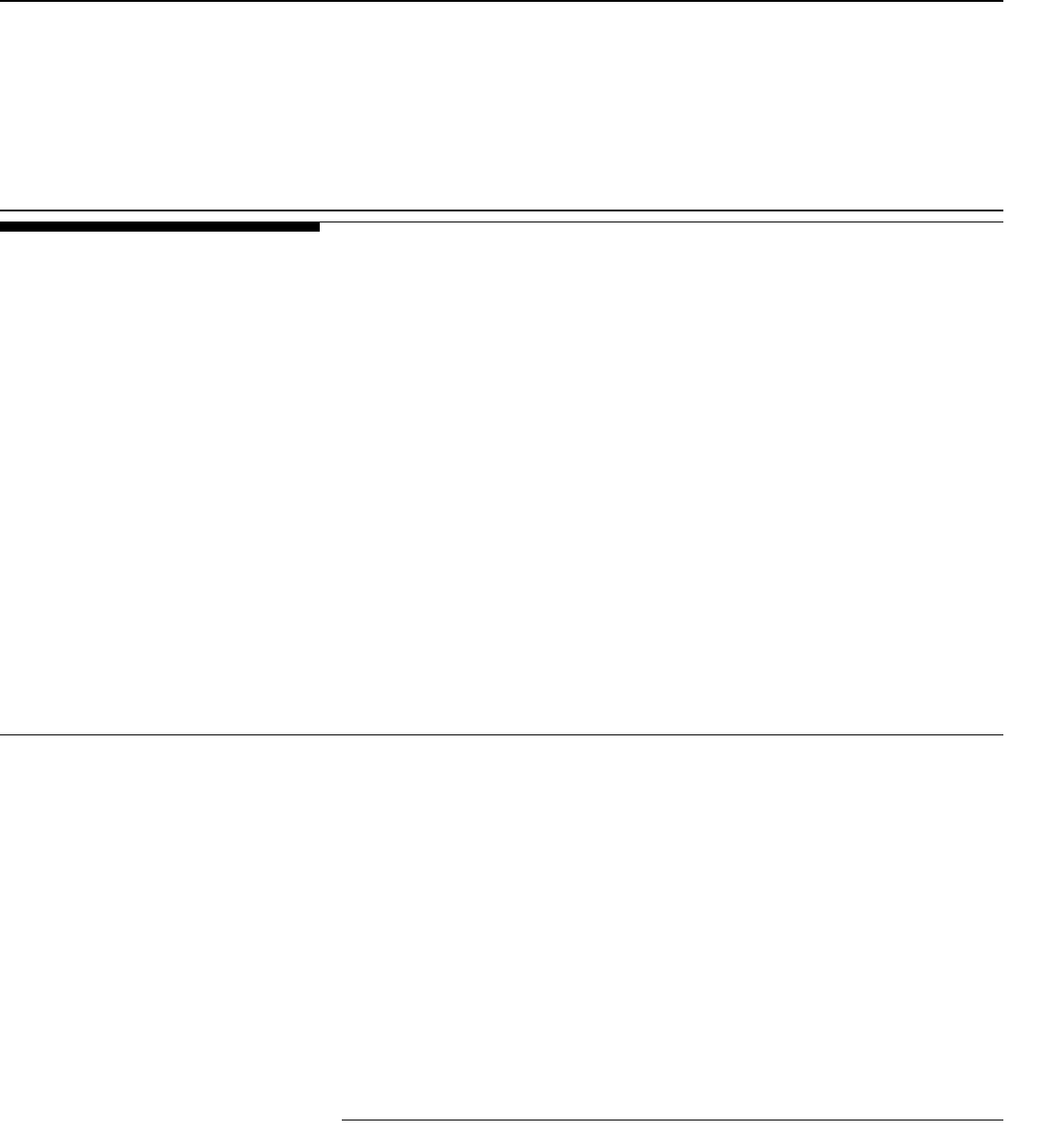

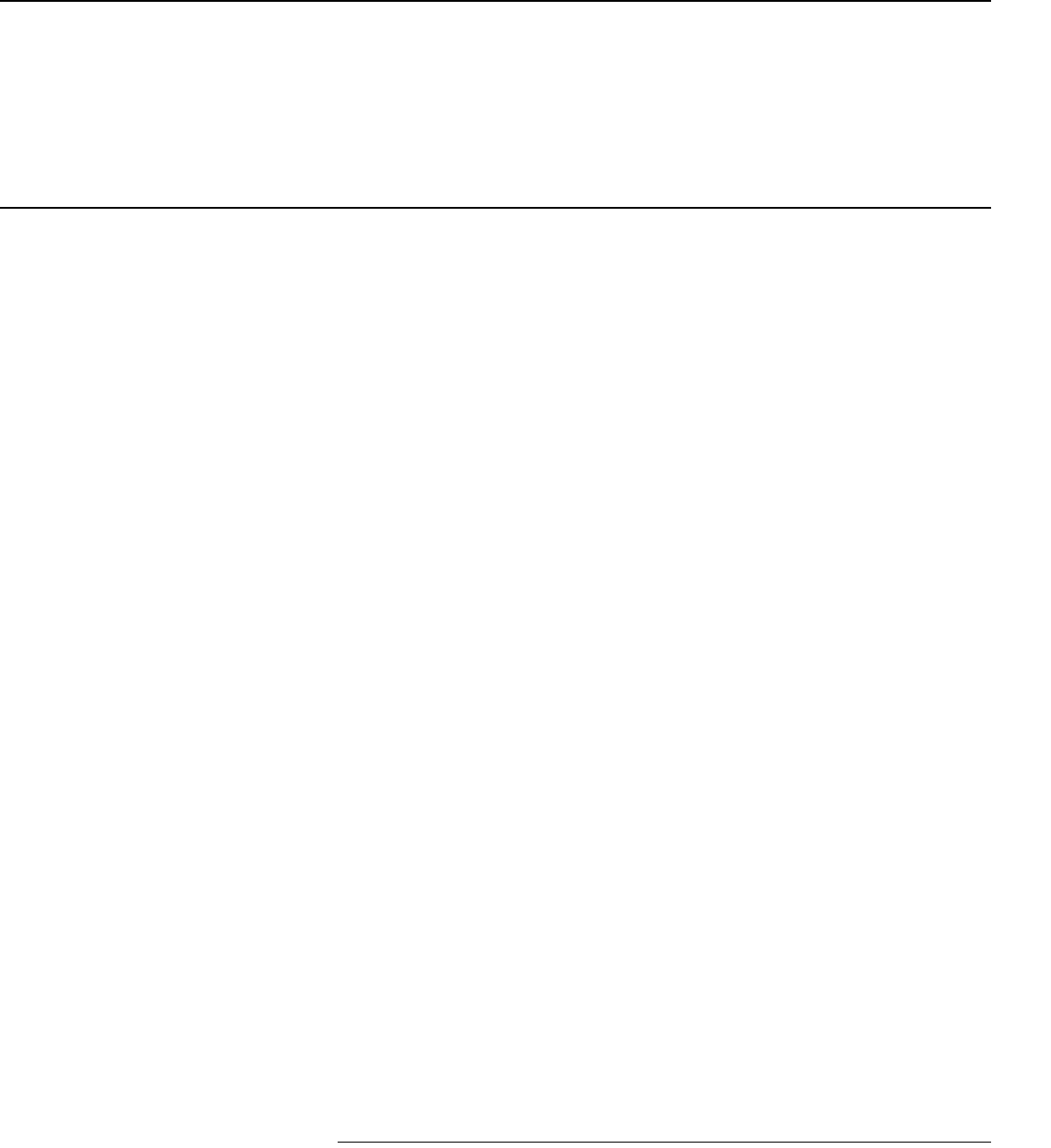

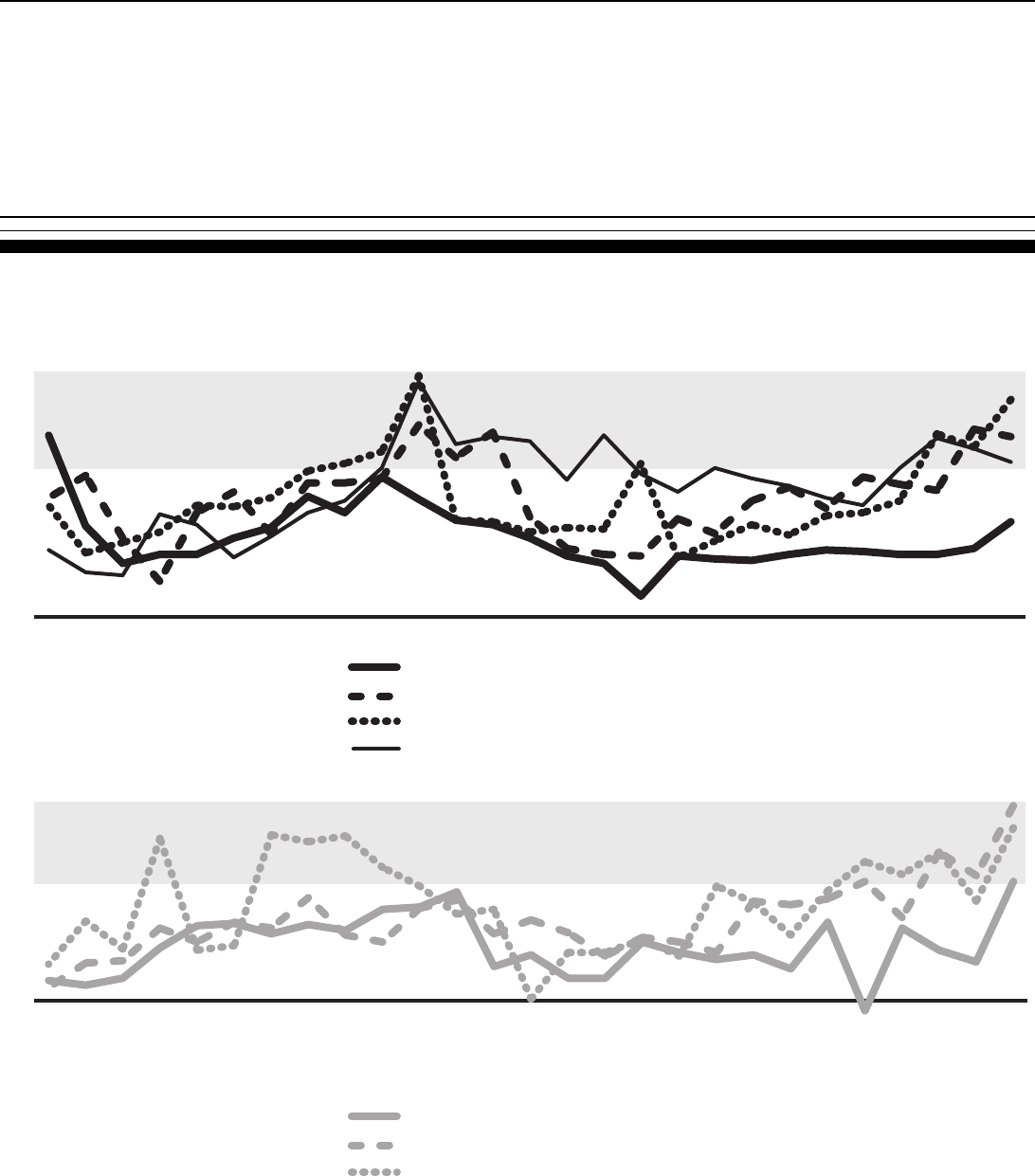

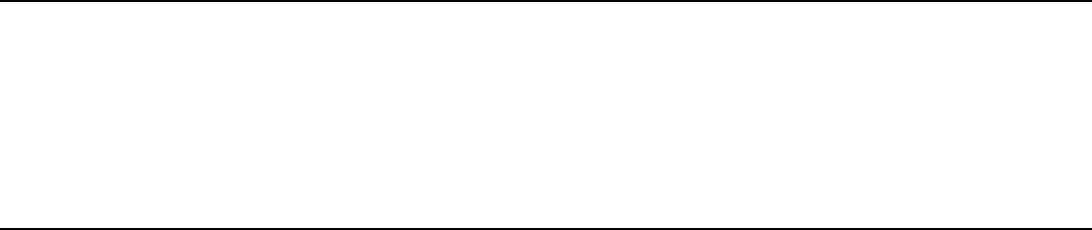

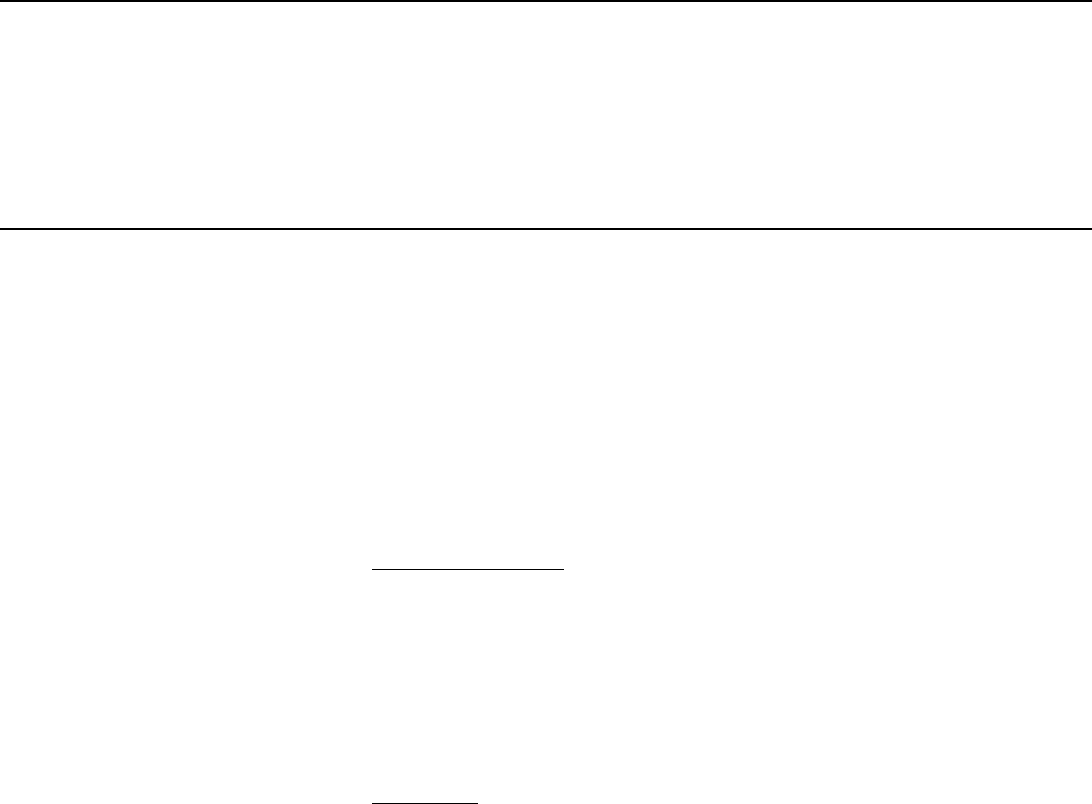

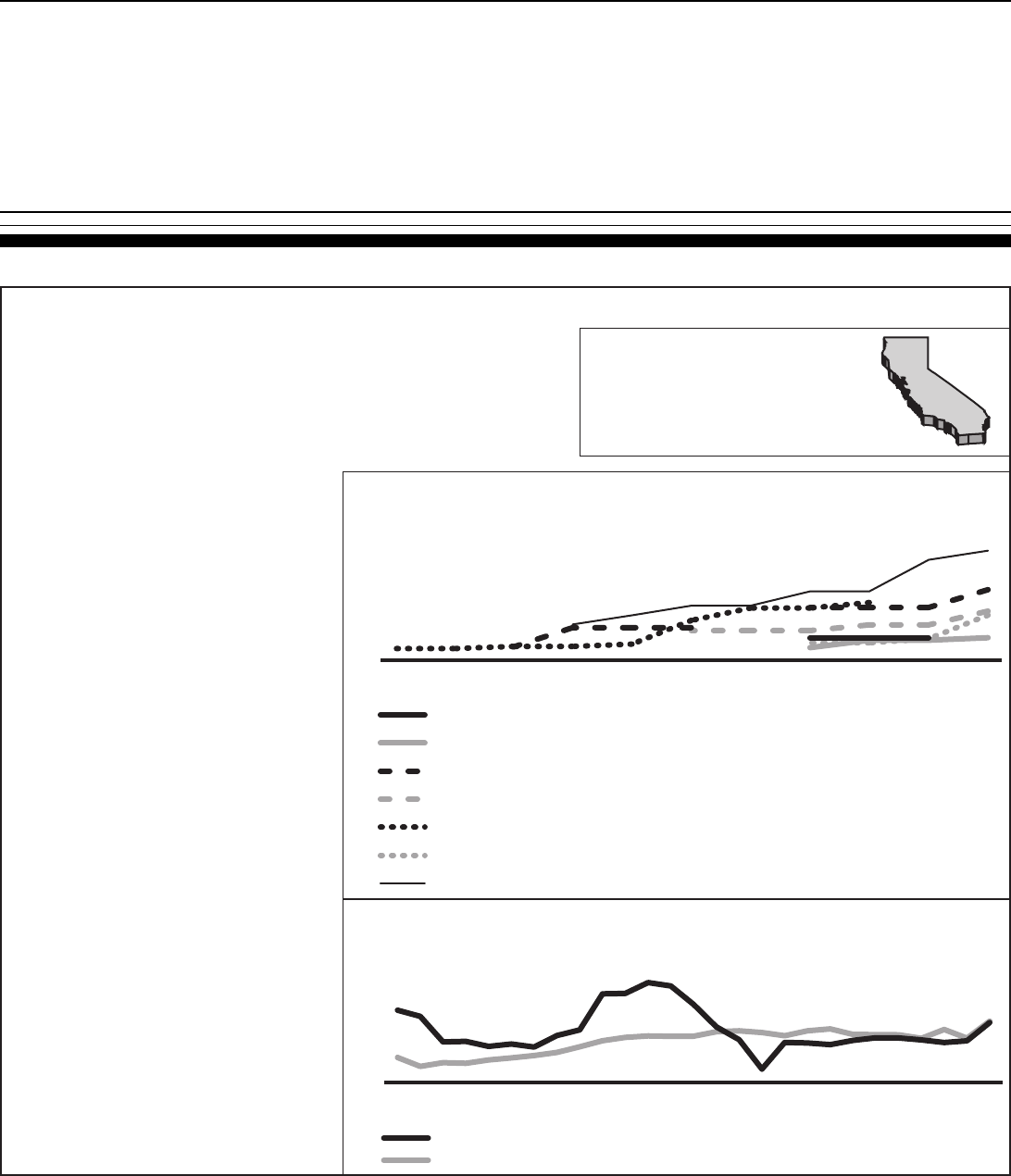

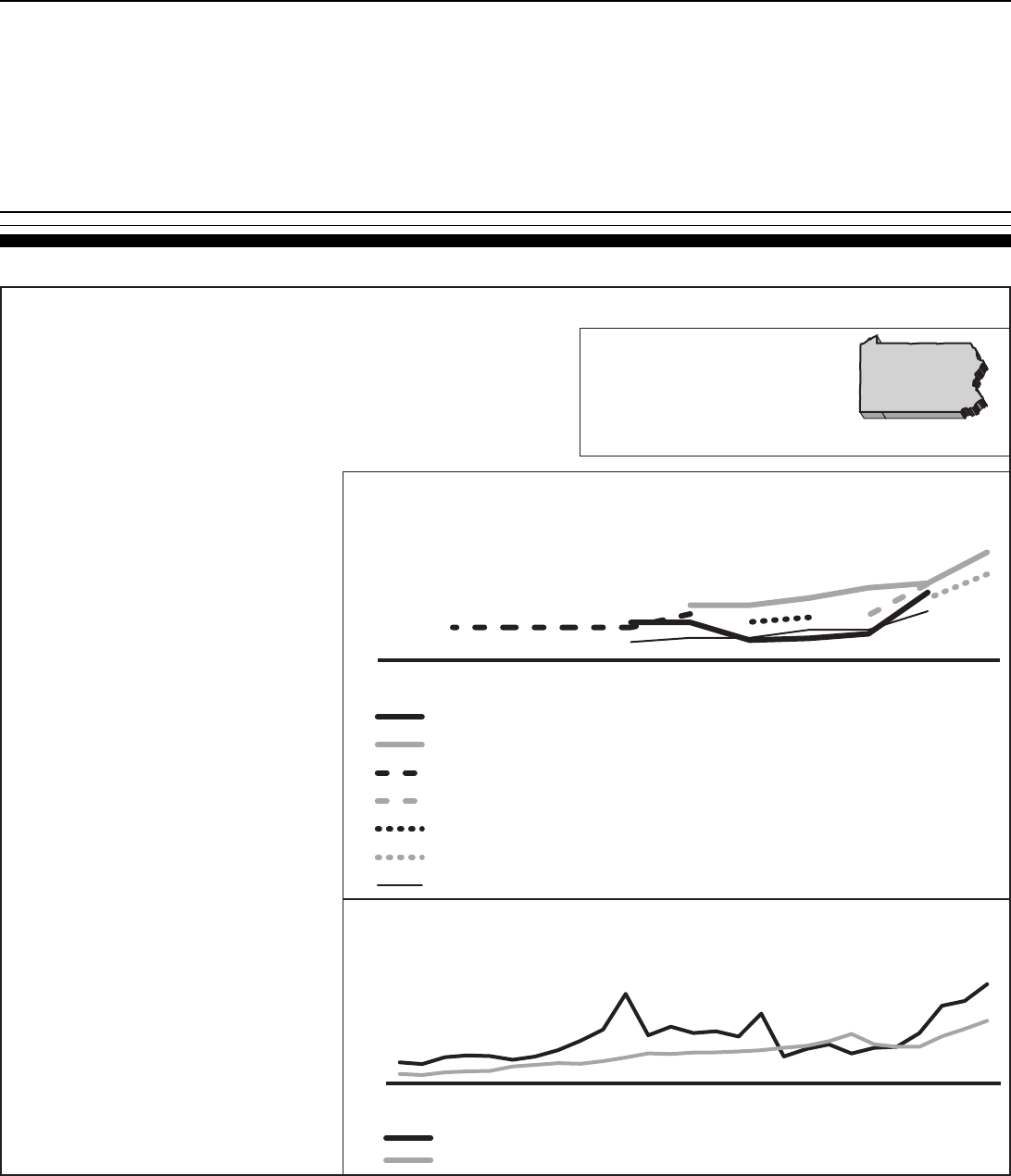

As figure 1 shows, premium base rates varied across our seven sample

states from 1992 to 1998 but for most insurers remained relatively flat.

Beginning in 1999 and 2000, however, most of these insurers began

increasing their rates in larger increments. Many of the increases were

dramatic, ranging as high as 165 percent, although some rates remained

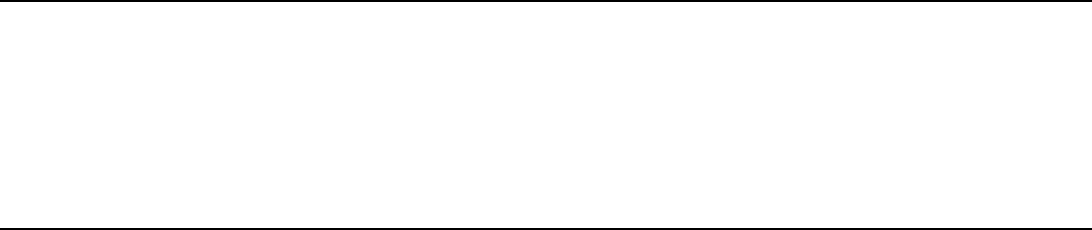

flat. Figure 2 shows the percentage increase in premium rates for the

largest insurers in our seven sample states from 1999 through 2002.

21

In the

Harrisburg area of Pennsylvania, for example, the largest insurer increased

premium base rates dramatically for three specialties: obstetrics/

gynecology (165 percent), general surgery (130 percent), and internal

medicine (130 percent). At the same time, the consumer price index (CPI)

increased by 10 percent. However, in California and Minnesota, premium

base rates for the same specialties rose between 5 and 21 percent and in

some cases fell slightly. The variations in the changes in premium base

rates among our sample states appears to be consistent with the changes in

states outside our sample, with insurers in some states raising premium

rates rapidly after 1999 and insurers in other states raising them very little.

20

In this report, premium rates shown for Pennsylvania include a surcharge for a mandatory

professional liability catastrophe loss fund. Policies purchased from an insurer provide

coverage up to a specific amount, and the loss fund then provides additional coverage. The

amount required to be covered by insurers has been increasing and the amount covered by

the loss fund has been decreasing. In 2002, insurers covered the first $500,000 of any claim,

up to an annual limit of $1.5 million, while the loss fund covered an additional $400,000 per

claim, up to an annual limit of $1.2 million.

21

We determined the largest insurers in each of our seven sample states based on premiums

written in 2001.

Page 11 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

Figure 1: Premium Base Rates of the Largest Insurers in Seven Selected States for

Three Medical Specialties, 1992–2002

Note: Premium rates shown are annual premium rates for a claims-made policy with a cap of $1 million

per incident and $3 million per year.

Source: GAO analysis of annual surveys by the Medical Liability Monitor.

Pennsylvania Medical Society Liability Insurance

Company in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (1997-2002)

Texas Medical Liability Trust in El Paso, Texas (1996-2002)

Medical Insurance Exchange of California in Clark County Nevada (1993-2002)

Doctors Company in northern California

First Professionals Insurance Company in Palm Beach County, Florida

Medical Assurance of Mississippi in Mississippi

Midwest Medical Insurance Company in Minnesota

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

20022001200019991998199719961995199419931992

General surgery

Dollars in thousands

0

10

20

30

40

20022001200019991998199719961995199419931992

Internal medicine

Dollars in thousands

0

30

60

90

120

150

20022001200019991998199719961995199419931992

Dollars in thousands

Obstetrics/gynecology

Page 12 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

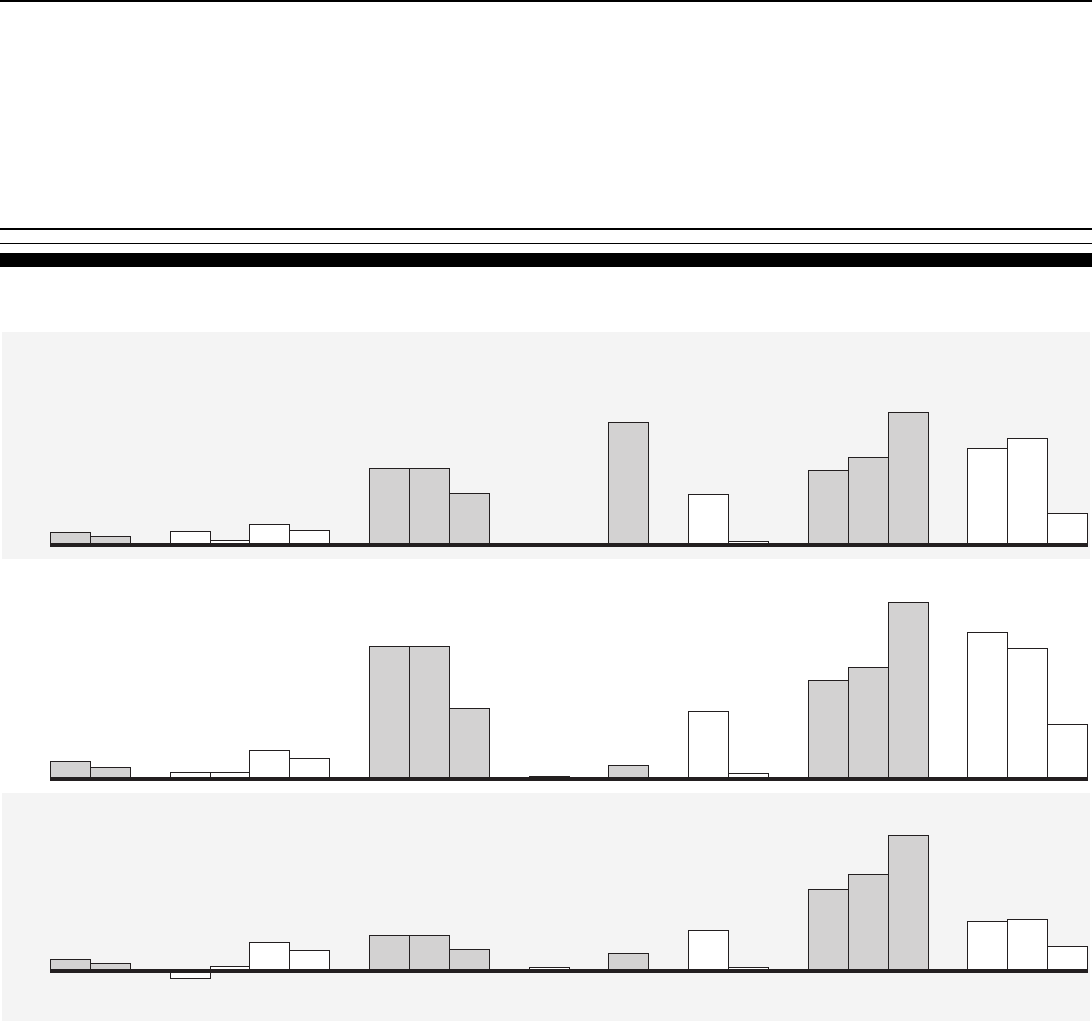

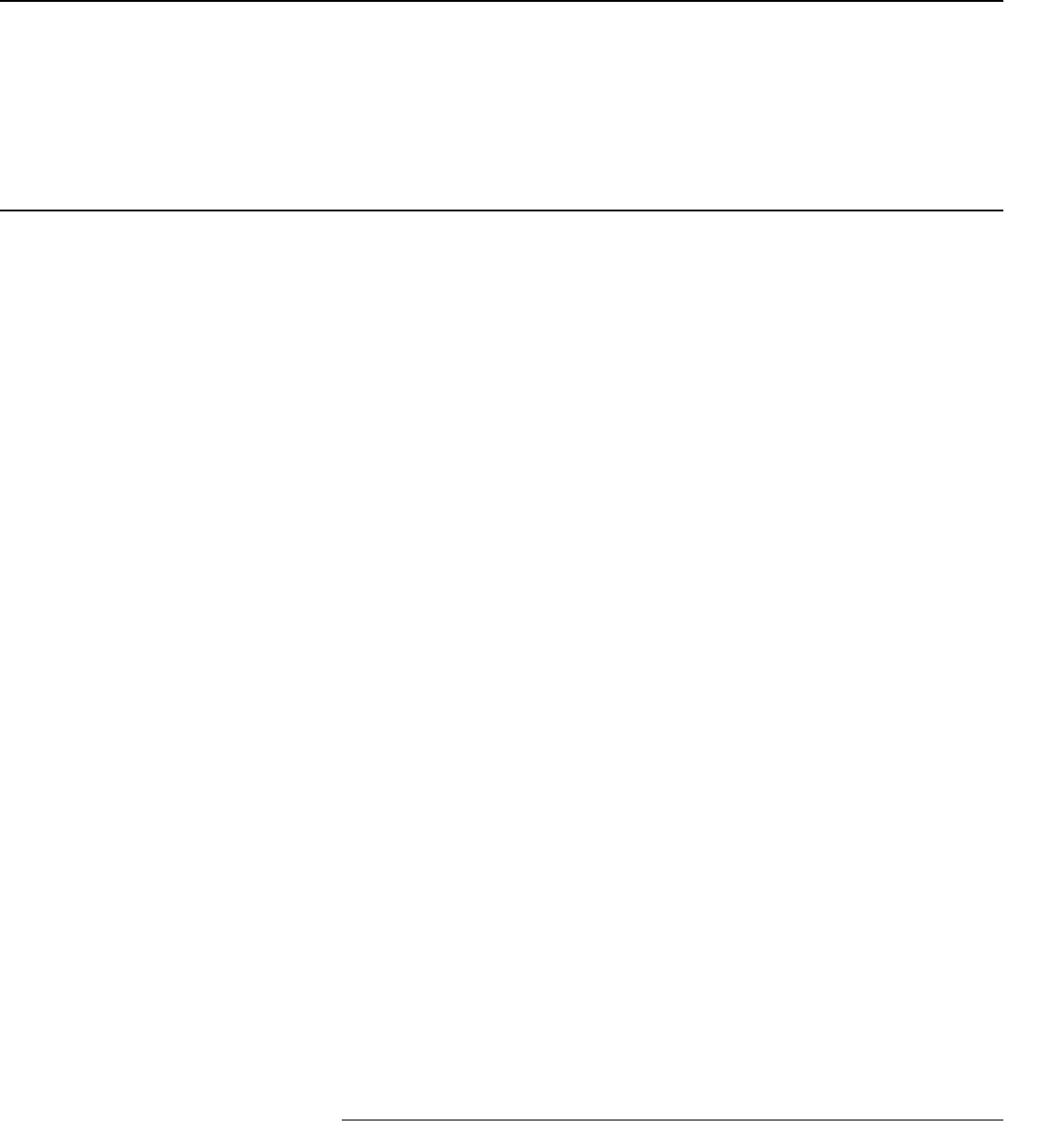

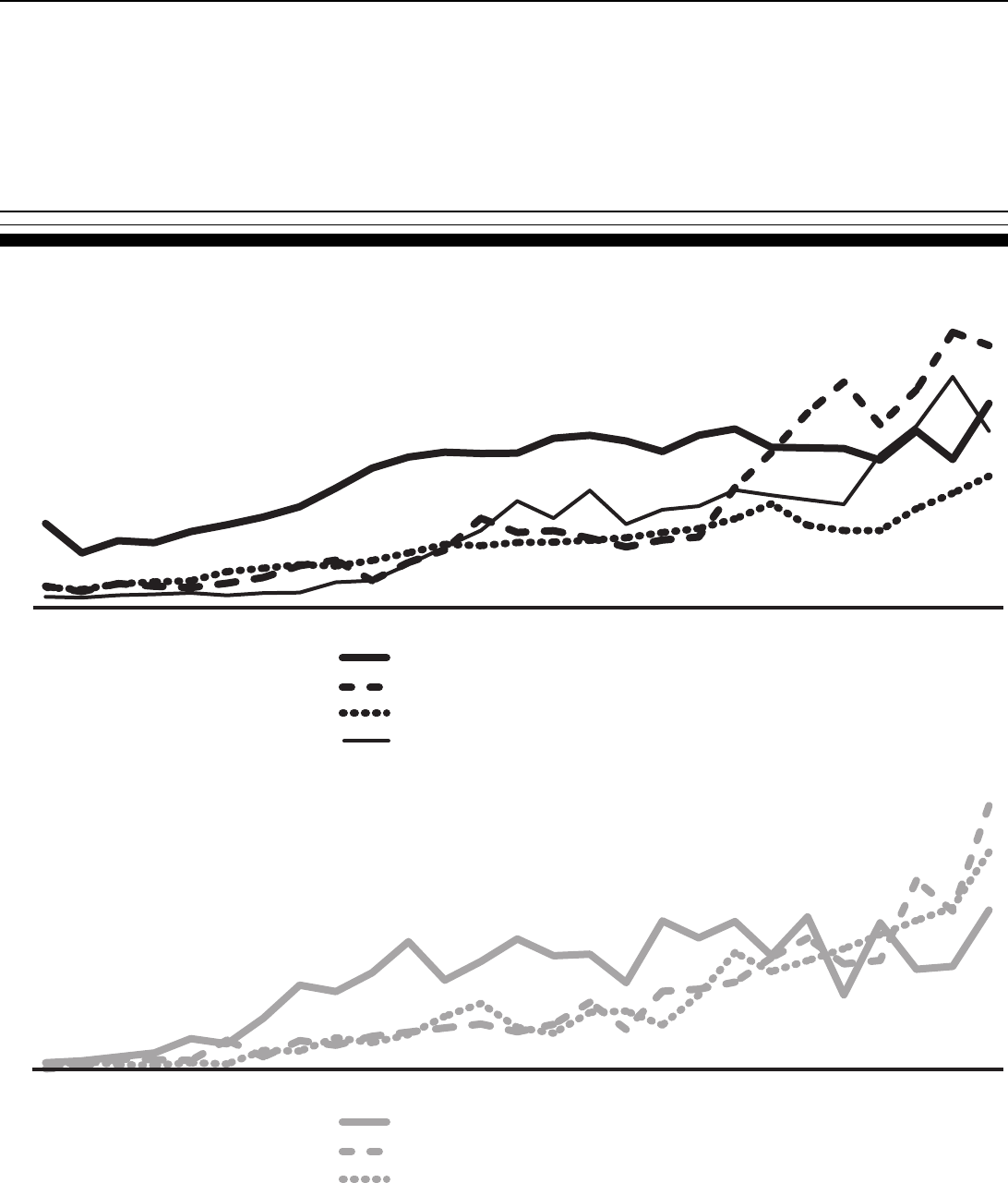

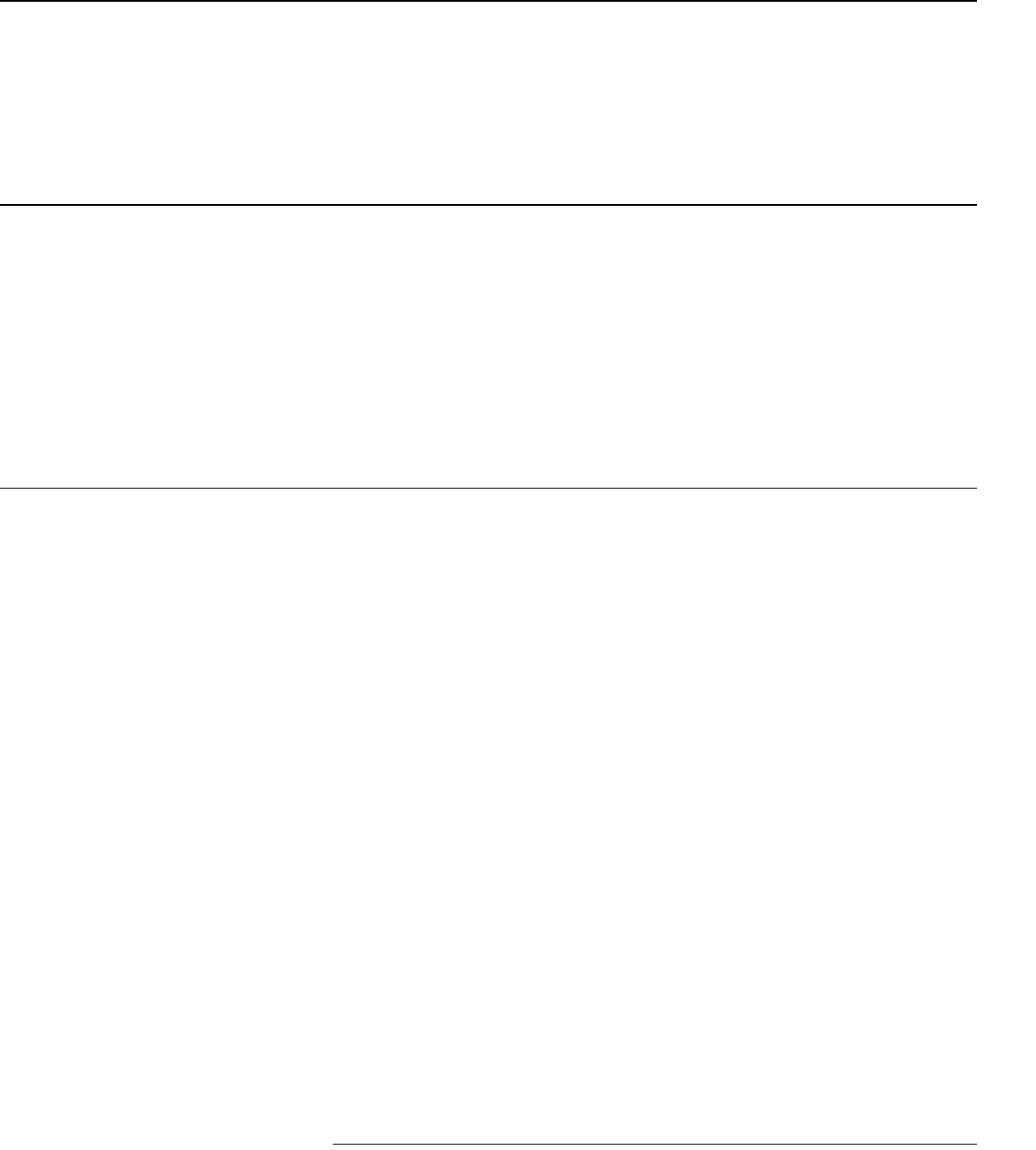

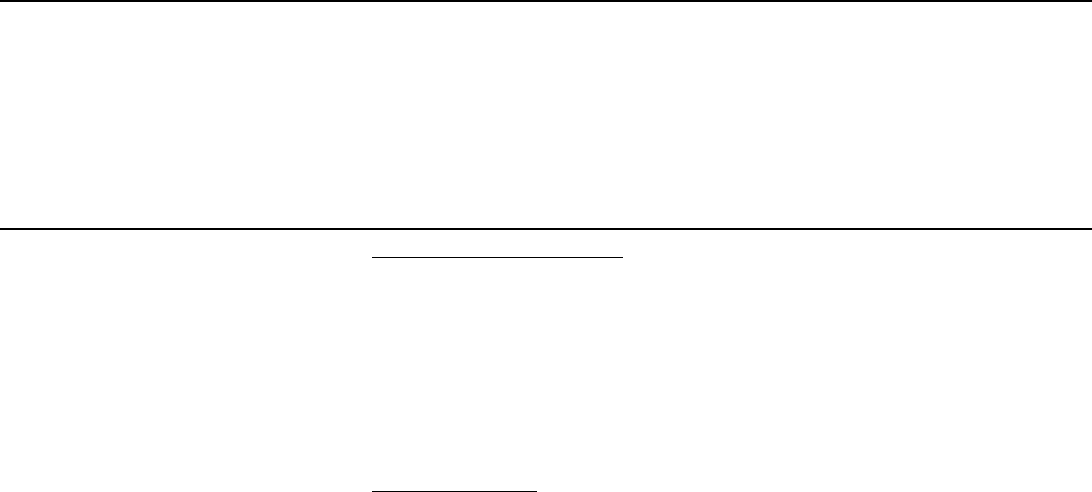

Figure 2: Percentage Changes in Premium Base Rates of the Largest Medical Malpractice Insurers in Seven Selected States for

Three Medical Specialties, 1999–2002

Source: GAO analysis of annual surveys by the Medical Liability Monitor.

Medical Assurance

(Dallas, Texas, area)

Texas Medical Liability

Trust (Amarillo, Texas, area)

Texas Medical Liability

Trust (El Paso, Texas, area)

Pennsylvania Medical Society Liability

Insurance Company (Harrisb

urg area)

Pennsylvania Medical Society Liability

Insurance Company (Pittsburgh area)

Pennsylvania Medical Society Liability

Insurance Company (Philadelphia area)

Medical Insurance Exchange of California

(Nevada, outside of Clark County)

Medical Insurance Exchange

of California

(Clark County, Nevada)

Medical Assurance of

Mississippi (Mississipp

i)

Midwest Medical Insurance

Company (Minnesota)

Medical Assurance (Palm Beach, Florida)

First Professionals Insurance

Company (rest of Florida)

First Professionals Insurance

Company (Dade County, Florida)

Southern California Physician's

Insurance Exchange (Los Angeles Cou

nty)

Southern California Physician's

Insurance Exchange (Sa

n Diego, California)

Medical Insurance Exchange

of California (northern California)

Doctor's Company (northern California)

Cumulative General CPI

Cumulative

Medical Care CPI

General surgery

Internal medicine

Obstetrics/gynecology

-50

0

50

100

150

200

Percentage increase

0

30

60

90

120

150

Percentage increase

0

50

100

150

200

Percentage increase

18

10

14

5

21

15

75 75

51

2

120

50

4

73

82

130

95

104

31

18

10

5

5

21

21

15

15

98 98

52

2

2

10

50

4

73

82

130

108

96

40

18

10

-9

5

43 43

26

21

50

4

99

110

165

60

62

30

Fla. Nev. Tex.Cal. Miss.Minn. Pa.

Fla. Nev. Tex.Cal. Miss.Minn. Pa.

Fla. Nev. Tex.Cal. Miss.Minn. Pa.

Page 13 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

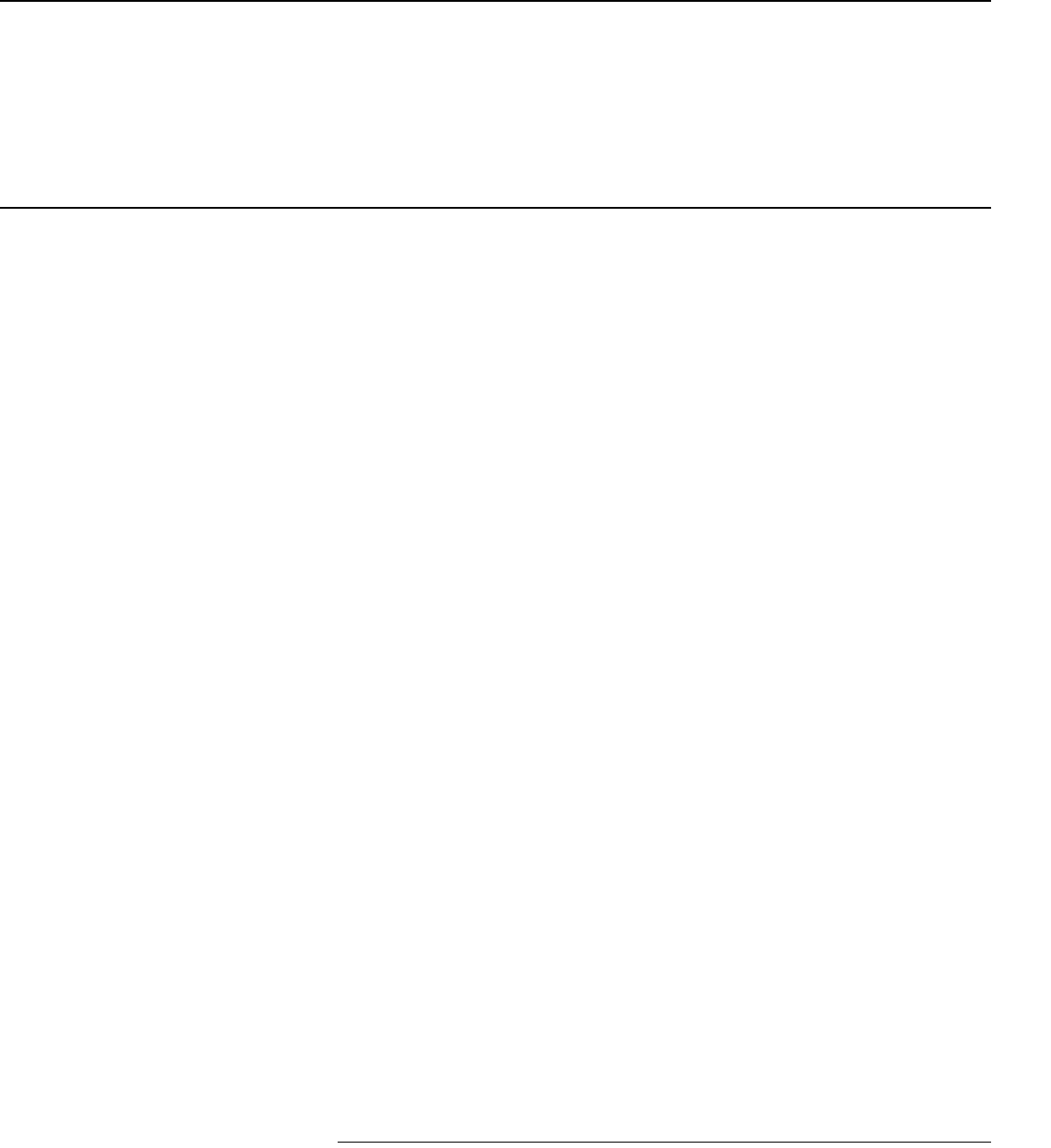

The Level of Premium Rates

Also Varied across

Specialties and States

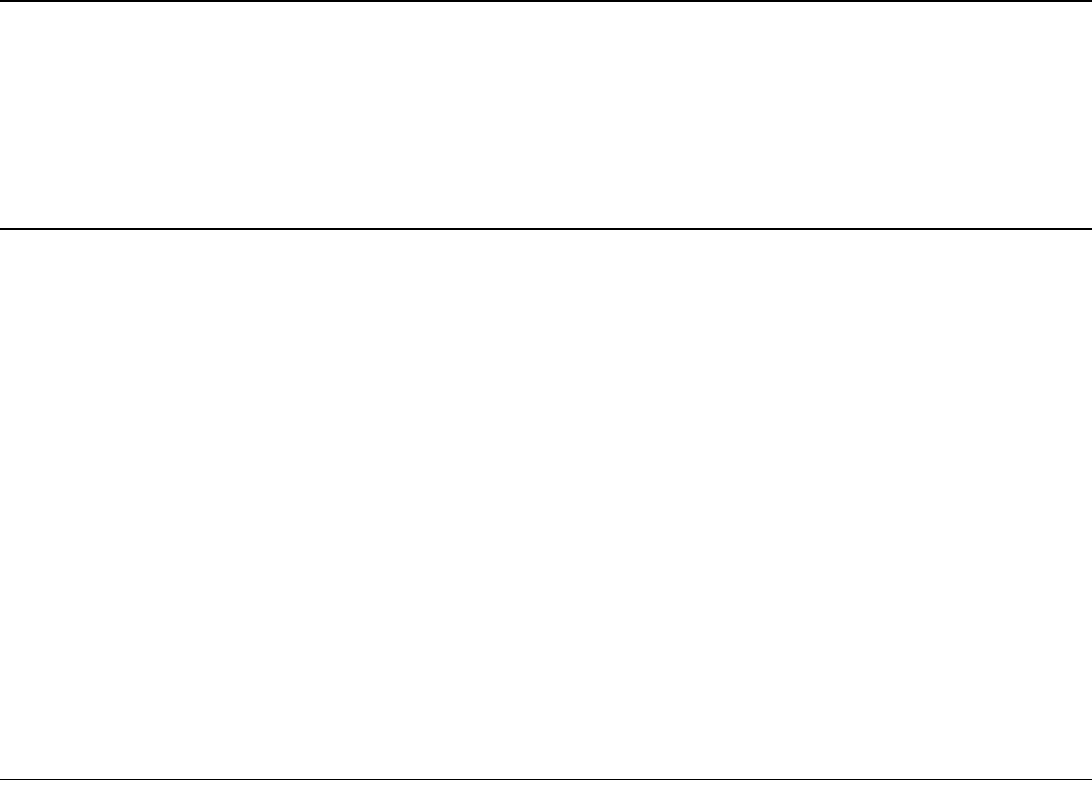

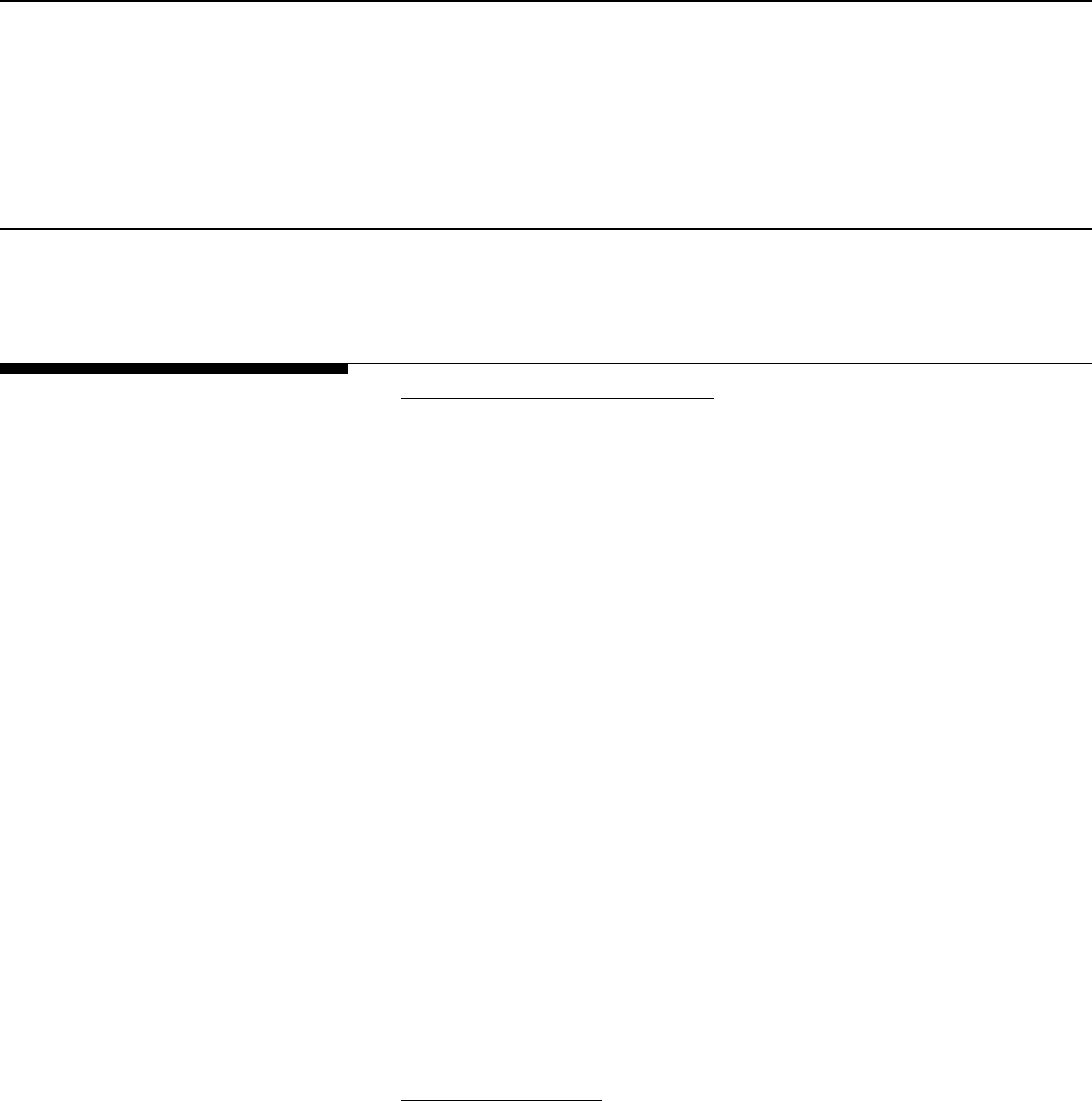

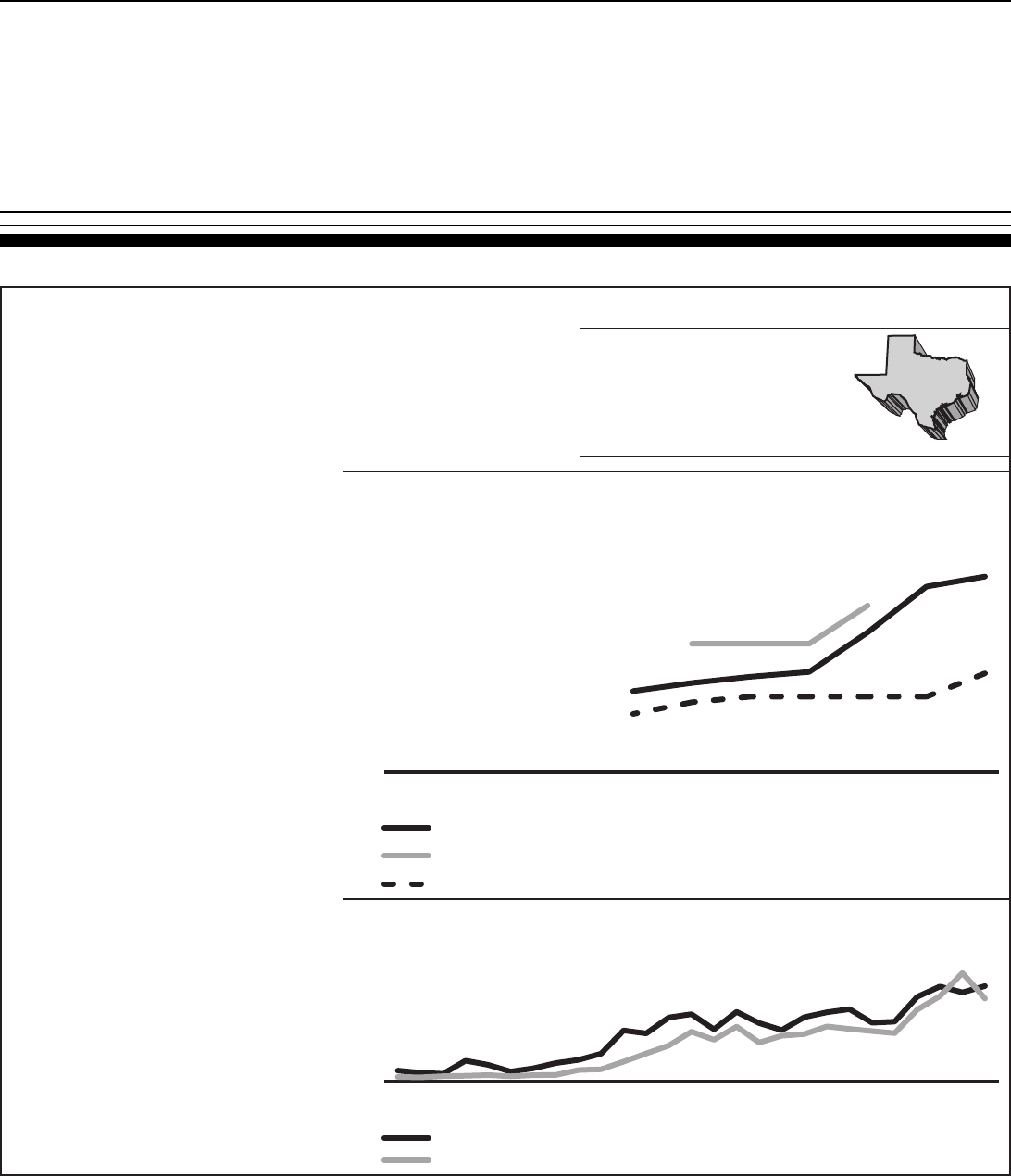

We found that premium rates quoted by insurers in our seven sample states

varied across medical specialties and states. According to some of the

insurers and actuaries we spoke with, the differences in rates reflect the

costs associated with medical malpractice claims against physicians in

particular specialties. Specialties with a high risk of large or frequent losses

on medical malpractice claims will have higher premium rates. For

example, in 2002 the largest medical malpractice insurer in Texas quoted a

base rate for the same level of coverage of $92,000 to obstetricians and

gynecologists, $71,000 to general surgeons, and $26,000 to internists. Figure

3 shows the premium rates quoted by the largest medical malpractice

insurers in our sample states for these three specialties.

22

Premium rates quoted by insurers in our seven sample states for the same

medical specialty also varied across states and geographic areas within

states (see fig. 3). Some of the insurers and actuaries we spoke with told us

that these variations also reflect differences in insurers’ loss experiences in

those venues. As figure 3 shows, the largest insurer in Florida quoted a

premium base rate of $201,000 for obstetricians and gynecologists in Dade

County, while the largest insurer in California quoted a premium based rate

of $36,000 for similar physicians in northern California. Within Florida, the

same large insurer quoted a premium base rate of $103,000 for

obstetricians and gynecologists outside of Dade County—approximately 51

percent of the Dade County rate. Within Pennsylvania, the largest insurer

quoted a premium base rate of $64,000 for doctors in Philadelphia—

approximately 83 percent more than the rate it quoted outside the city.

22

Not all of the insurers included in figs. 3 and 4 are the same, as data that would have

allowed us to complete the same analyses for all of the insurers was not available.

Page 14 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

Figure 3: 2002 Medical Malpractice Insurance Premium Base Rates of the Largest Insurers in Seven Selected States for Three

Medical Specialties

Note: Premium rates shown are annual premium base rates for coverage under a claims-made policy

with a cap of $1 million per incident and $3 million per year.

Source: GAO analysis of annual surveys by the Medical Liability Monitor.

Texas Medical LiabilityTrust

(Texas's lowest rated territory)

Texas Medical Liability Trust

(Texas's highest rated territory)

First Professionals Insurance

Company (Dade County, Florida)

Southern California Physician's

Insurance Exchange

(southern California)

Norcal

(central California)

Doctor's Company

(northern California)

Pennsylvania Medical Society Liability

Insurance Company (Pittsburgh area)

Pennsylvania Medical Society Liability

Insurance Company (Philadelphia area)

Medical Insurance Exchange of California

(Nevada, outside of Clark County)

Medical Insurance Exchange

of California

(Clark County, Nevada)

Medical Assuran

ce of

Mississippi (Mississippi)

Midwest Medical Insurance

Company (Minnesota)

First Professionals Insurance

Company (rest of Florida)

General surgery

Internal medicine

Obstetrics/gynecology

0

50

100

150

200

250

Dollars in thousands

Dollars in thousands

Dollars in thousands

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

0

50

100

150

200

22

27

34

174

89

10

33

50

28

71

34

85

51

6

12 12

56

29

4

5

11

6

26

13

24

14

31

36

55

201

103

17

45

64

35

92

43

142

85

Fla.

Nev.Tex.Cal. Miss.Minn. Pa.

Nev.Tex.Cal. Miss.Minn. Pa.

Nev.Tex.Cal. Miss.Minn. Pa.

Fla.

Fla.

Page 15 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

Multiple Factors Have

Contributed to the

Increases in Medical

Malpractice Premium

Rates

Insurers’ losses, declines in investment income, a less competitive climate,

and climbing reinsurance rates have all contributed to rising premium

rates. First, among our seven sample states, insurers’ losses have increased

rapidly in some states, increasing the amount that insurers expect to pay

out on future claims. Second, on the national level insurers’ investment

income has decreased, so that insurance companies must increasingly rely

on premiums to cover costs. Third, some large medical malpractice

insurers have left the market in some states because selling policies was no

longer profitable, reducing the downward competitive pressure on

premium rates that existed through most of the 1990s. Last, reinsurance

rates for some medical malpractice insurers in our seven sample states

have increased substantially, increasing insurers’ overall costs. In

combination, all the factors affecting premium rates and the availability of

medical malpractice insurance contribute to the medical malpractice

insurance cycle of hard and soft markets. While predicting the length, size

and turning points of a cycle may be impossible, it is clear that the

relatively long period of time required to resolve medical malpractice

claims makes the cycles more extreme in this market than in other

insurance markets.

Increased Losses on Claims

Are the Primary Contributor

to Higher Medical

Malpractice Premium Rates

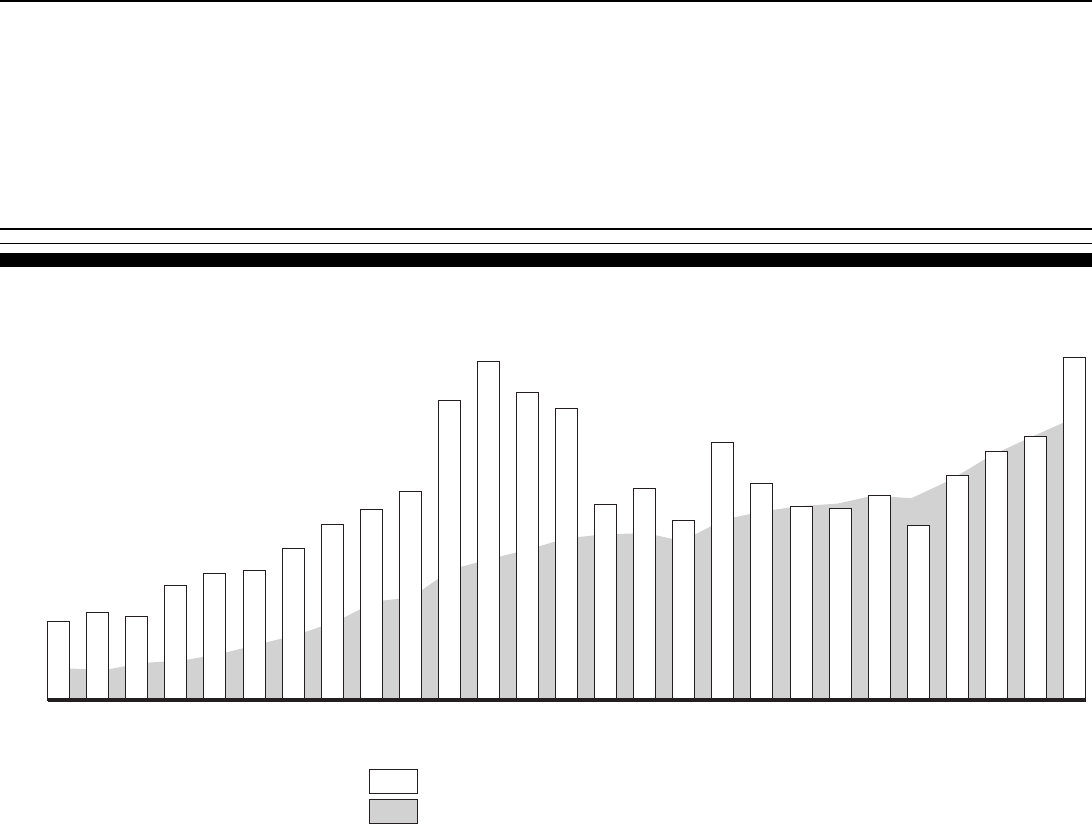

Like premium increases, annual paid losses and incurred losses for the

national medical malpractice insurance market began to rise more rapidly

beginning in 1998.

23

After adjusting for inflation, we found that the average

annual increase in paid losses from 1988 to 1997 was approximately 3.0

percent but that this rate rose to 8.2 percent from 1998 through 2001.

Inflation-adjusted incurred losses decreased by an average annual rate of

3.7 percent from 1988 to 1997 but increased by 18.7 percent from 1998 to

2001. Figure 4 shows paid and incurred losses for the national medical

malpractice market from 1975 to 2001, adjusted for inflation.

23

Over the past several years, some large medical malpractice insurers in some states have

become insolvent. Such insolvencies may have caused aggregate paid losses in those states

to be understated to an unknown extent, because while the insurer may still be paying

medical malpractice claims, they may no longer be reporting those payments to NAIC or

state regulators.

Page 16 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

Paid and incurred losses give different pictures of an insurer’s loss

experience, and examining both can help provide a better understanding of

an insurer’s losses.

24

Paid losses are the cash payments an insurer makes in

a given year, irrespective of the year in which the claim giving rise to the

payment occurred or was reported. Most payments made in any given year

are for claims that were reported in previous years. In contrast, incurred

losses in any single year reflect an insurer’s expectations of the amounts

that will be paid on claims reported in that year. Incurred losses for a given

year will also reflect any adjustments an insurer makes to the expected

amounts that must be paid out on claims reported during previous years.

That is, as more information becomes available on a particular claim, the

insurer may find that the original estimate was too high or too low and

must make an adjustment. If the original estimate was too high, the

adjustment will decrease incurred losses, but if the original estimate was

too low, the adjustment will increase them.

Incurred losses are the largest component of medical malpractice insurers’

costs. For the 15 largest medical malpractice insurers in 2001—whose

combined market share nationally was approximately 64.3 percent—

incurred losses (including both payments to plaintiffs to resolve claims and

the costs associated with defending claims) comprised, on average, around

78 percent of the insurers’ total expenses. Because insurers base their

premium rates on their expected costs, their anticipated losses will

therefore be the primary determinant of premium rates.

24

According to at least one insurer, the best measure of the results from policies may be the

ultimate paid losses on the claims reported that year, which insurers could compare to the

premiums charged for the policies in question. However, as paid losses are not entirely

known for at least 3 to 5 years after they claims are reported, such information is not

completely available for the years 1998 through 2002.

Page 17 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

Figure 4: Inflation-Adjusted Paid and Incurred Losses for the National Medical Malpractice Insurance Market, 1975–2001 (Using

the CPI, in 2001 Dollars)

Source: GAO analysis of A.M. Best data.

Dollars in millions

0

1,000

2,000

3,000

4,000

5,000

6,000

7,000

2001

2000

1999

1998

1997

1996

1995

1994

1993

1992

1991

1990

1989

1988

1987

1986

1985

1984

1983

1982

1981

1980

1979

1978

1977

1976

1975

Direct losses incurred in 2001 dollars

Direct losses paid in 2001 dollars

Page 18 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

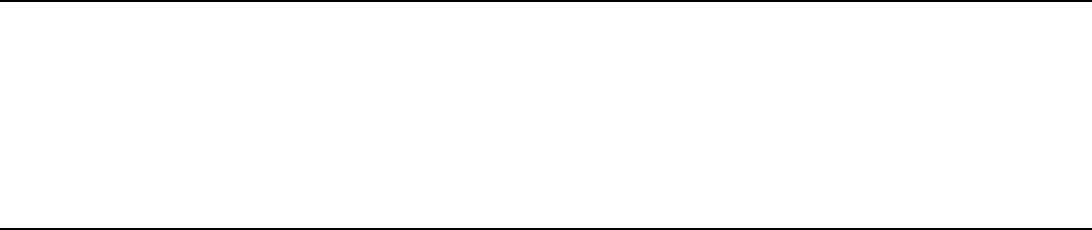

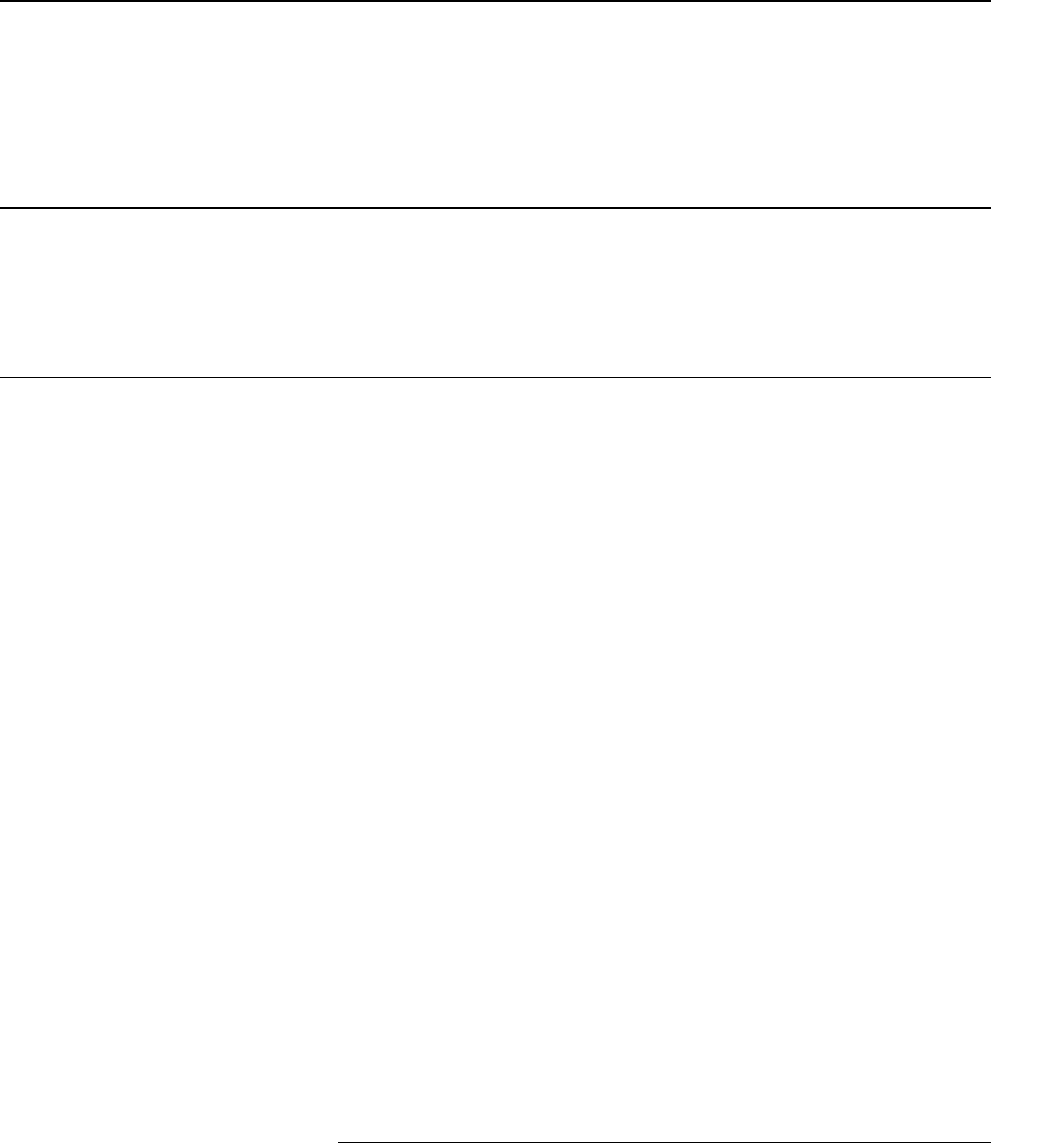

The recent increases in both paid and incurred losses among our seven

sample states varied considerably, with some states experiencing

significantly higher increases than others. From 1998 to 2001, for example,

paid losses in Pennsylvania and Mississippi increased by approximately

70.9 and 142.1 percent, respectively, while paid losses in California and

Minnesota increased by approximately 38.7 and 8.7 percent, respectively

(see fig. 5).

25

Because paid losses in any single year reflect primarily claims

reported during previous years, these losses may not be representative of

claims that were reported during the year the losses were paid.

25

To better show annual changes in the states with smaller total losses, in both figs. 5 and 6

we have separated our seven sample states into two groups, those with smaller total losses

and those with greater total losses.

Page 19 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

Figure 5: Inflation-Adjusted Aggregate Paid Losses for Medical Malpractice Insurers in Seven Selected States, 1975-2001 (Using

the CPI, in 2001 Dollars)

Source: GAO analysis of A.M. Best data.

Texas

Pennsylvania

Florida

California

Nevada

Mississippi

Minnesota

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

200120001999199819971996199519941993199219911990198919881987198619851984198319821981198019791978197719761975

Dollars in millions

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

200120001999199819971996199519941993199219911990198919881987198619851984198319821981198019791978197719761975

Dollars in millions

Page 20 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

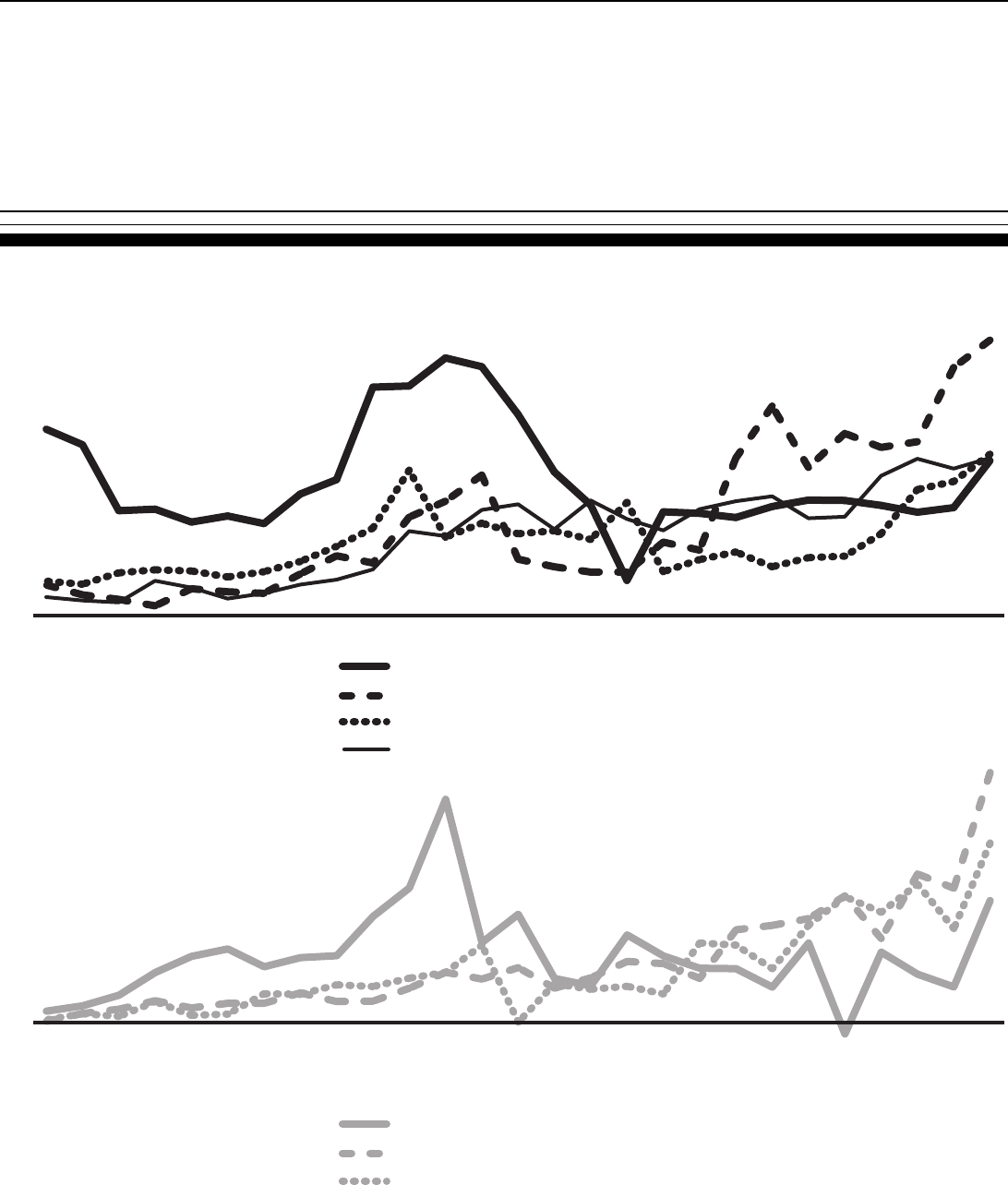

From 1998 to 2001, aggregate incurred losses increased by large amounts in

almost all of our seven sample states. As shown in figure 6, the highest

rates of increase in incurred losses over that period were experienced by

insurers in Mississippi (197.5 percent) and Pennsylvania (97.2 percent).

Even in California and Minnesota, states with lower paid losses from 1998

through 2001, insurers experienced increases in incurred losses of

approximately 40.5 and 73.2 percent, respectively, over the same period. As

noted above, incurred losses in any single year reflect insurers’

expectations of future paid losses associated with claims reported in the

current year—that is, claims that will be paid, on average, over the next 3

and one-half years (according to one industry association). And because

insurers’ incurred losses have increased recently, insurers are expecting

their paid losses to increase over the next several years.

Page 21 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

Figure 6: Inflation-Adjusted Aggregate Incurred Losses for Medical Malpractice Insurers in Seven Selected States, 1975-2001

(Using the CPI, in 2001 Dollars)

Source: GAO analysis of A.M. Best data.

Texas

Pennsylvania

Florida

California

Nevada

Mississippi

Minnesota

Dollars in millions

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

200120001999199819971996199519941993199219911990198919881987198619851984198319821981198019791978197719761975

Dollars in millions

-20

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

200120001999199819971996199519941993199219911990198919881987198619851984198319821981198019791978197719761975

Page 22 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

Increased Losses Lead to Higher

Premium Rates

According to actuaries and insurers we spoke with, increased paid losses

raise premium rates in several ways. First, higher paid losses on claims

reported in current or previous years can increase insurers’ estimates of

what they expect to pay out on future claims. Insurers then raise premium

rates to match their expectations. In addition, large losses (particularly

paid losses) on even one or a few individual claims can make it harder for

insurers to predict the amount they might have to pay on future claims.

Some insurers and actuaries we spoke with told us that when losses on

claims are hard to predict, insurers will generally adopt more conservative

expectations regarding losses—that is, they will assume losses will be

toward the higher end of a predicted range of losses. Further, large losses

on individual claims can raise plaintiffs’ expectations for damages on

similar claims, ultimately resulting in higher losses across both claims that

are settled and those that go to trial. As described above, this tendency in

turn can lead to higher expectations of future losses and thus to higher

premium rates. Finally, an increase in the percentage of claims on which

insurers must make payments can increase the amount that insurers expect

to pay on each policy, resulting in higher premium rates. That is, insurers

expecting to pay out money on a high percentage of claims may charge

more for all policies in order to cover the expected increases.

Comprehensive Data on the

Composition and Causes of

Increased Losses Were Lacking

A lack of comprehensive data at the national and state levels on insurers’

medical malpractice claims and the associated losses prevented us from

fully analyzing both the composition and causes of those losses at the

insurer level.

26

For example, comprehensive data that would have allowed

us to fully analyze the severity of medical malpractice claims at the insurer

level on a state-by-state basis did not exist. To begin with, data submitted

by insurers to NAIC on the number of claims reported to insurers are not

broken out by state. Rather, insurers that operate in a number of states

report the number of claims for all their medical malpractice insurance

policies nationwide. Also, while NAIC does collect data that can be used to

measure the severity of claims paid in a single year (number of claims per

state), NAIC began this effort only in 2000. As a result, we could not gather

enough data to examine trends in the severity of paid claims from 1998 to

2002 at the insurer level. Similarly, comprehensive data did not exist that

would have allowed us to analyze claim frequency on a state-by-state basis.

As noted above, data that insurers submit to NAIC on the number of claims

reported were not broken out by state prior to 2000. In addition, insurers do

26

Some additional data on medical malpractice claims, not connected to individual insurers,

were available and were analyzed in a separate report. See GAO-03-836.

Page 23 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

not submit information on the number of policies in effect or the number of

health care providers insured. Finally, medical associations we spoke with

in our sample states had not compiled accurate data on the number of

physicians practicing within those states. As a result, we could not analyze

changes in the frequency of medical malpractice claims in our sample

states at the insurer level.

Data that would have allowed us to analyze how losses were divided

between settlements and trial verdicts or between economic and

noneconomic damages were also not available. First, insurers do not

submit information to NAIC on the portion of losses paid as part of

settlements and the portion paid as the result of a trial verdict, and no other

comprehensive source of such information exists. However, all eight

insurers and one of the trial lawyers’ associations we spoke with provided

certain estimates about claims. The estimates of three insurers on the

percentage of claims resulting in trial verdicts ranged from 5 to 7 percent.

The estimates of four insurers and 1 state trial lawyers’ association of the

percentage of trial verdicts being decided in favor of the insured defendant

ranged from 70 to 86 percent. The estimates of four insurers and one state

trial lawyers’ association of the portion of claims resulting in payment to

the plaintiff ranged from 14 to 50 percent. Second, no comprehensive

source of information exists on the breakdown of losses between

economic damages, such as medical costs and lost wages, and

noneconomic damages, such as compensation for pain and suffering.

Several of the insurers and trial lawyers’ associations we spoke with noted

that settlement amounts are not formally divided between these two types

of damages and that consistent, comprehensive information on trial

judgments is not collected. Furthermore, while judgment amounts obtained

at trial may be large, several of the insurers we spoke with said that they

most often do not pay amounts beyond a policyholder’s policy limits.

27

Data on the final amounts insurers pay out on individual judgments are not

collected, although they are reported in the aggregate as part of paid losses

in insurers’ financial statements.

27

Some insurers we spoke with told us that they can be liable for amounts beyond a policy’s

limits if the policyholder requests that the insurer settle with the plaintiff for an amount

equal to or less than the policy limit, but the insurer takes the case to trial, loses, and a

judgment is entered in an amount greater than the policy limits. Insurers in California,

Florida, and Texas told us that payments beyond policy limits posed significant issues in

their states.

Page 24 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

While losses on medical malpractice claims increase as the cost of medical

care and the value of lost wages rise, losses in some states have far

outpaced such inflation. Insurance, legal, and medical industry officials we

spoke with suggested a number of potential causes for such increases.

These potential causes included a greater societal propensity to sue; a

“lottery mentality,” where a lawsuit is seen as an easy way to get a large

sum of money; a sicker, older population; greater expectations for medical

care because of improved technology; and a reduced quality of care and the

breakdown of the doctor-patient relationship owing, for example, to factors

such as the increasing prevalence of managed care organizations. While we

could not analyze such potential causes for increased losses,

understanding them would be useful in developing strategies to address

increasing medical malpractice premium rates. That is, because losses on

claims have such a profound effect on premium rates, understanding the

reasons those losses have increased could make it easier to devise actions

to control the rise in premium rates.

28

Medical Malpractice

Insurers’ Investment

Income Has Decreased

State laws restrict medical malpractice insurers to conservative

investments, primarily bonds. In 2001, the 15 largest writers of medical

malpractice insurance in the United States

29

invested, on average, around

79 percent of their investment assets in bonds, usually some combination

of U.S. Treasury, municipal, and corporate bonds. While the performance of

some bonds has surpassed that of the stock market as a whole since 2000,

annual yields on selected bonds since 2000 have decreased steadily since

then (table 1).

28

State laws for resolving medical malpractice claims may also affect the extent to which

losses increase in a particular state. The effect of state laws on losses and premium rates is

discussed in greater detail in GAO-03-836.

29

As reported by A.M. Best. These insurers included a combination of commercial

companies and physician-owned nonprofit insurers. Some of these insurers sold more than

one line of insurance, and changes in returns on investments might not be reflected equally

in the premium rates in each of those lines.

Page 25 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

Table 1: Annual Yields for Selected Bonds, 1995–2002, and Average Return on Investment Assets, 1997–2002, for the 15 Largest

Writers of Medical Malpractice Insurance in 2001

Source: GAO analysis of data from A.M. Best, the Federal Reserve, and the Bond Market Association.

a

Data for 1995 and 1996 were not readily available.

b

Complete information was not available for the same companies in 2002. The 2002 average return on

investment was estimated based on the average bond yield and the average ratio of the bond yield to

the insurer’s return on investment.

We analyzed the average investment returns of the 15 largest medical

malpractice insurers of 2001 and found that the average return fell from

about 5.6 percent in 2000 to an estimated 4.0 percent in 2002. However,

none of the companies experienced a net loss on investments at least

through 2001, the most recent year for which such data were available.

Additionally, almost no medical malpractice insurers overall experienced

net investment losses from 1997 to 2001.

Medical malpractice insurers are required by state insurance regulations to

reflect expected investment income in their premium rates. That is,

insurers are required to reduce their premium rates to consider the income

they expect to earn on their investments. As a result, when insurers expect

their returns on investments will be high, as returns were during most of

the 1990s, premium rates can remain relatively low because investment

income covers a larger share of losses on claims. Conversely, when

insurers expect their returns on investments will be lower—as returns have

been since around 2000—premium rates rise in order to cover a larger

share of losses. During periods of relatively high investment income,

insurers can lose money on the underwriting portion of their business yet

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002

5-Year U.S. Treasury

securities 6.38 6.18 6.22 5.15 5.55 6.16 4.56 3.82

10-Year U.S. Treasury

securities 6.57 6.44 6.35 5.26 5.65 6.03 5.02 4.61

5-Year AAA-rated municipal

bonds 4.57 4.41 4.34 3.97 4.18 4.72 3.63 3.16

10-Year AAA-rated municipal

bonds 5.04 4.91 4.75 4.31 4.62 4.97 4.28 4.05

5-Year AAA-rated corporate

bonds 6.71 6.49 6.52 5.61 6.17 6.96 5.24 4.45

10-Year AAA-rated corporate

bonds 6.93 6.77 6.66 5.74 6.38 7.09 5.92 5.42

Average return on investment

assets for 15 largest insurers

aa

5.6 5.5 5.2 5.6 5.0 4.0

b

Page 26 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

still make a profit. That is, losses from medical malpractice claims and the

associated expenses may exceed premium income, but income from

investments can still allow the insurer to operate profitably. Insurers are

not allowed to increase premium rates to compensate for lower-than-

expected returns on past investments but must consider only prospective

income from investments.

None of the insurers that we consulted regarding this issue told us

definitively how much the decreases in investment income had increased

premium rates. But we can make a rough estimate of the relationship

between return on investment and premium rates. When investment

income decreases, holding all else constant, income from premium rates

must increase by an equal amount in order for the insurer to maintain the

same overall level of income. Thus the total amount of investment assets

relative to premium income determines how much rates need to rise to

compensate for lost investment income. Table 2 presents a hypothetical

example. An insurer has $100,000 in investment assets and in the previous

year received $25,000 in premium income, for a ratio of investment assets

to premium income of 4 to 1. If the return on investments drops 1

percentage point and all else remains constant, the insurer must raise

premium rates by 4 percent in order to compensate for the reduced

investment income. If the return on investments drops by 2 percentage

points, premium rates must rise by 8 percent to compensate.

Page 27 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

Table 2: Hypothetical Example of How Premium Rates Change When the Return on

Investments Falls

Source: GAO analysis.

Note: The examples given assume that all else holds constant and that the insurer must obtain the full

amount of additional funds required in the following year, even though the insurer would earn interest

on those funds and thus would not need to increase premium rates by the full amount. Such an

assumption may overstate the extent to which premium rates must be increased. The examples also

do not take into account the fact that insurers look prospectively at trends in interest rates when

estimating their anticipated investment income. By not taking into account a downward trend in interest

rates, such as the one that has existed since 2000, our examples may understate the needed increase.

This relationship can be applied to the 15 largest medical malpractice

insurers—countrywide—from 2001. Data show that in 2001 the insurers’

total investment assets were, on average, around 4.5 times as large as the

amount of premium income they earned for that year. Applying the

relationship established above and holding other factors constant, a drop

of 1 percentage point in return on investments would translate into roughly

a 4.5 percent increase in premium rates.

30

As a result, if nothing else

changed, the approximately 1.6 percentage point drop in the return on

investments these insurers experienced from 2000 through 2002 would

have resulted in an increase in premium rates of around 7.2 percent over

the same 2-year period.

Example 1 Example 2 Example 3

(a) Total investment assets $100,000 $100,000 $100,000

(b) Original total premium

income $25,000 $25,000 $25,000

(c) Percentage point drop

in return on investments 1% 2% 3%

(d) Drop in investment

income [(a) x (c)] $1,000 $2,000 $3,000

Total premium income

required to make up for

drop in investment income

[(b) + (d)] $26,000 $27,000 $28,000

Percentage increase in

premium income required

[(d) / (b) x 100] 4% 8% 12%

30

Insurers in states where it takes more time to resolve medical malpractice claims would be

more affected by changes in interest rates than insurers in states where it takes less time to

resolve claims.

Page 28 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

Downward Pressure on

Premium Rates Has

Decreased as Profitability

Has Declined

Since 1999, the profitability of the medical malpractice insurance market as

a whole has declined—even with increasing premium rates—causing some

large insurers to pull out of this market, either in certain states or

nationwide. Because fewer insurers are offering this insurance, there is less

price competition and thus less downward pressure on premium rates.

According to some industry and regulatory officials in our seven sample

states, price competition during most of the 1990s kept premium rates from

rising between 1992 and 1998, even though losses generally did rise. In

some cases, rates actually fell. For example, during this period premium

rates for obstetricians and gynecologists covered by the largest insurer in

Florida—a state where these physicians are currently seeing rapid

premium rate increases—actually decreased by approximately 3.1 percent.

Some industry participants we spoke with told us that, in hindsight,

premium rates charged by some insurers during this period may have been

lower than they should have been and, after 1998, began rising to a level

more in line with insurers’ losses on claims. Some industry participants

also pointed out that this pricing inadequacy was masked to some extent by

insurers’ adjustments to expected losses on claims reported during the late

1980s as well as their high investment income. For many insurers the

incurred losses associated with the policies sold during the late 1980s

turned out to be higher than the actual losses for the same policies,

resulting in high levels of reserves. During the 1990s, as insurers eliminated

these redundant reserves by adjusting their current loss reserves for these

previous overestimates, current calendar year incurred losses fell and

reported income increased. These adjustments, together with relatively

high levels of investment income, allowed insurers to keep premium rates

flat and still remain profitable.

Selling Medical Malpractice

Insurance Has Become Less

Profitable

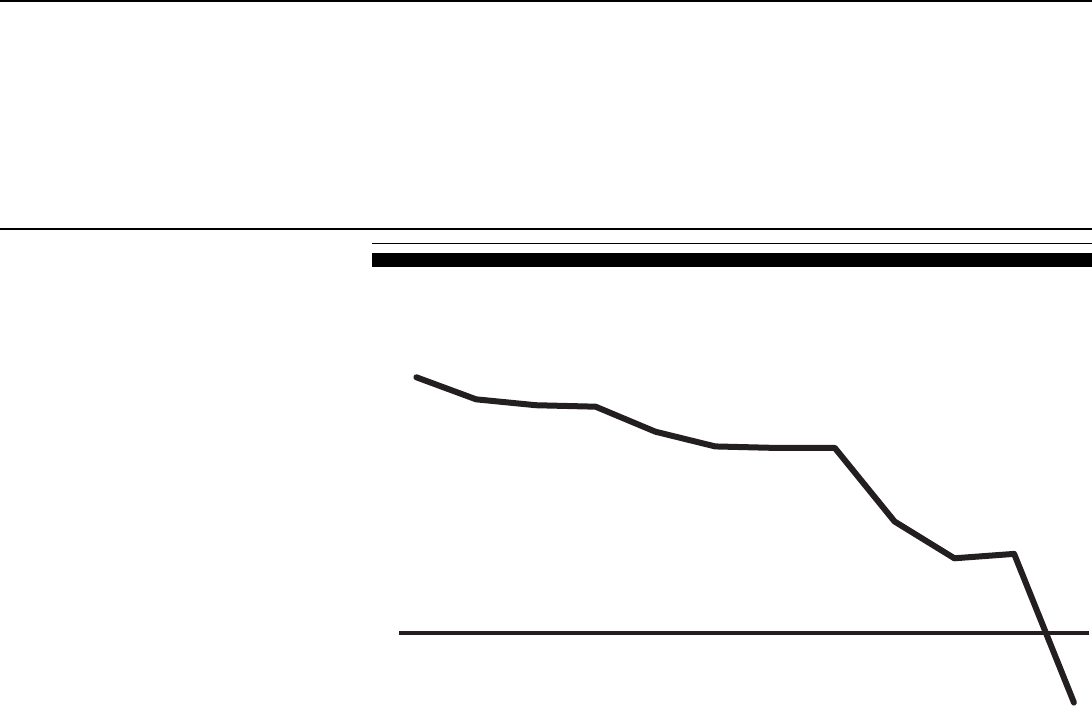

Beginning in the late 1990s, medical malpractice insurers as a whole began

to see their profits fall. Figure 7 shows the return on surplus—also called

return on equity—for the medical malpractice insurance industry as a

whole. Profitability began declining faster in 1998 and in 2001 dropped

considerably even as premium rates were increasing in many states,

resulting in a negative rate of return, or loss. Some of the factors pushing

premium rates upward were also factors in insurers’ declining profitability:

higher losses on medical malpractice claims, higher reinsurance costs, and

falling investment income.

Page 29 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

Figure 7: Net Profit or Loss as a Percentage of Net Worth for Medical Malpractice

Insurance Companies Nationwide, 1990–2001

Medical malpractice insurers in some of our sample states have

experienced particularly low levels of profitability since around 1998 (see

fig. 8). The loss ratio reported here is the ratio of incurred losses, not

including other expenses (often referred to as loss adjustment expenses)

related to resolving those claims, to the amount of premiums earned in a

given year. Loss ratios above 100 percent indicate that an insurer has

incurred more losses than premium payments, a sign of declining

profitability. Loss ratios in all seven sample states have increased since

1998, and except for California, all had loss ratios of more than 100 percent

for 2001.

Source: GAO analysis of NAIC data.

-5

0

5

10

15

20

200120001999199819971996199519941993199219911990

Percentage of net worth

17.4

15.9

15.5

15.4

13.7

12.7

12.6 12.6

7.6

5.1

5.4

-4.7

Page 30 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

Figure 8: Aggregate Incurred Losses as a Percentage of Premiums Earned for Medical Malpractice Insurers in Seven Selected

States, 1975–2001

Note: Incurred losses used in this figure do not include other expenses related to resolving claims or

loss adjustment expenses.

Source: GAO analysis of A.M. Best data.

Texas

Pennsylvania

Florida

California

Nevada

Mississippi

Minnesota

Percentage

0

50

100

150

200

200120001999199819971996199519941993199219911990198919881987198619851984198319821981198019791978197719761975

Percentage

-50

0

50

100

150

200

200120001999199819971996199519941993199219911990198919881987198619851984198319821981198019791978197719761975

Percentages above 100 indicate that

losses from medical malpractice claims

exceeded premiums for the year.

Percentages above 100 indicate that

losses from medical malpractice claims

exceeded premiums for the year.

Page 31 GAO-03-702 Medical Malpractice Insurance

As Profits Have Fallen, Insurers

Have Left the Medical

Malpractice Market

This declining profitability has caused some large insurers either to stop

selling medical malpractice policies altogether or to reduce the number

they sell. For example, beginning in 2002 the St. Paul Companies—

previously the second-largest medical malpractice insurer in the United

States—stopped writing all medical malpractice insurance because of

declining profitability. In 2001, St. Paul had sold medical malpractice

insurance in every state and was the largest or second-largest seller in 24

states. St. Paul was not alone. Other large insurers have also stopped

selling medical malpractice insurance in since 1999: PHICO Insurance

Company, which sold insurance primarily in six states, including Florida,

Pennsylvania, and Texas; MIIX Insurance Company, which sold insurance

primarily in five states, including New Jersey and Pennsylvania; and

Reciprocal of America, which sold insurance primarily in six states,

including Alabama, Mississippi, and Virginia. Other insurers reduced the

number of states in which they sold medical malpractice insurance: SCPIE

Indemnity Company, which in March 2003 essentially stopped selling

insurance outside of California, and First Professionals Insurance

Company, which has said that beginning in 2003 it will essentially stop

selling insurance outside of Florida.

When a large insurer leaves a state insurance market, the supply of medical

malpractice insurance decreases, and the remaining insurers may not need

to compete as much on the basis of price. In addition, the remaining

insurers are limited in the amount of insurance they can supply to fill the

gap, because state insurance regulations limit the amount of insurance they