FLOOD INSURANCE

FEMA's New Rate-

Setting Methodology

Improves Actuarial

Soundness but

Highlights Need for

Broader Program

Reform

Report to Congressional Addressees

July 2023

GAO-23-105977

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-23-105977, a report to

congressional

addressees

July 2023

FLOOD INSURANCE

FEMA’s New Rate

-Setting Methodology Improves

Actuarial Soundness

but Highlights Need

for Broader

Program

Reform

What GAO Found

In October 2021, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) began

implementing Risk Rating 2.0, a new methodology for setting premiums for the

National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). The new methodology substantially

improves ratemaking by aligning premiums with the flood risk of individual

properties, but some other aspects of NFIP still limit actuarial soundness. For

example, in addition to the premium, policyholders pay two charges that are not

risk based. Unless Congress authorizes FEMA to align these charges with a

property’s risk, the total amounts paid by policyholders may not be actuarially

justified, and some policyholders could be over- or underpaying. Further,

Congress does not have certain information on the actuarial soundness of NFIP,

such as the risk that the new premiums are designed to cover and projections of

fiscal outlook under a variety of scenarios. By producing an annual actuarial

report that includes these items, FEMA could improve understanding of Risk

Rating 2.0 and facilitate congressional oversight of NFIP.

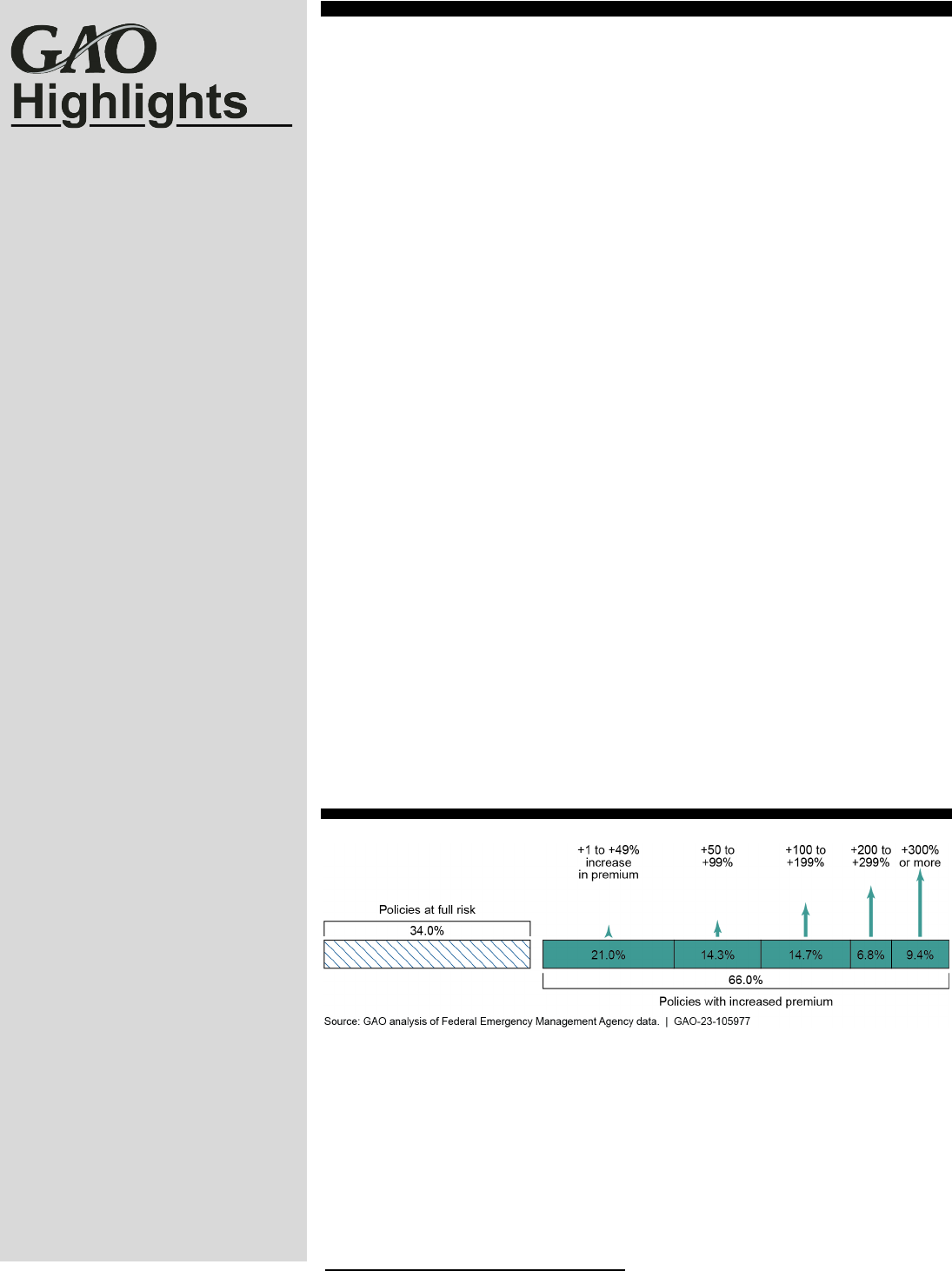

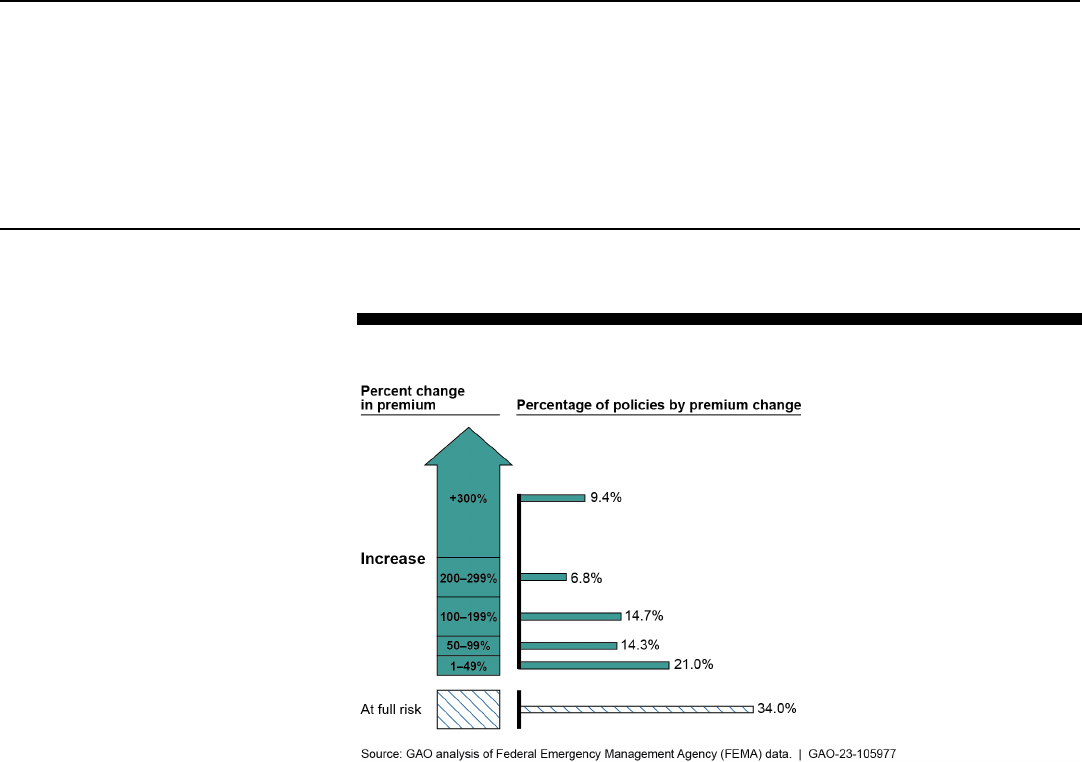

Risk Rating 2.0 is aligning premiums with risk, but affordability concerns

accompany the premium increases. FEMA had been increasing premiums for a

number of years prior to implementing Risk Rating 2.0. By December 2022, the

median annual premium was $689, but this will need to increase to $1,288 to

reach full risk. Under Risk Rating 2.0, about one-third of policyholders are

already paying full-risk premiums. Many of these policyholders had their

premiums reduced upon implementation of Risk Rating 2.0. All others will require

higher premiums, including 9 percent who will eventually require increases of

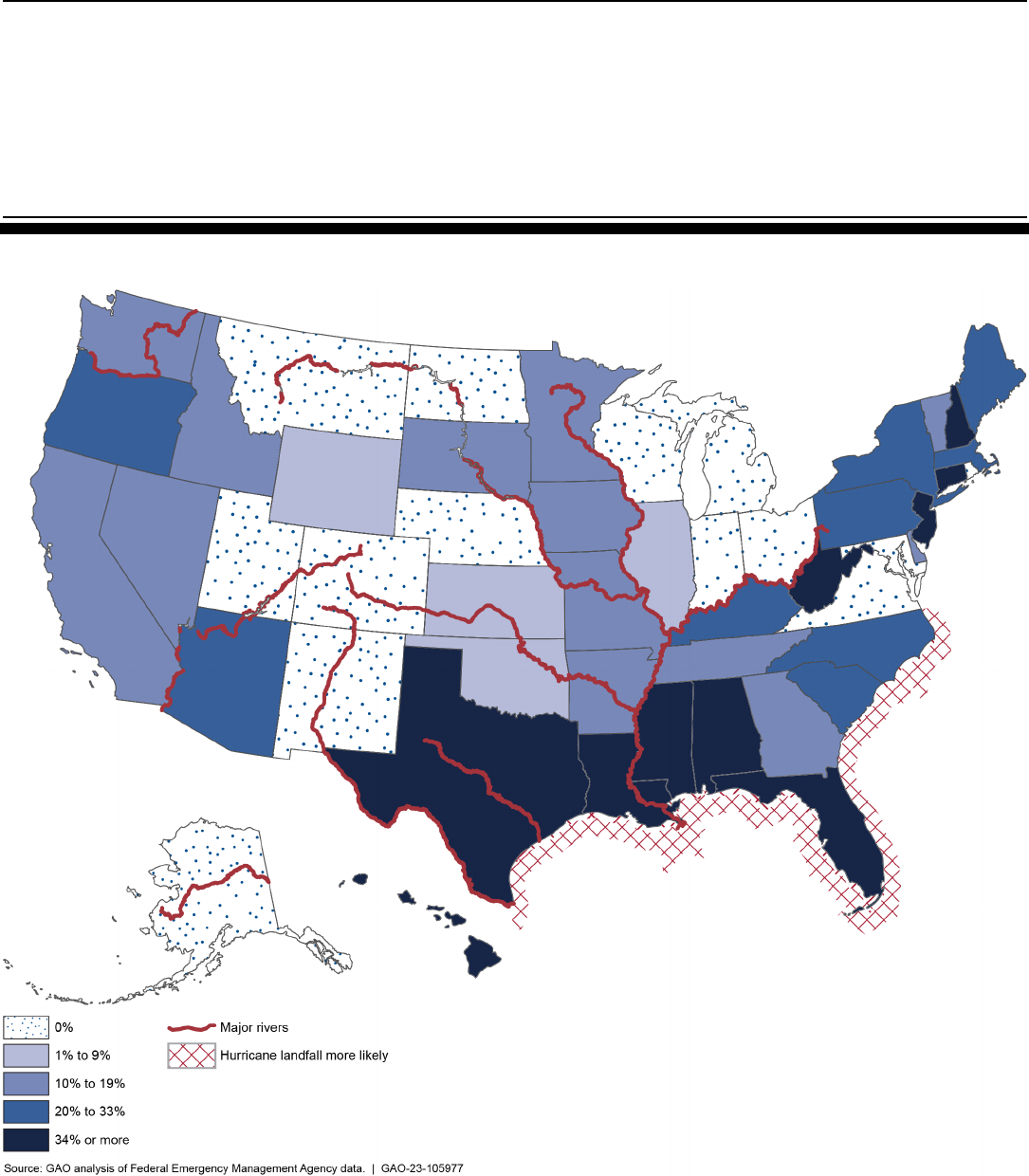

more than 300 percent. Further, Gulf Coast states are among those experiencing

the largest premium increases. Policies in these states have been among the

most underpriced, despite having some of the highest flood risks.

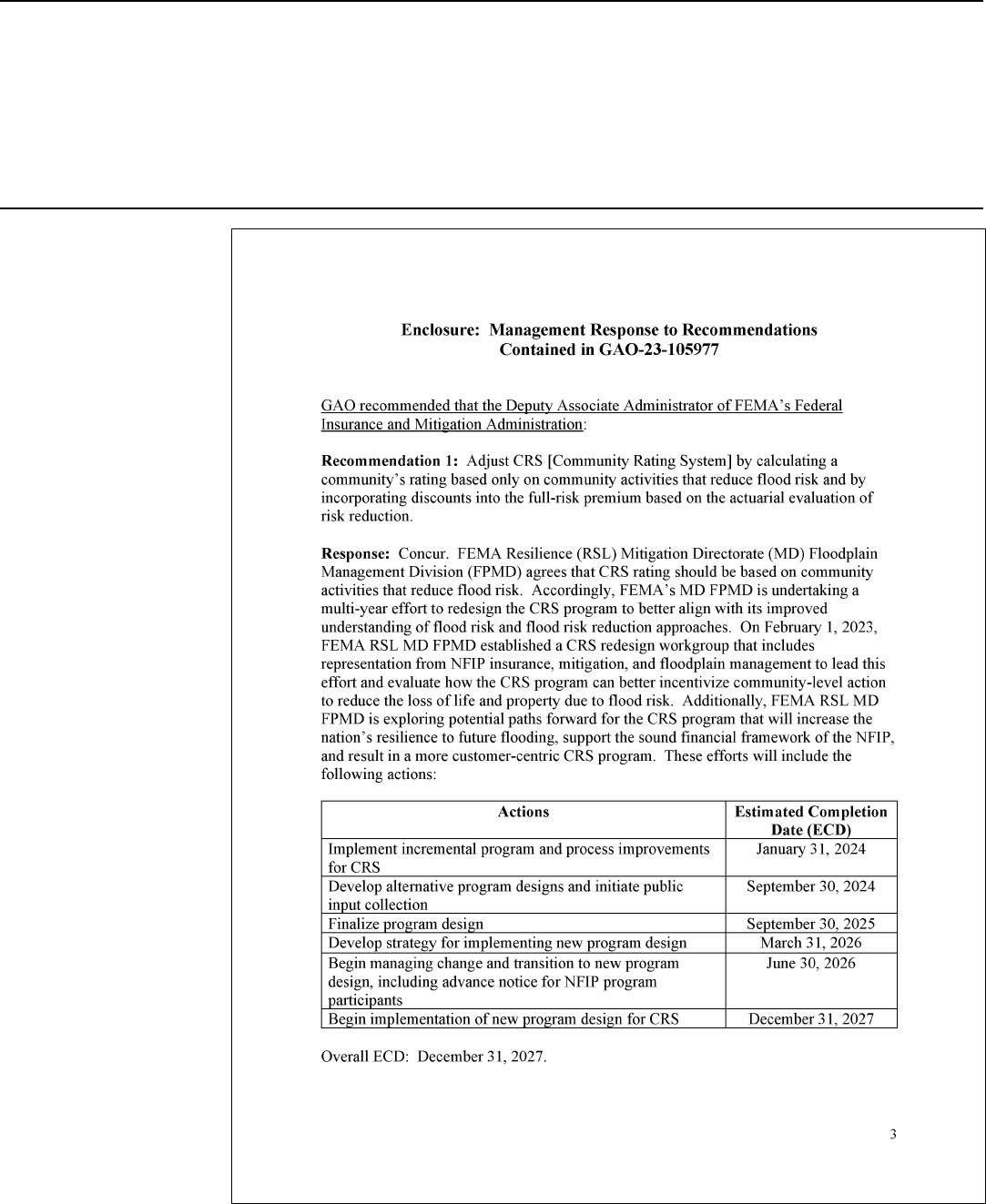

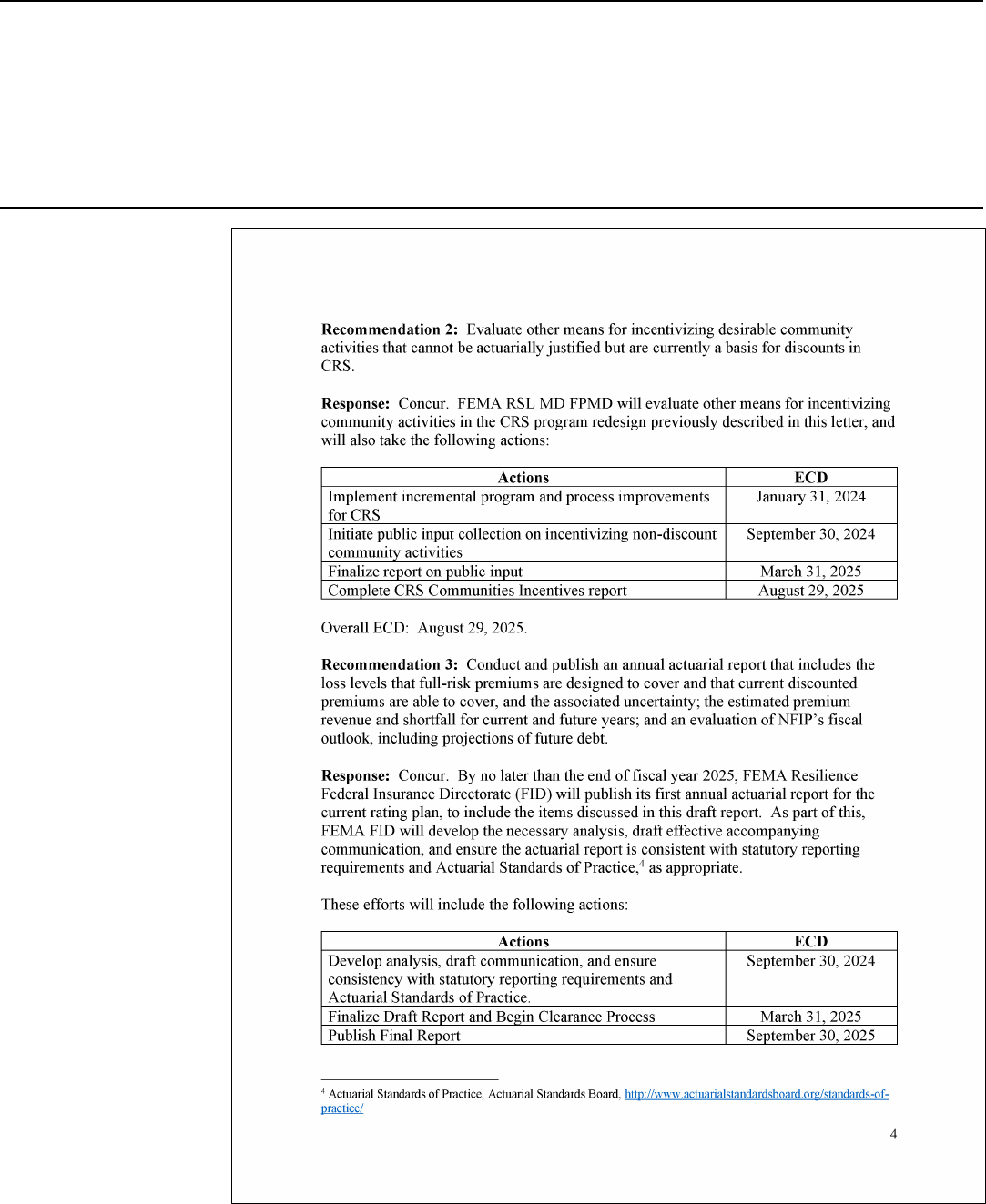

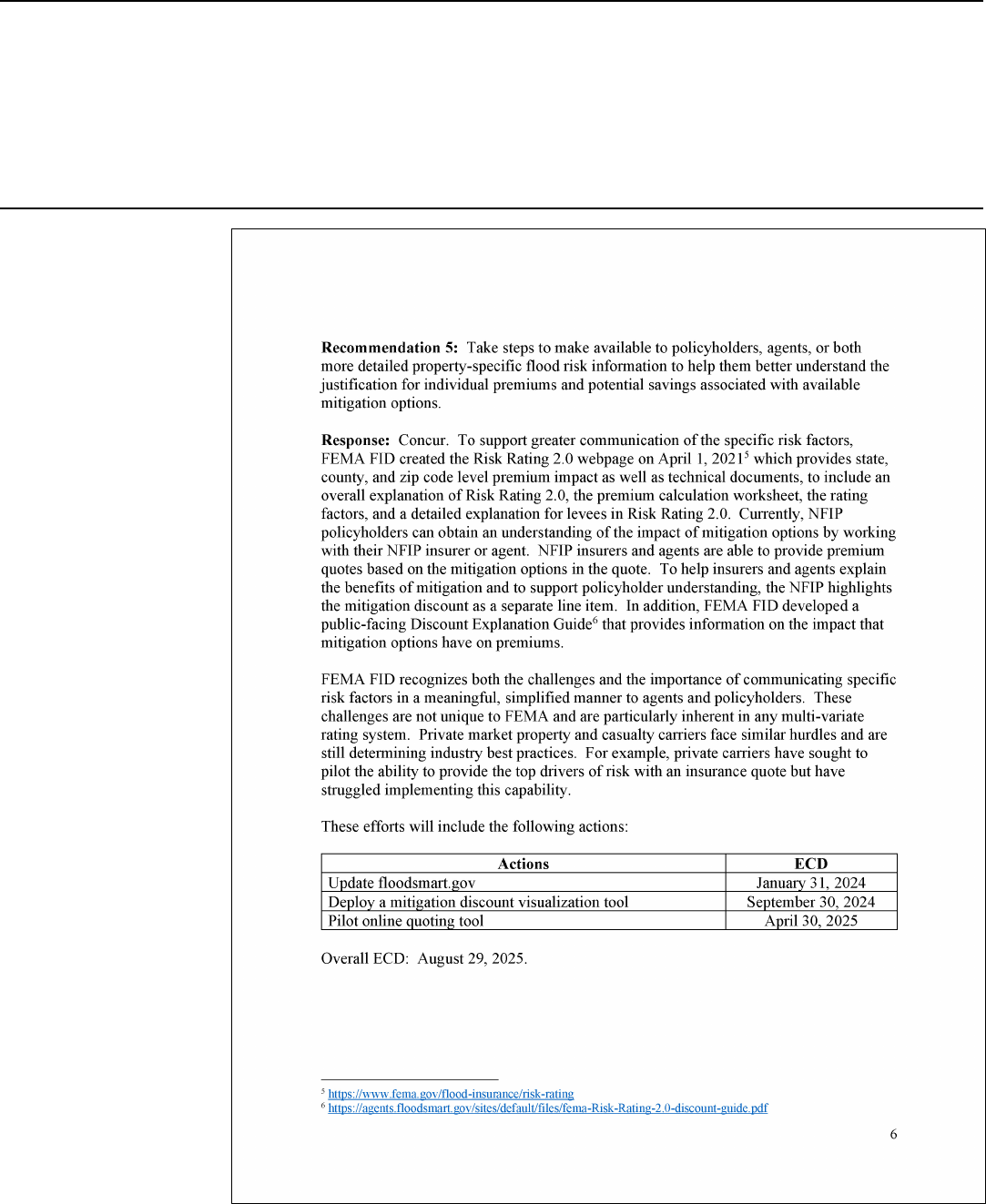

Estimated Premium Changes under Risk Rating 2.0, as of December 2022

Annual premium increases for most policyholders are limited to 18 percent by

statute. These caps help address some affordability concerns in the near term,

but have several limitations.

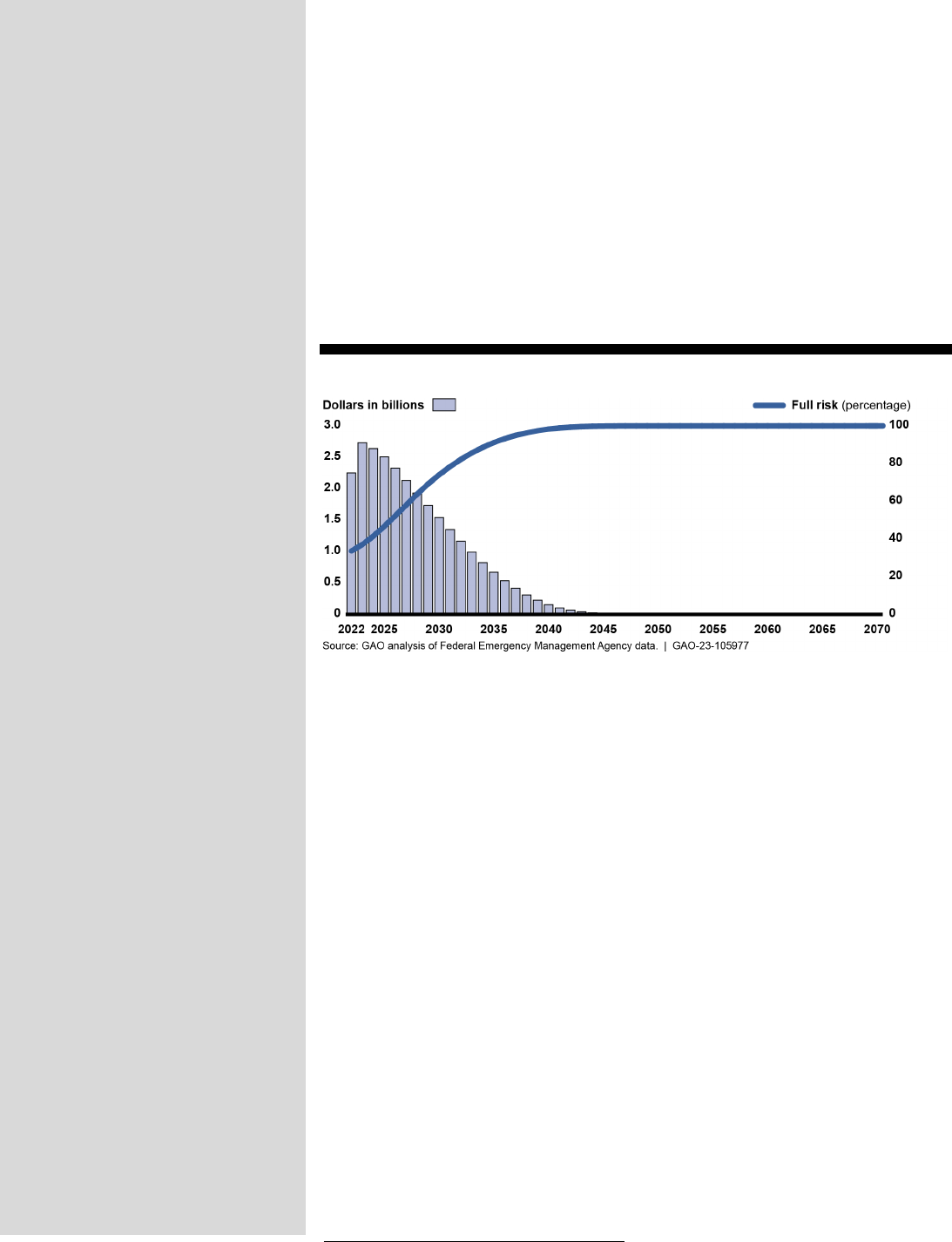

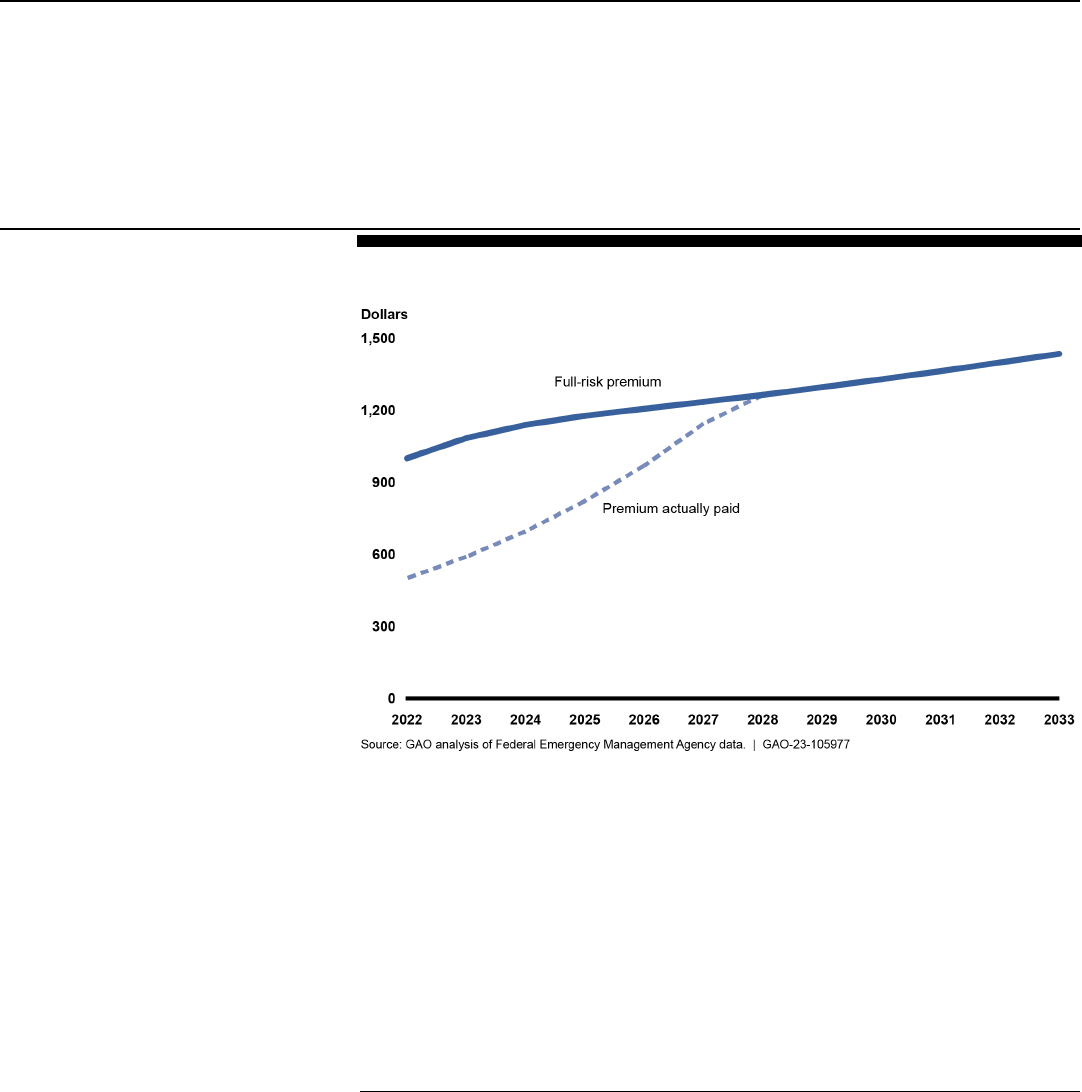

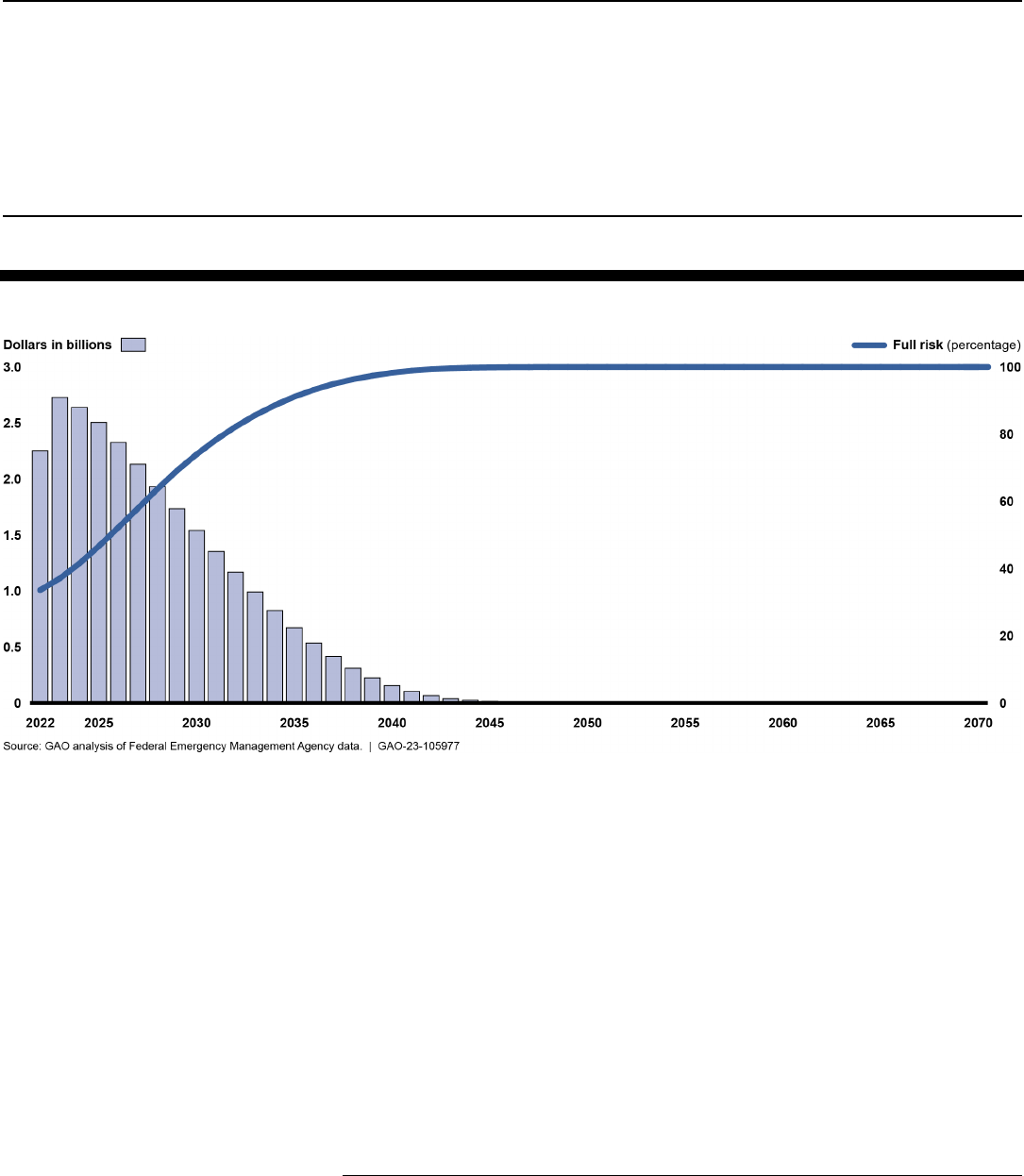

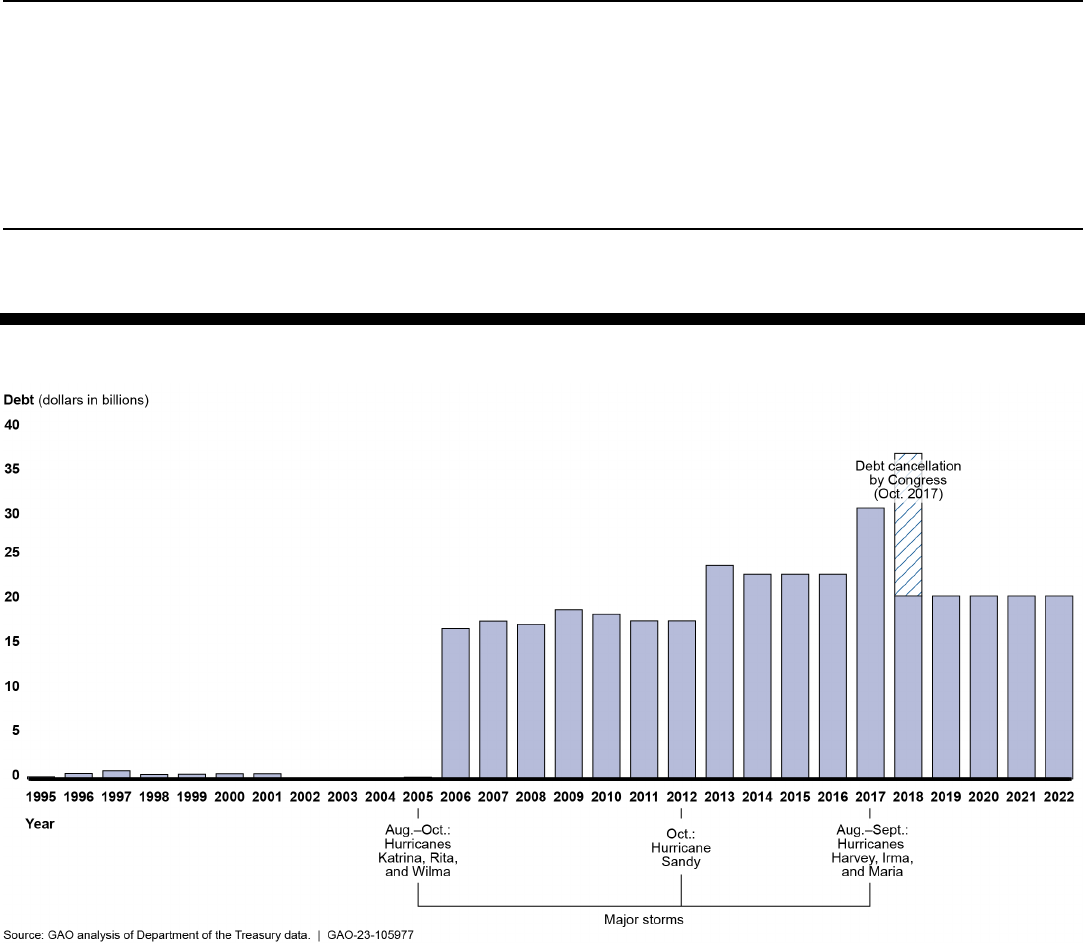

• First, the caps perpetuate an unfunded premium shortfall. GAO

estimated it would take until 2037 for 95 percent of current policies to

reach full-risk premiums, resulting in a $27 billion premium shortfall (see

figure below). The costs of shortfalls are not transparent to Congress or

the public because they are not recognized in the federal budget and

become evident only when NFIP must borrow from the Department of

the Treasury after a catastrophic flood event.

View GAO-23-105977. For more information,

contact

Alicia Puente Cackley at (202) 512-

8678 or

[email protected] or Frank Todisco

at (202) 512

-2700 or todiscof@gao.gov.

Why GAO Did This Study

NFIP was created with competing

policy goals

—keeping flood insurance

affordable and the program fiscally

solvent. A historical focus on

affordability has led to premiums that

do not fully reflect

flood risk,

insufficient

revenue

to pay claims, and, ultimately,

$36.5 billion in borrowing from

Treasury since 2005.

FEMA

’s new Risk Rating 2.0

methodology is intended to better align

premium

s with underlying flood risk at

the individual property level.

This report

examines several

objectives,

including (1) the actuarial

soundness of

Risk Rating 2.0, (2) how

premium

s are changing, (3) efforts to

address affordability for policyholders,

(4)

options for addressing the debt,

and (5) implications for the private

market

.

GAO reviewed

FEMA documentation

and analyzed NFIP

, Census Bureau,

and private flood

insurance data. GAO

also interviewed FEMA officials

,

actuarial organizations, private flood

insurers, and insurance agent

association

s.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends

six matters for

congressional consideration

.

Specifically, Congress should consider

the following:

•

Authorizing and requiring

FEMA to

replace two policyholder charges

with risk-based premium charges

•

Replacing discounted premiums

with a means-based assistance

program that is reflected in the

federal budget

United States Government Accountability Office

• Second, the caps address affordability poorly. For example, they are not

cost-effective because some policyholders who do not need assistance

likely are still receiving it. Concurrently, some policyholders needing

assistance likely are not receiving it, and the discounts will gradually

disappear as premiums transition to full risk.

• Third, the caps keep NFIP premiums artificially low, which undercuts

private-market premiums and hinders private-market growth.

An alternative to caps on annual premium increases is a means-based

assistance program that would provide financial assistance to policyholders

based on their ability to pay and be reflected in the federal budget. Such a

program would make NFIP’s costs transparent and avoid undercutting the private

market. If affordability needs are not addressed effectively, more policyholders

could drop coverage, leaving them unprotected from flood risk and more reliant

on federal disaster assistance. Addressing affordability needs is especially

important as actions to better align premiums with a property’s risk could result in

additional premium increases.

Estimated Premium Shortfall and Percentage of National Flood Insurance Program Policies at

Full-Risk Premiums, by Calendar Year

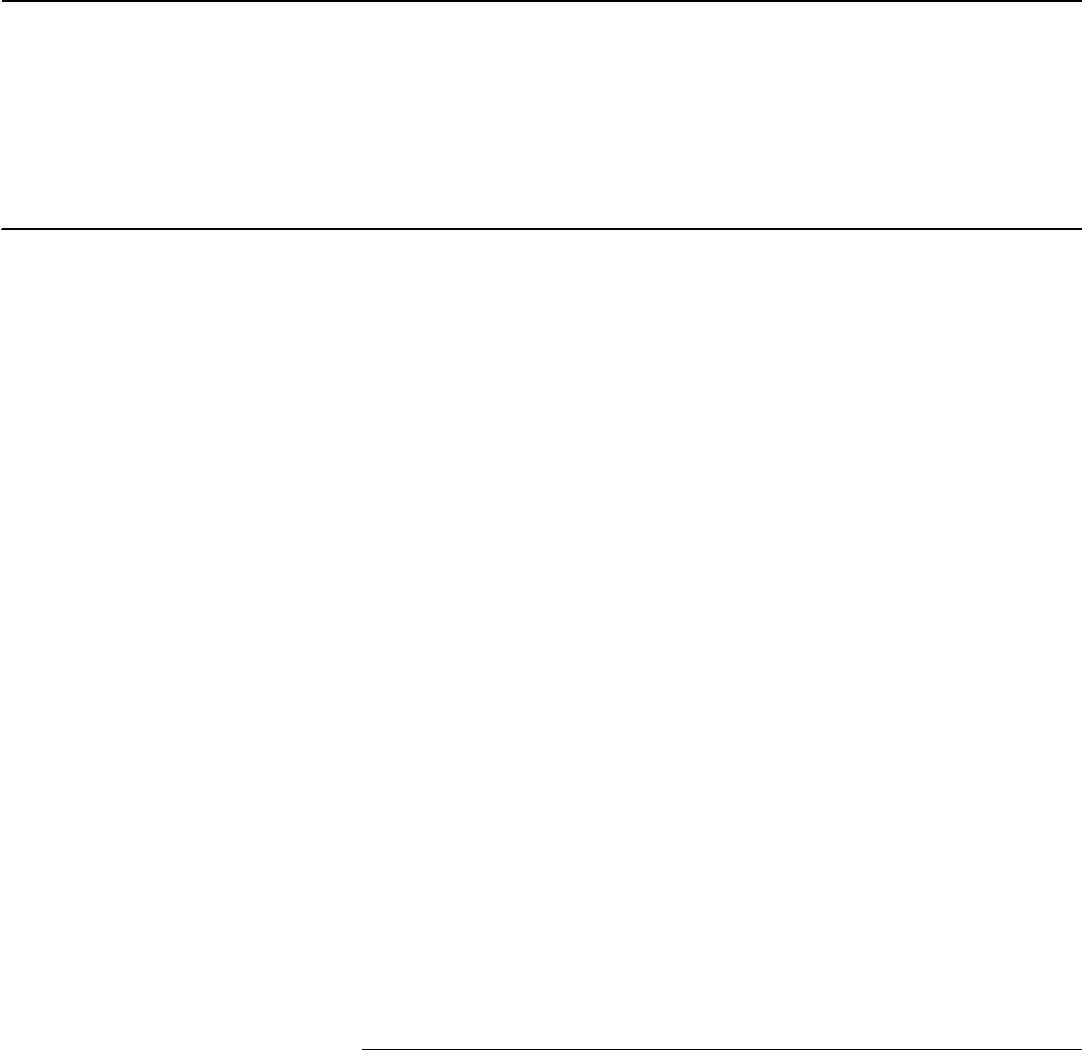

FEMA has had to borrow from Treasury to pay claims in previous years and

would have to use revenue from current and future policyholders to repay the

debt. NFIP’s debt largely is a result of discounted premiums that FEMA has been

statutorily required to provide. In addition, a statutorily-required assessment has

the effect of charging current and future policyholders for previously incurred

losses, which violates actuarial principles and exacerbates affordability concerns.

Even with this assessment, it is unlikely that FEMA will ever be able to repay the

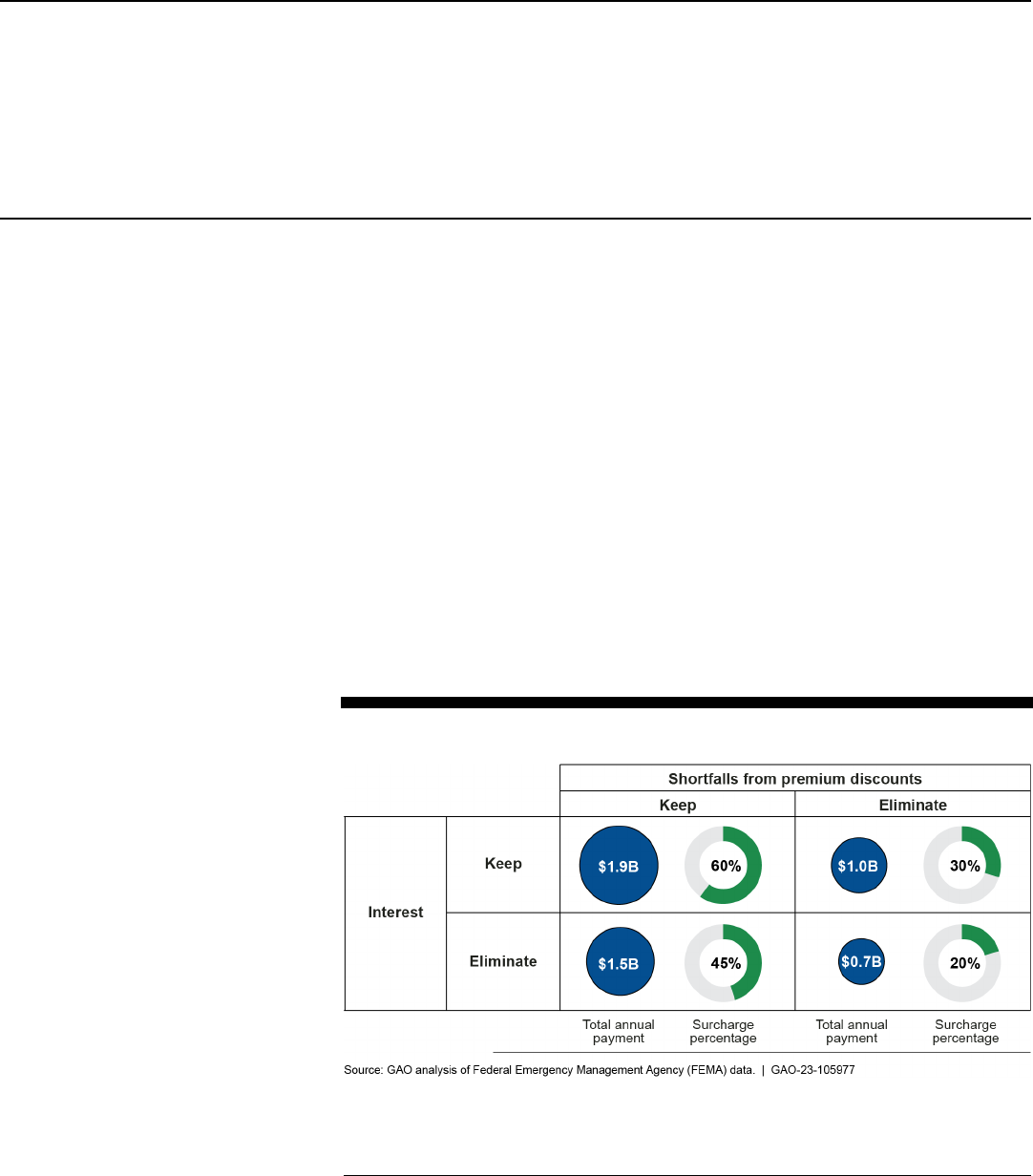

debt as currently structured. For example, with the estimated premium shortfalls,

repaying the debt in 30 years at 2.5 percent interest would require an annual

payment of about $1.9 billion, equivalent to a 60 percent surcharge for each

policyholder in the first year. Such a surcharge could cause some policyholders

to drop coverage, leaving them unprotected from flood risk and leaving NFIP with

fewer policyholders to repay the debt. Unless Congress addresses this debt—for

example, by canceling it or modifying repayment terms—and the potential for

future debt, NFIP’s debt will continue to grow, actuarial soundness will be

delayed, and affordability concerns will increase.

Risk Rating 2.0 does not yet appear to have significantly changed conditions in

the private flood insurance market because NFIP premiums generally remain

lower than what a private insurer would need to charge to be profitable. Further,

certain program rules continue to impede private-market growth. Specifically,

NFIP policyholders are discouraged from seeking private coverage because

statute requires them to maintain continuous coverage with NFIP to have access

to discounted premiums, and they do not receive refunds for early cancellations if

they switch to a private policy. By authorizing FEMA to allow private coverage to

satisfy NFIP’s continuous coverage requirements and to offer risk-based partial

refunds for midterm cancellations replaced by private policies, Congress could

promote private-market growth and help to expand consumer options.

•

Addressing NFIP’s current debt—

for example, by canceling it or

modifying repayment terms—and

potential for future debt

• Authorizing and requiring FEMA to

revise NFIP rules hindering the

private market related to (1)

continuous coverage and (2)

partial refunds for midterm

cancellations

GAO is also making five

recommendatons to FEMA, including

that it publish an annual report on

NFIP’s actuarial soundness and fiscal

outlook. The Department of Homeland

Security agreed with the

recommendations.

View GAO-23-105977. For more information,

contact

Alicia Puente Cackley at (202) 512-

8678 or

[email protected] or Frank Todisco

at (202) 512

-2700 or todiscof@gao.gov.

Page i GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

Letter 1

Background 4

Risk Rating 2.0 Significantly Improves Ratemaking, but Certain

Aspects of NFIP Limit Actuarial Soundness 12

Risk Rating 2.0 Is Aligning Premiums with Risks, but Some

Policyholders Face Increasing Affordability Concerns 23

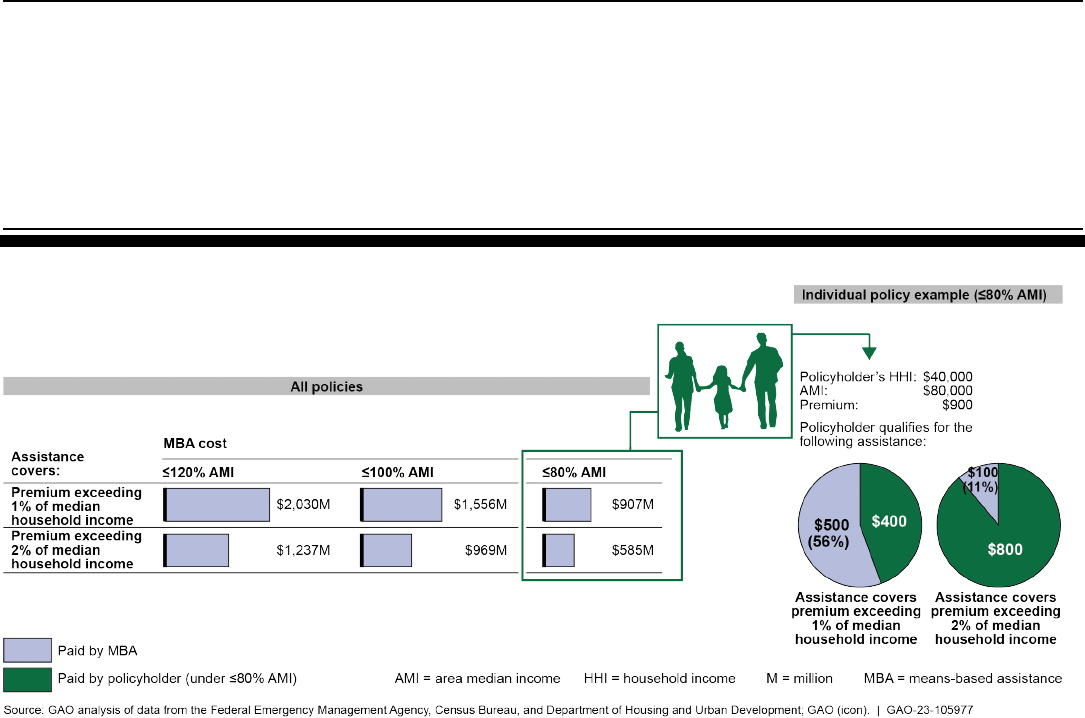

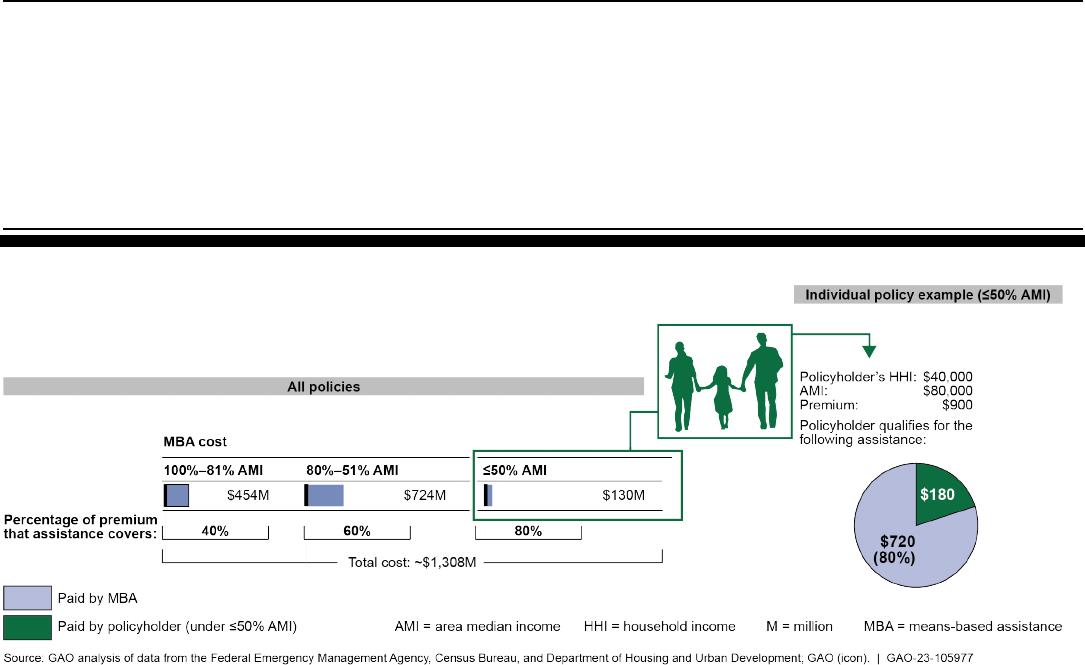

Means-Based Assistance Could Address Affordability More

Transparently and Efficiently Than Discounted Premiums 34

Options Exist to Address NFIP’s Legacy Debt and the Potential for

Future Debt 47

Risk Rating 2.0 Has Not Yet Significantly Affected the Private

Insurance Market, but Some NFIP Rules Hinder Market Growth 56

FEMA Has Released Detailed Information on Risk Rating 2.0, but

Has Not Provided It to Policyholders 60

Conclusions 62

Matters for Congressional Consideration 65

Recommendations for Executive Action 66

Agency Comments 67

Appendix I Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 69

Appendix II Additional Data on Glidepath and Means-Based Assistance

Estimates 76

Appendix III Comments from the Department of Homeland Security 78

Appendix IV GAO Contacts and Staff Acknowledgments 84

Tables

Table 1: National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) Policyholder

Assessments, Surcharges, and Fees 8

Table 2: Estimated Median National Flood Insurance Program

(NFIP) Premiums, by Race and Ethnicity 32

Table 3: Glidepath Time and Premium Shortfall Estimates 76

Contents

Page ii GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

Table 4: Estimated Participants and Costs of Alternative Means-

Based Assistance Programs 77

Figures

Figure 1: Policyholder Costs for a Hypothetical National Flood

Insurance Program Policy 10

Figure 2: National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) Flow of Funds 11

Figure 3: Estimated Future Premium Changes under Risk Rating

2.0, as of December 2022 25

Figure 4: Median Percent Change from Legacy NFIP Premium to

Full-Risk Premium under Risk Rating 2.0, by State, as of

December 31, 2022 27

Figure 5: Median NFIP Premium, by State, as of December 31,

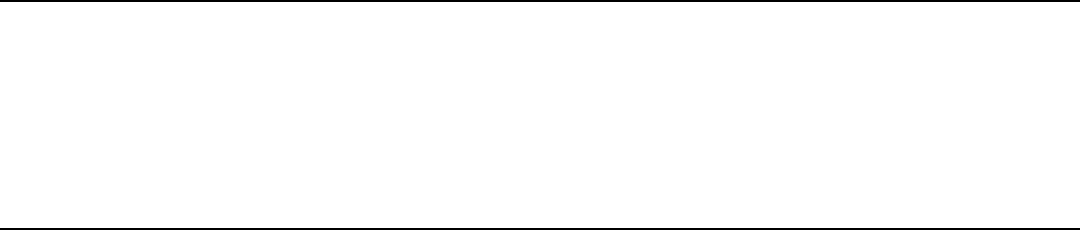

2022 29

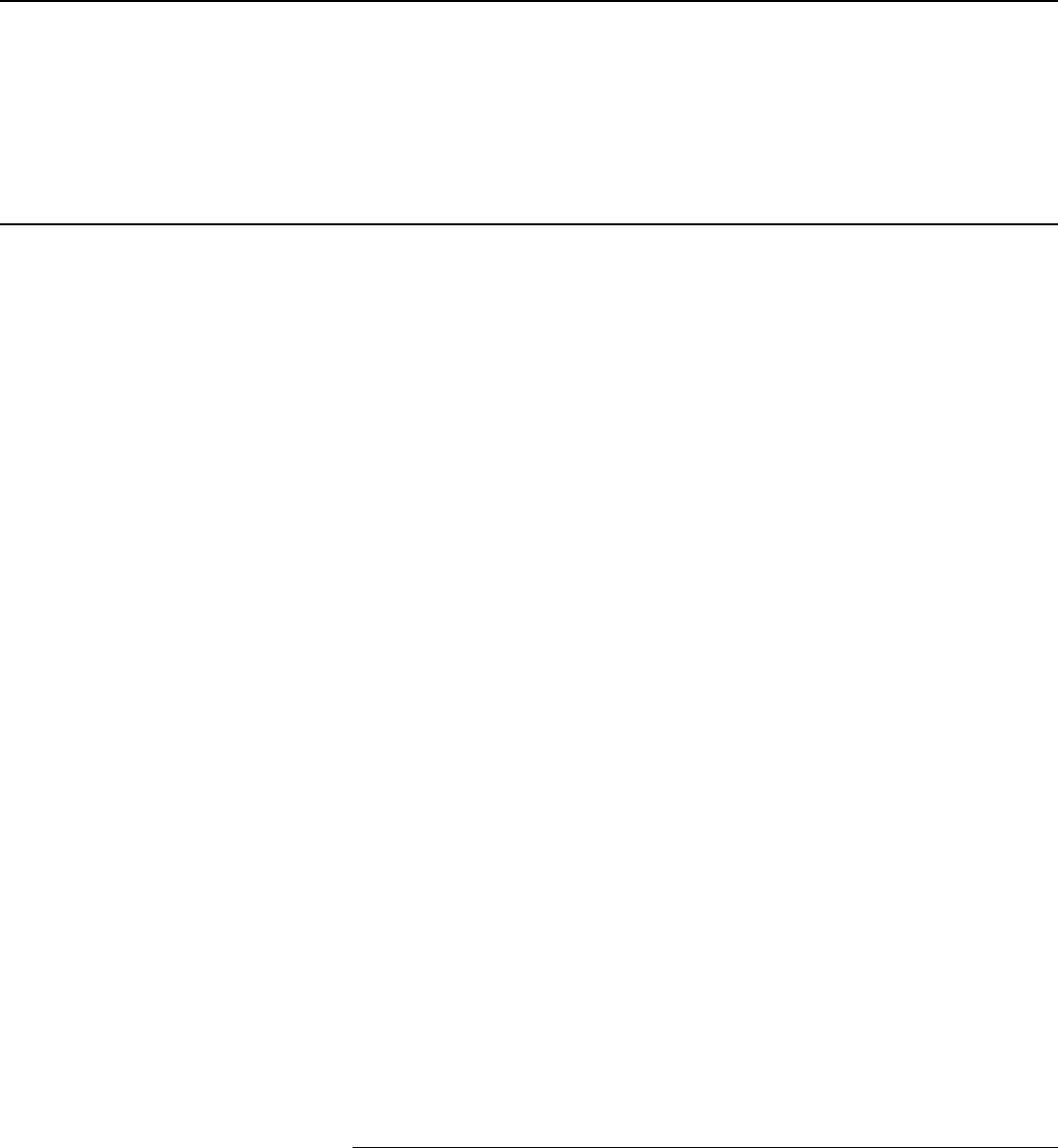

Figure 6: Median Full-Risk NFIP Premiums as a Percentage of

Household Income, by State, as of December 31, 2022 31

Figure 7: Affordability of National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP)

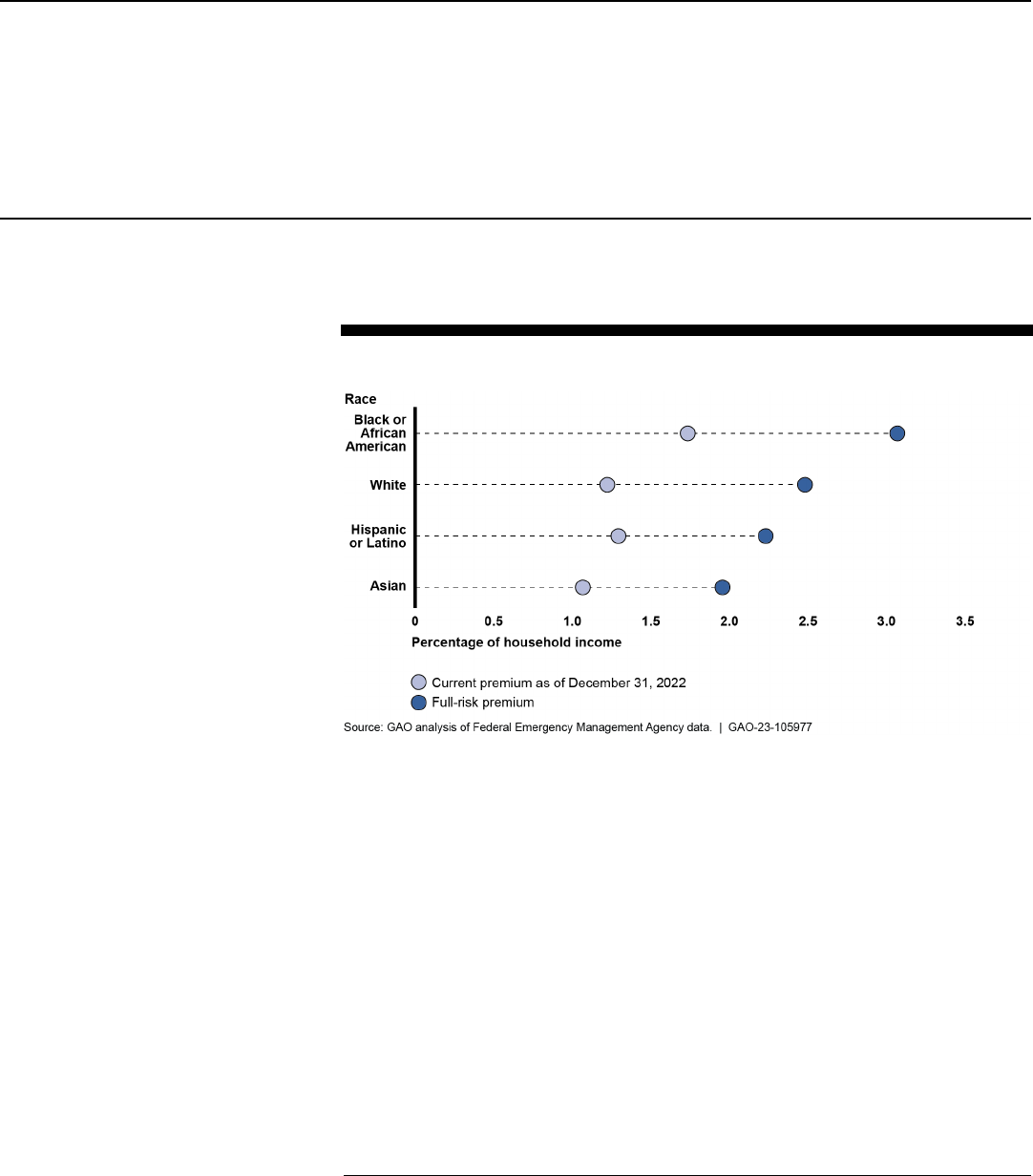

Premiums, by Race and Ethnicity 33

Figure 8: Illustration of the Premium Shortfall and Transition to

Full-Risk Premium for a Hypothetical National Flood

Insurance Program Policy 35

Figure 9: Estimated Premium Shortfall and Percentage of National

Flood Insurance Program Policies at Full-Risk Premiums,

by Calendar Year 36

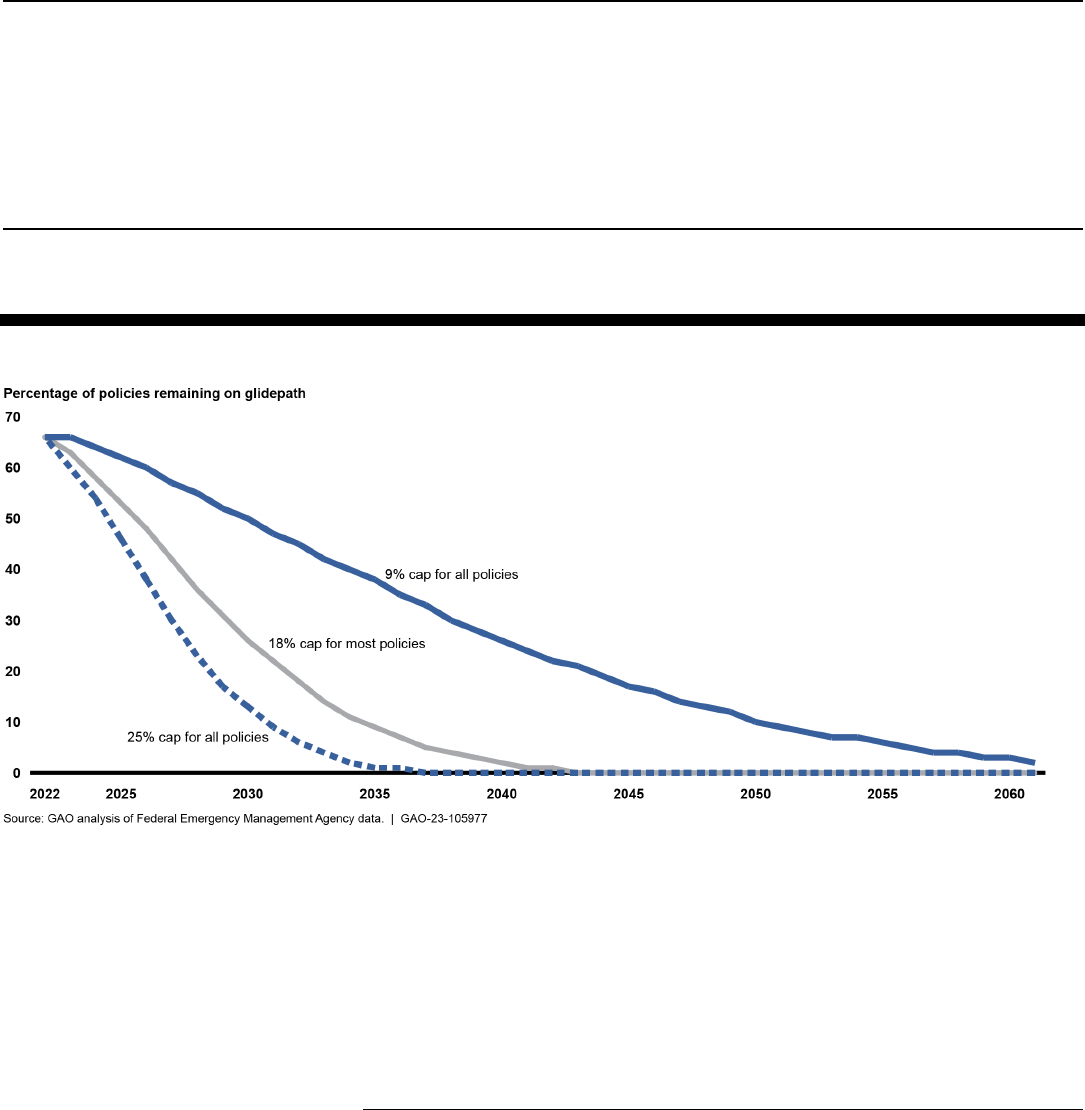

Figure 10: National Flood Insurance Program Policies Remaining

on the Glidepath under Alternative Annual Premium

Increase Caps, by Year 37

Figure 11: Cost Estimates of a Means-Based Assistance

Program—Alternative 1 42

Figure 12: Cost Estimates of a Means-Based Assistance

Program—Alternative 2 43

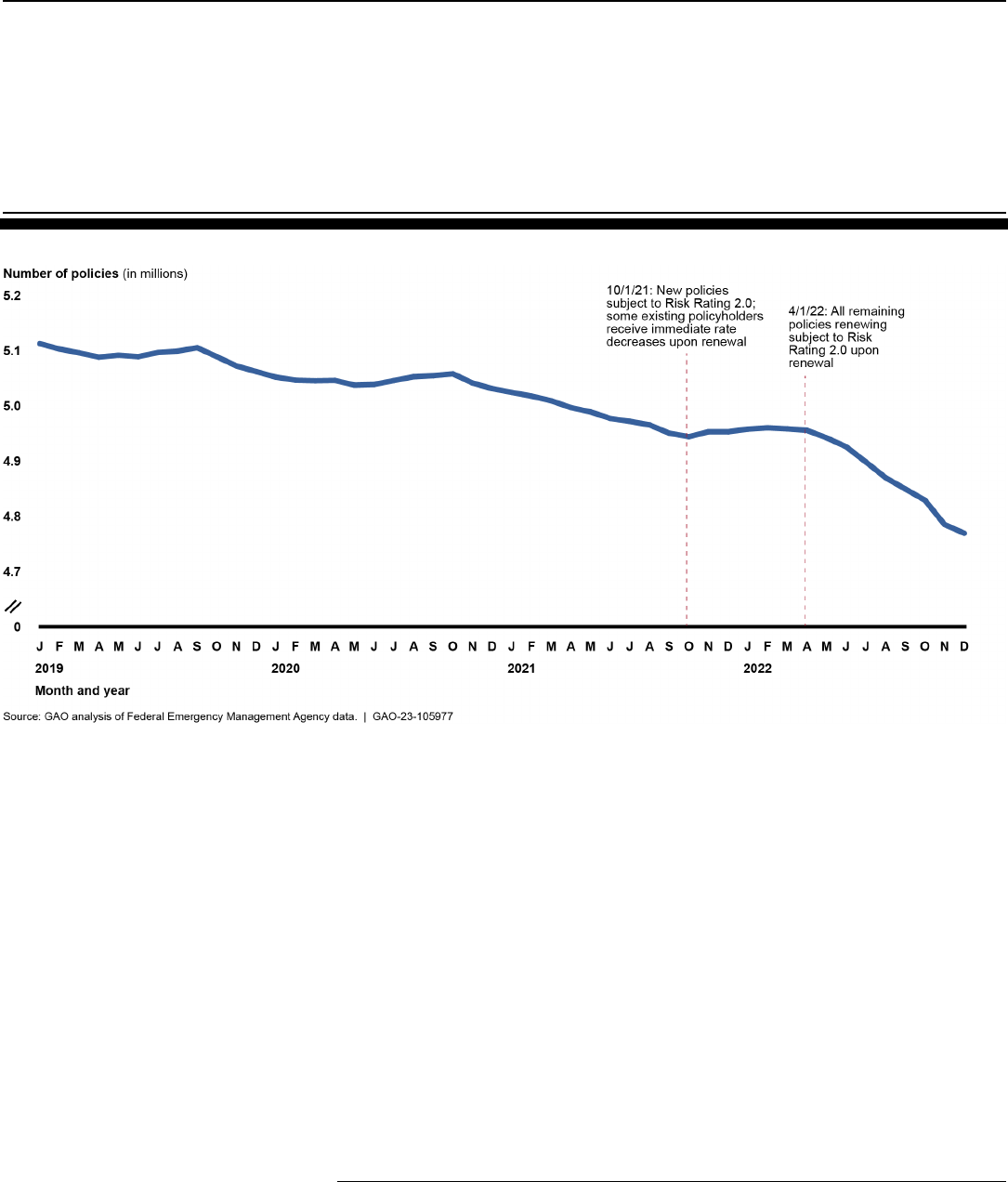

Figure 13: Number of National Flood Insurance Program Policies,

2019–2022 46

Figure 14: National Flood Insurance Program Annual Year-End

Outstanding Debt to the Department of the Treasury,

Fiscal Years 1995–2022 48

Figure 15: Estimated Effects of Various Requirements for

Repaying National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) Debt

over 30 Years 52

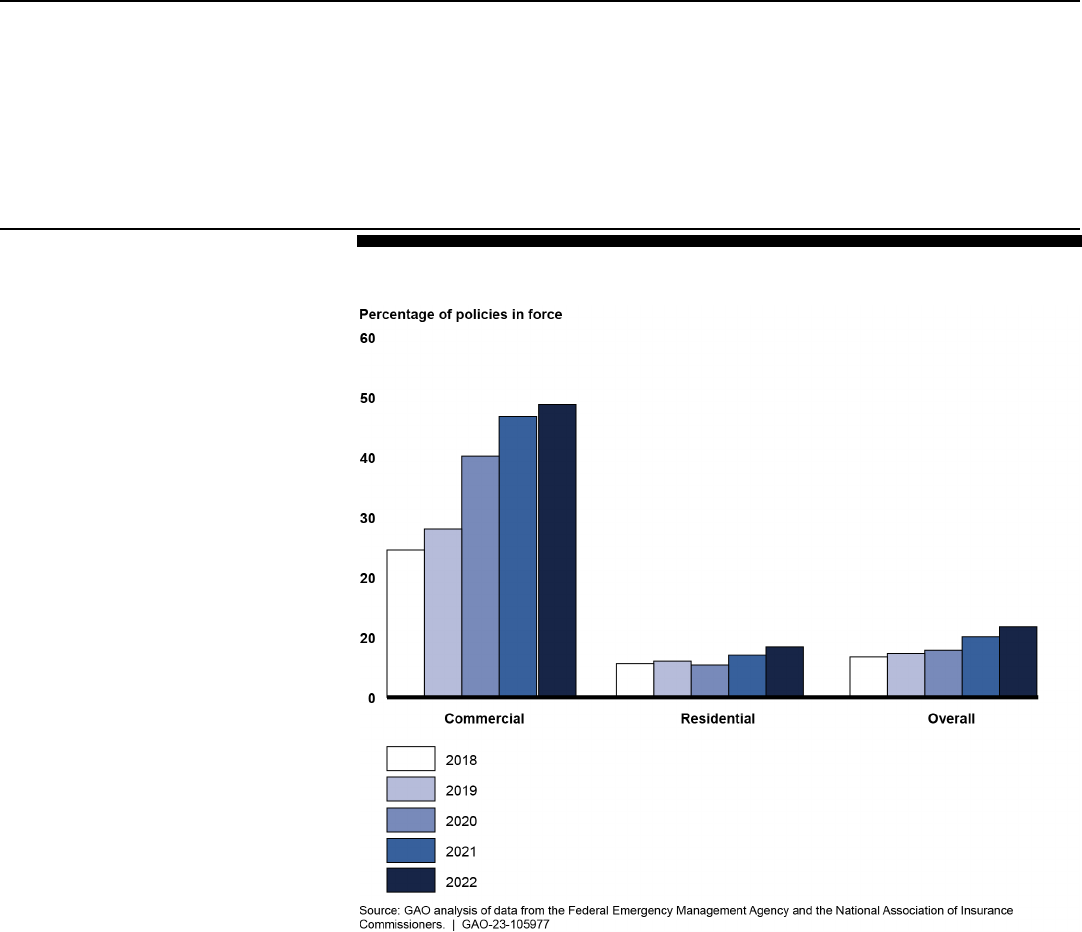

Figure 16: Private Flood Insurance Share of Flood Insurance

Policies, by Number of Policies 57

Page iii GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

Abbreviations

AMI area median income

BISG Bayesian Improved Surname Geocoding

CRS Community Rating System

FEMA Federal Emergency Management Agency

FIRM Flood Insurance Rate Map

HFIAA Homeowner Flood Insurance Affordability Act of 2014

HHI household income

MBA means-based assistance

NAIC National Association of Insurance Commissioners

NFIP National Flood Insurance Program

SFHA special flood hazard area

WYO Write Your Own

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

July 31, 2023

The Honorable Sherrod Brown

Chairman

The Honorable Tim Scott

Ranking Member

Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Patrick McHenry

Chairman

The Honorable Maxine Waters

Ranking Member

Committee on Financial Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Bennie G. Thompson

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable Troy Carter

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Emergency Management and Technology

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) has competing policy

objectives: being fiscally solvent while keeping flood insurance affordable

for policyholders. Balancing these objectives has been challenging over

the years, and a historical focus on affordability has come at the expense

of solvency. In particular, Congress has required the Federal Emergency

Management Agency (FEMA) to allow many policyholders to pay

discounted premiums that do not fully reflect their properties’ flood risk.

This approach has contributed to a shortfall in revenue and insufficient

funds to pay claims, causing FEMA to borrow about $36.5 billion from the

Letter

Page 2 GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

Department of the Treasury since 2005. For these reasons, we placed

NFIP on our High-Risk List in 2006.

1

The ratemaking methodology used until recently by FEMA has

contributed to these challenges.

2

This legacy methodology had become

outdated, as it had remained largely unchanged since NFIP was created

in 1968. To modernize its ratemaking methodology and better align

premiums with underlying flood risk at the individual property level, FEMA

developed a new methodology called Risk Rating 2.0 and began

implementing it in October 2021. Under Risk Rating 2.0, most

policyholders will continue to experience premium increases.

3

While

these increases will help move NFIP toward fiscal solvency and more

accurately signal to homeowners the flood risk of their property, they will

also amplify affordability concerns.

In April 2017, we outlined a road map for comprehensive reform that,

among other things, addresses the trade-offs between solvency and

affordability.

4

Since September 2017, NFIP has been operating under a

series of short-term reauthorizations without comprehensive reform. In

September 2023, NFIP’s current authorization will expire.

We performed our work under the authority of the Comptroller General in

light of congressional interest in FEMA’s new ratemaking methodology

and NFIP’s impending reauthorization. This report examines (1) the

actuarial soundness of the new methodology, (2) how premiums are

changing for policyholders, (3) efforts to make flood insurance affordable

for policyholders, (4) options for addressing program debt, (5) the

potential implications of Risk Rating 2.0 for the private flood insurance

market, and (6) FEMA’s efforts to promote policyholder understanding of

Risk Rating 2.0.

1

GAO, High Risk: Efforts Made to Achieve Progress Need to Be Maintained and

Expanded to Fully Address All Areas, GAO-23-106203 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 20, 2023).

2

Ratemaking is the process used to determine what prices (premiums) an insurer

charges.

3

Under the previous methodology, policyholders did not experience premium decreases.

However, under Risk Rating 2.0, about 19 percent of policyholders experienced an

immediate decrease in premiums.

4

GAO, Flood Insurance: Comprehensive Reform Could Improve Solvency and Enhance

Resilience, GAO-17-425 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 27, 2017).

Page 3 GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

To examine the actuarial soundness of Risk Rating 2.0, we reviewed

FEMA documentation and actuarial assumptions and methods used to

develop premiums. We also reviewed the premiums, assessments,

surcharges, and fees that policyholders pay and the costs these charges

are designed to cover. Finally, we interviewed FEMA officials and an

actuarial association and compared the methodology and results against

actuarial standards and principles.

To examine how premiums are changing for policyholders, we analyzed

NFIP policy data and Census Bureau data by geography and household

income.

5

We also used a statistical technique to estimate the probability

that NFIP policyholders identify as a particular race or ethnicity and

analyzed premium changes by these factors.

6

To examine efforts to make insurance affordable for policyholders, we

reviewed legislative proposals as well as policy goals established in our

prior work.

7

We analyzed NFIP policy data to estimate the time it might

take for FEMA to transition current policyholders to full-risk premiums and

the continued federal cost until the transition is completed. We accounted

for annual premium increase caps, inflation rates, flood risk, and NFIP

policy renewal, and we analyzed alternate scenarios for each of these

assumptions to determine how our estimates might change. We also

analyzed NFIP policy data and census data to estimate the potential

costs associated with providing means-based affordability assistance for

flood insurance.

To examine options for addressing program debt, we analyzed NFIP

policy data and reviewed our previous work on NFIP, as well as reports

from the Congressional Budget Office, Congressional Research Service,

5

We assessed the reliability of NFIP data we analyzed by reviewing relevant

documentation; testing the data to identify missing data, outliers, and any obvious errors;

and comparing our results to published data. We also interviewed FEMA officials and

reviewed relevant documentation. We determined that the NFIP data we analyzed were

sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our report.

6

We assessed the reliability of these estimates by conducting a literature review on the

accuracy of the technique and by examining the completeness and distributions of the

estimates for NFIP policyholders. We determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for

estimating the race or ethnicity of NFIP policyholders.

7

See GAO-17-425.

Page 4 GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

FEMA, and others. We assessed the options against actuarial standards

as well as policy goals we established in prior work.

To examine the potential implications of Risk Rating 2.0 for the private

flood insurance market, we analyzed NFIP policy data and data from the

National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) on private flood

insurance.

8

We also interviewed private insurers and reviewed laws and

regulations that affect private insurers’ ability to provide flood insurance.

We assessed these laws and regulations against policy goals we

established in prior work.

To examine FEMA’s efforts to promote policyholder understanding of Risk

Rating 2.0, we reviewed NFIP policy documents, FEMA’s web materials,

and training materials for agents and Write Your Own (WYO) insurers.

9

We also interviewed FEMA officials and insurance agent associations.

We compared this information against FEMA’s strategic plan. A more

detailed description of our scope and methodology is included in

appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from March 2022 to July 2023 in

accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain

sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our

findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that

the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Congress first proposed providing flood insurance in the 1950s, after it

became clear that private insurance companies could not profitably

provide flood coverage. Specifically, limited knowledge of flood risk at the

time made it difficult for insurers to determine accurate premiums. This

uncertainty, combined with the catastrophic nature of flooding, would

have required premiums that many consumers might not have been able

to afford. In 1968, Congress created NFIP to help reduce the escalating

costs of providing federal flood assistance to repair damaged homes and

8

We assessed the reliability of these data by comparing data elements to totals from other

sources. We also interviewed NAIC officials about the accuracy and limitations of the data

and their process for ensuring reliability. We determined that the data were sufficiently

reliable to describe trends in the private flood insurance market.

9

FEMA’s WYO program allows private insurers to sell and service policies and adjust

claims for NFIP.

Background

Page 5 GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

businesses.

10

NFIP was also intended to address the policy objectives of

identifying flood risk, offering reasonable insurance premiums to

encourage program participation, and promoting community-based

floodplain management.

11

Community participation in NFIP is voluntary. For a community’s

residents to purchase flood insurance through the program, the

community must participate in NFIP.

12

Participation requires communities

to meet certain requirements, including enforcing regulations for land use,

building standards, and new construction in special flood hazard areas

(SFHA).

13

FEMA uses community assistance visits and community

assistance contacts to oversee community enforcement of NFIP

requirements. Community assistance visits are on-site assessments of a

community’s floodplain management program and its knowledge and

understanding of NFIP’s floodplain management requirements.

In 1990, FEMA implemented a voluntary incentive program for

communities participating in NFIP called the Community Rating System

(CRS) to recognize and encourage community floodplain management

activities that exceed the minimum NFIP requirements. According to

FEMA, CRS’s goals are to reduce and avoid flood damage to insurable

property, strengthen and support the insurance aspects of NFIP, and

foster comprehensive floodplain management. Communities may apply to

join CRS if they are in full compliance with the minimum NFIP floodplain

management requirements. FEMA groups CRS communities into classes

based on their ratings. Communities can improve their ratings by earning

CRS credits for activities such as increasing public information about

flood risks, preserving open space, taking steps to mitigate flood damage,

and preparing residents for floods. Policyholders in these communities

10

Pub. L. No. 90-448, Tit. XIII, 82 Stat. 476, 572 (1968).

11

On June 1, 2023, 10 states and multiple local jurisdictions filed a lawsuit in the Eastern

District of Louisiana against FEMA alleging, among other claims, that Risk Rating 2.0 is

inconsistent with the objective of making flood insurance available when necessary at

reasonable rates and that the agency’s actions violated legal requirements of notice and

comment rulemaking. Louisiana, et. al. v. Mayorkas, Case No. 2:23-cv-01839 (E.D. La.

June 1, 2023). We do not address this lawsuit or any legal authorities discussed in the

lawsuit in this report.

12

As of May 2023, FEMA had identified 24,767 communities across the United States. Of

these, 22,621 (91 percent) participated in NFIP.

13

SFHAs are land areas that would be submerged by the floodwaters of the “base flood”—

a flood that has a 1 percent chance of being equaled or exceeded in any given year.

Community Participation,

WYO Program, and

Purchase Requirements

Page 6 GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

receive a discount on their flood insurance premiums ranging from 5 to 45

percent, depending on the community’s rating.

Consumers can purchase NFIP policies from a licensed property and

casualty agent. Most agents sell policies underwritten through FEMA’s

WYO program, which allows private insurers to sell and service policies

and adjust claims for NFIP. To become a WYO insurer, private insurers

enter into an arrangement with FEMA to issue flood policies in their own

name. The insurers must have experience in property and casualty

insurance lines, be in good standing with state insurance departments,

and be capable of selling and servicing the policies. WYO insurers do not

assume any risk, and they receive an expense allowance for their

services (currently about 30 percent of the premium a policyholder pays).

Agents can also contract directly with FEMA to sell NFIP policies under

the agency’s NFIP Direct program.

14

Consumers pay the same premium,

regardless of how they purchase their policy.

Generally, homeowners with federally backed mortgages in SFHAs have

been required by law to purchase flood insurance since 1973.

15

As part of

its role in administering NFIP, FEMA develops floodplain maps—

historically known as Flood Insurance Rate Maps (FIRM)—that provide

the basis for identifying which properties are required to purchase flood

insurance by delineating the boundaries of SFHAs.

16

Properties located in

these areas that have certain federally backed mortgages are subject to

the mandatory purchase requirement for flood insurance.

In October 2021, FEMA began implementing a new methodology for

calculating flood insurance premiums, known as Risk Rating 2.0.

Beginning on October 1, 2021, all new NFIP policyholders were required

to pay the full-risk premium determined using Risk Rating 2.0, and all

renewing policyholders were able to opt into Risk Rating 2.0 if it lowered

14

As of January 2020, approximately 88 percent of NFIP policies were sold by companies

participating in the WYO program, and 12 percent of policies were sold through the NFIP

Direct Servicing Agent.

15

42 U.S.C § 4012a. Federally backed mortgages are those made, insured, or guaranteed

by federally regulated lenders or federal agencies, or purchased by the government-

sponsored enterprises for housing—Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

16

FEMA floodplain maps also serve as the basis for local floodplain management

standards that communities must adopt and enforce as part of their NFIP participation.

Prior to Risk Rating 2.0, FEMA also used its floodplain maps to set premiums.

Risk Rating 2.0 and

Authority for Premium

Increases

Page 7 GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

their premium.

17

Beginning on April 1, 2022, all NFIP policyholders

became subject to the new methodology as their policies were renewed,

so that as of April 1, 2023, all NFIP policies were subject to Risk Rating

2.0.

18

Under the legacy methodology, some properties (also known as “pre-

FIRM” properties) paid discounted “subsidized” premiums if they were

built before floodplain maps for their area were published and flood risk in

those locations was properly understood. Other policies paid discounted

“grandfathered” premiums when a new flood map placed them into a

flood zone that would have increased their premiums; these properties’

premiums continued to be based on the previous, lower-risk flood zone.

Premium increases for renewing NFIP policies are generally limited by

statute.

19

For most policies, FEMA is prohibited from increasing premiums

by more than 18 percent per year.

20

FEMA is also required by law to

increase premiums by 25 percent per year for certain other policies until

they reach full risk, such as those covering pre-FIRM secondary

residences, businesses, and severe repetitive loss properties.

21

FEMA is

to increase premiums from 5 to 15 percent per year for certain other

policies, including those covering properties that were built before flood

maps were available for their area.

17

FEMA refers to its premiums that encompass all of the elements of the individual risk

transfer as full-risk premiums.

18

NFIP policies generally have a 1-year term. We refer to annual premium amounts that

reflect the policy term.

19

42 U.S.C. § 4015(e).

20

FEMA also is prohibited from increasing premiums for certain groups of policies with the

same flood risk classification by more than 15 percent per year on average. Such groups

include properties that were built before flood maps were available for their area and

properties that pay discounted premiums because they were newly mapped into an SFHA

on or after April 1, 2015, if the applicant gets flood insurance coverage within a year of the

mapping.

21

A severe repetitive loss property is an NFIP-insured structure that has incurred flood-

related damage for which (a) four or more separate claims have been paid that exceeded

$5,000 each and cumulatively exceeded $20,000, or (b) at least two separate claim

payments have been made under such coverage, with the cumulative amount of such

claims exceeding the fair market value of the insured structure. 42 U.S.C. § 4104c(h); 42

U.S.C. § 4014(h).

Page 8 GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

FEMA generally pays claims and funds its operations from premium

revenue from policyholders. In addition to paying for flood claims and

adjustment expenses, FEMA uses premium revenue to pay other costs,

including WYO expense allowances, interest on debt, operating

expenses, and mitigation grants.

FEMA offers coverage to homeowners, renters, and businesses for

buildings and their contents.

22

In addition to premiums for building and

contents coverage, NFIP policyholders pay separate assessments,

surcharges, and fees (see table 1).

Table 1: National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) Policyholder Assessments, Surcharges, and Fees

Charge

Authority

Purpose

Amount

FEMA authority

Reserve fund

assessment

Biggert-Waters Flood

Insurance Reform Act of

2012 (codified as

amended at 42 U.S.C. §

4017a)

Establish and maintain a

reserve fund to cover

future claim and debt

expenses, especially

those from catastrophic

disasters

18% of current premium

per policy starting on

April 1, 2020 (previously

15% since April 2016)

The Federal Emergency

Management Agency

(FEMA) has limited

authority to determine the

amount (statute specifies

a reserve fund target and

minimum annual

payments into the fund

until the target is

reached).

Homeowner

Flood Insurance

Affordability Act

surcharge

Homeowner Flood

Insurance Affordability

Act of 2014 (codified at

42 U.S.C. § 4015a)

Offset the cost of

discounted premiums

$25 for primary

residences; $250 for all

other properties

FEMA has no authority to

determine the amount or

eliminate the surcharge

before statutory

requirements for full-risk

premiums are generally

universally met—that is,

nearly all NFIP policies

must be at full-risk, with

some exceptions.

Federal Policy

Fee

Omnibus Budget

Reconciliation Act of

1990 (codified as

amended at 42 U.S.C. §

4014 (a)(1)(B)(iii))

Pay for administrative

expenses incurred in

carrying out flood

insurance and floodplain

mapping activities

$47 for all policies under

Risk Rating 2.0

(previously $50 and $25,

depending on policy type,

since October 2017)

FEMA has certain

authority to determine the

amount.

Source: GAO. | GAO-23-105977

22

NFIP’s maximum coverage limit for one-to-four-family residential policies is $250,000 for

buildings and $100,000 for contents. For nonresidential policies, the maximum coverage

limit is $500,000 per building and $500,000 for the building owner’s contents. NFIP

policies offer a variety of deductible options. Renters can purchase contents-only

coverage. FEMA also offers Increased Cost of Compliance coverage, which provides up

to $30,000 to help cover the cost of mitigation measures following a flood loss when a

property is declared to be substantially or repetitively damaged.

NFIP Funding Structure

and Flow of Funds

Page 9 GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

Note: In addition to premiums, which are based on risk, NFIP policyholders pay separate

assessments, surcharges, and fees.

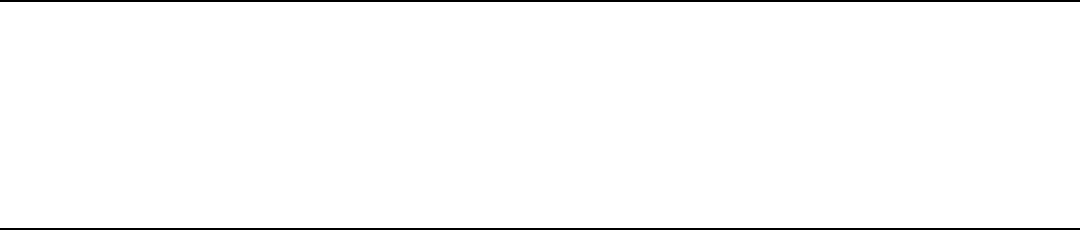

For example, a hypothetical single-family primary residence had been

paying an annual premium of $1,017 prior to Risk Rating 2.0. Under Risk

Rating 2.0, FEMA determined that this hypothetical policyholder should

be paying $2,200 to reflect the full risk of loss of the insured property.

Because this policy is subject to an 18 percent statutory cap on annual

premium increases, in the first year FEMA can only raise the premium by

18 percent, from $1,017 to $1,200. Therefore, in the first year of Risk

Rating 2.0, the policyholder receives a $1,000 discount relative to the full-

risk premium of $2,200. The policyholder then pays $288 in additional

assessments, surcharges, and fees, bringing the total payment to $1,488.

The premium will increase each year, subject to the statutory caps, until

the full-risk premium is reached. Figure 1 illustrates the costs for this

hypothetical policyholder in the first year under Risk Rating 2.0.

Page 10 GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

Figure 1: Policyholder Costs for a Hypothetical National Flood Insurance Program Policy

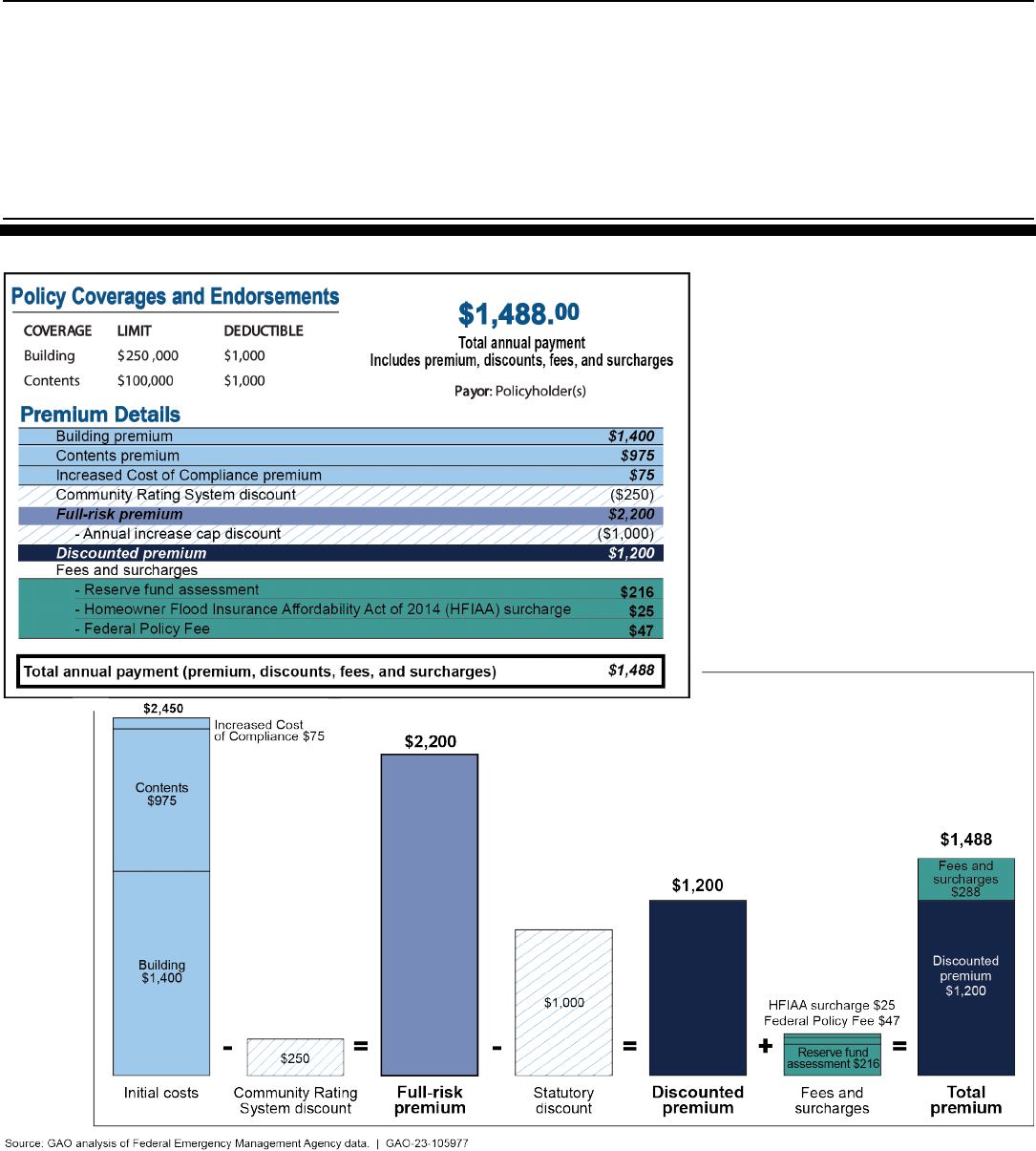

FEMA also has reinsurance agreements and borrowing authority from

Treasury to fulfill its obligations. Collections are deposited into an

Page 11 GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

insurance fund, and some are transferred to a reserve fund (see fig. 2).

23

In most years, NFIP premium revenue is sufficient to pay claims and

generate a cash surplus. In years when losses exceed premium revenue,

FEMA uses any amounts in these funds to pay claims, first from the

insurance fund and then, if necessary, from the reserve fund. When

individual or accumulated losses in a year exceed a certain threshold,

FEMA can receive payouts from its reinsurance agreements. When

revenue, reinsurance, and any accumulated surplus are insufficient,

FEMA has authority to borrow from the Treasury.

24

Figure 2: National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) Flow of Funds

Note: All policyholder payments are deposited into the National Flood Insurance Fund, but the

reserve fund assessment and Homeowner Flood Insurance Affordability Act (HFIAA) surcharge are

transferred into the National Flood Insurance Reserve Fund.

23

The National Flood Insurance Fund was established in the U.S. Treasury by the

National Flood Insurance Act of 1968. The National Flood Insurance Reserve Fund was

established by the Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act of 2012 to help meet future

NFIP obligations and principal and interest payments on any outstanding Treasury loans

(42 U.S.C. § 4017a). Specifically, FEMA is required to establish a reserve fund with a

balance equal to 1 percent of the sum of the total potential loss exposure of all

outstanding flood insurance policies in force in the prior fiscal year. FEMA’s total exposure

in fiscal year 2022 was $1.28 trillion, which equates to a target reserve fund balance of

$12.8 billion for fiscal year 2022. FEMA is required to contribute at least 7.5 percent of its

target balance each year until it achieves the target reserve fund balance. This equates to

a reserve fund contribution of $960 million for fiscal year 2022.

24

42 U.S.C. § 4016. Congress authorized FEMA to borrow from the Treasury when

needed, up to a preset statutory limit. Originally, Congress authorized a borrowing limit of

$1 billion and increased it significantly in 2005 and 2013. The limit currently stands at

$30.425 billion.

Page 12 GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

In developing Risk Rating 2.0, FEMA applied actuarial principles to better

align premiums with flood risk, representing a substantial improvement

from its legacy ratemaking methodology. The methodology and process

FEMA used to develop full-risk premiums in Risk Rating 2.0 generally

reflect statutory premium requirements and relevant actuarial principles

and standards.

25

According to FEMA, Risk Rating 2.0 was the first change in its ratemaking

methodology since the 1970s. The legacy methodology had become out

of date for several key reasons, including that it largely based premiums

on a property’s height relative to the base flood elevation and broadly

defined flood zone and charged the same premium nationwide based on

these characteristics.

26

The legacy rating methodology also did not

capture many potential flood sources or reflect flood risk from

catastrophic events. We previously identified a number of challenges with

this ratemaking process.

27

25

42 U.S.C. § 4014(a). Casualty Actuarial Society, Statement of Principles Regarding

Property and Casualty Ratemaking (Arlington, Va.: May 7, 2021). The Actuarial Standards

Board’s relevant Actuarial Standards of Practice include 12 (Risk Classification for All

Practice Areas); 23 (Data Quality); 25 (Credibility Procedures); 29 (Expense Provisions in

Property/Casualty Insurance Ratemaking); 30 (Treatment of Profit and Contingency

Provisions and the Cost of Capital in Property/Casualty Insurance Ratemaking); 38

(Catastrophe Modeling); 39 (Treatment of Catastrophe Losses in Property/Casualty

Insurance Ratemaking); 53 (Estimating Future Costs for Prospective Property/Casualty

Risk Transfer and Risk Retention); and 56 (Modeling).

26

Under the legacy methodology, SFHAs included two categories of flood zones: A (high-

risk noncoastal) and V (high-risk coastal). Non-SFHAs generally included three

categories: B, C, and X (low to moderate risk).

27

See GAO, National Flood Insurance Program: Continued Progress Needed to Fully

Address Prior GAO Recommendations on Rate-Setting Methods, GAO-16-59

(Washington, D.C.: Mar. 17, 2016) and Flood Insurance: FEMA’s Rate-Setting Process

Warrants Attention, GAO-09-12 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 31, 2008).

Risk Rating 2.0

Significantly Improves

Ratemaking, but

Certain Aspects of

NFIP Limit Actuarial

Soundness

With Risk Rating 2.0,

FEMA Improved

Ratemaking by Applying

Actuarial Principles

Page 13 GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

Under Risk Rating 2.0, FEMA better aligns premiums with flood risk and

takes advantage of new technology and advances in the insurance

industry’s understanding of flood risk. For instance, Risk Rating 2.0 does

the following:

• Ties premiums to individual property flood risk rather than to

broadly defined flood zones. Premiums under the legacy

methodology relied heavily on a structure’s flood zone as depicted on

FEMA’s floodplain maps.

28

Structures within each flood zone

generally were rated similarly, meaning that while properties may

have had different premiums because of other variables (e.g.,

occupancy type and elevation), the premium did not vary based on

the property’s particular geographic location within the zone. Risk

Rating 2.0 calculates premiums based on the characteristics of each

individual insured structure and no longer uses the flood zone.

• Integrates input from commercial catastrophe models.

Catastrophe models are computerized processes that simulate

potential losses due to catastrophic events, such as floods.

29

Their

use has become standard practice in the insurance industry since

they were first developed in the 1980s. The models have evolved

significantly as technology has advanced and exposure data have

improved. Under Risk Rating 2.0, FEMA uses catastrophe models to

estimate the annual losses from potential flood events.

• Accounts for more sources of flooding. The previous methodology

accounted only for coastal and riverine flooding, but Risk Rating 2.0

also includes pluvial (rainfall), Great Lakes, coastal erosion, and

tsunami flooding.

• Accounts for the replacement cost value of the property. NFIP

residential coverage is generally limited to $250,000. Although the

legacy methodology did not adjust premiums based on the value of

the insured property, insured homes with values above the $250,000

limit still affected NFIP’s risk exposure. For example, $250,000 in

coverage was priced the same for a $250,000 home as for a $5

million home. However, this approach was inequitable because the

same flooding event is likely to cause more damage to a higher-value

structure. For example, $250,000 in damage to a $250,000 home—a

28

FEMA floodplain maps are the official maps of communities on which FEMA has

delineated the SFHA and base flood elevations applicable to the community.

29

Actuarial standards of practice define a catastrophe model as a model of low-frequency

events with high-severity or widespread potential effects. Catastrophe models may be

used to explain a system, to study effects of different components, or to derive estimates.

Page 14 GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

total destruction of home value—would occur only with an infrequent

severe flood event. In contrast, $250,000 of damage to a $5 million

home—a destruction of just 5 percent of home value—could occur

with far less severe and more frequent flood events. As a result, the

$5 million home has a much higher probability of incurring $250,000 in

damage than does a $250,000 home, and should have a higher

premium. By not accounting for this difference in probabilities, the

legacy rating methodology tended to undercharge homes that are

more expensive and overcharge homes that are more modest. By

incorporating replacement cost value into its ratemaking, Risk Rating

2.0 more accurately accounts for differences in flood risk from

properties of different values.

In its Risk Rating 2.0 ratemaking process, FEMA incorporates the

damage or loss estimates of multiple catastrophe models, which include

commercial models as well as FEMA models that use data from other

government agencies, including the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

These models do not produce suggested premium rates, but FEMA uses

the output of these models in its ratemaking process. According to FEMA,

the agency makes use of multiple catastrophe models because, although

each model has its own strengths, no single model adequately covers all

circumstances. For example, FEMA uses data from the U.S. Army Corps

of Engineers to model damage and losses in areas behind levees, and it

uses data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and

other agencies to model coastal flooding. Catastrophe models, including

those used by FEMA, are generally based on simulations and thus

involve some amount of uncertainty.

NFIP is statutorily required to develop premiums that are actuarially

sound.

30

According to actuarial principles, an actuarially sound premium

is an estimate of the expected value of future costs of the individual risk

transfer.

31

These expected costs include insurance claims, claims-related

30

42 U.S.C. § 4014(a).

31

Casualty Actuarial Society, Statement of Principles. Further, the Actuarial Standards

Board sets standards for appropriate actuarial practice in the United States through the

development and promulgation of Actuarial Standards of Practice, which describe the

procedures an actuary should follow when performing actuarial services and identify what

the actuary should disclose when communicating the results of those services. According

to Actuarial Standard of Practice 1, “actuarial soundness” has different meanings in

different contexts and might be dictated or imposed by an outside entity. In rendering

actuarial services, if the actuary identifies a process or result as “actuarially sound,” the

actuary should define the meaning of “actuarially sound” in that context.

Page 15 GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

expenses, commissions, operational expenses, reinsurance costs, and a

provision for retained risk.

32

Actuarial principles also state that an

actuarially sound premium should be reasonable and should not be

excessive, inadequate, or unfairly discriminatory. In developing Risk

Rating 2.0, FEMA followed the statutory definition of actuarial rates and

followed recognized actuarial principles and actuarial standards of

practice.

33

FEMA refers to its premiums that encompass all of the

elements of the individual risk transfer as full-risk premiums.

The process of ratemaking under Risk Rating 2.0 included three core

components: creating market baskets representative of single-family

homes, estimating NFIP’s aggregate target premium, and allocating

individual premiums to policyholders. Creating market baskets involved

grouping U.S. single-family homes with several of the same risk factors

using geographic information system data and commercially available

data.

34

FEMA incorporated the market baskets into catastrophe models

from several vendors and modeled NFIP’s flood risk using policy data as

of May 31, 2018. According to FEMA officials, they updated their

assumptions using data as of May 31, 2020.

FEMA then developed NFIP’s aggregate target premium—the total

premium for the entire program—using the average annual losses

generated from the catastrophe models, as well as provisions for WYO

expense allowances, loss adjustment expenses, and the net cost of

reinsurance and retained risk.

FEMA then used the aggregate target premium to determine individual

policyholder premiums based on the risk factors of their insured

properties and the potential flood sources. FEMA used rating variables,

32

Reinsurance is insurance for insurers. The net cost of reinsurance includes the excess

of reinsurance premiums paid to the reinsurer over recoveries for claims from the

reinsurer. Retained risk is the exposure that an insurer chooses to cover itself rather than

transferring it to a third party, such as a reinsurer, and includes the risk of random

variation from expected costs plus the risk of systematic underestimation of expected

costs. In private-sector contexts, a provision for risk is also referred to as a cost of capital.

33

The statutory definition of an actuarial rate is one that covers all costs, as prescribed by

principles and standards of practice in ratemaking adopted by the American Academy of

Actuaries and the Casualty Actuarial Society, including an estimate of the expected value

of future costs, all costs associated with the transfer of risk, and the costs associated with

an individual risk transfer with respect to risk classes, as defined by FEMA. 42 U.S.C. §

4014 (a)(1)(B)(iv).

34

Data sources included the U.S. Geological Survey, the National Oceanic and

Atmospheric Administration, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Page 16 GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

which are characteristics that have been shown through analysis to

correlate with the likelihood of losses. When developing rating factors,

FEMA compared the annual expected losses derived from the

catastrophe models to NFIP’s historical losses from January 1, 1992, to

June 30, 2018, and adjusted accordingly. Specifically, FEMA compared a

range of modeled losses for each market basket of properties to the

historical losses experienced by actual policies within that market basket

to verify whether the historical losses fell into the model’s estimated

range.

FEMA performed a rating factor analysis by peril separately for single-

family homes not protected by a levee, single-family homes protected by

a levee, and non-single-family homes.

35

FEMA’s analyses identified a set

of rating factors that reflect several characteristics:

• location (including distance to flooding sources and elevation relative

to flooding sources);

• structural characteristics (including occupancy type, foundation type,

first floor height, number of floors, construction type, existence of flood

openings, and location of machinery and equipment); and

• replacement cost value, coverage, and deductible amounts.

All of these rating factors combined allow FEMA to group policyholders

with similar risks together to help determine the full-risk premium. FEMA

officials told us they plan to review and update premiums to continue

using the best available data, science, and models. They also plan to

account for changes in other factors, such as flood risk and their

understanding of it, as well as changes in inflation, expenses, fees, and

policyholder population.

In addition to premiums, NFIP policyholders pay separate charges that

are determined outside of the actuarial ratemaking process. These

additional charges are not proportional to the individual risk of the insured

property and result in some policyholders being charged more than the

actuarial cost of the risk transfer.

35

Risk Rating 2.0 accounts for the level of risk reduction that levees provide to the

buildings located behind them. Levees reduce flood risk but do not eliminate it. According

to FEMA, limitations of levees include their capacity to reduce flooding in leveed areas

(from overtopping) and their ability to perform adequately during flood events, and this

information is fundamental in assessing the risk.

Some Additional

Policyholder Charges Limit

Actuarial Soundness

Page 17 GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

• Reserve fund assessment. FEMA is statutorily required to establish

and maintain a reserve fund to provide additional funds to cover future

claims and debt expenses, especially those from catastrophic

disasters. Specifically, FEMA must move toward a target balance of 1

percent of insurance-in-force by making minimum annual

contributions of 7.5 percent of the target balance until the fund

reaches the target.

36

FEMA does so by implementing a reserve fund

assessment, which FEMA has set at 18 percent of the premium since

2020.

37

FEMA applies the reserve fund assessment to the discounted

premium rather than the full-risk premium. As a result, the

assessment is not proportional to the actual risk of the property.

38

FEMA officials told us that they view the reserve fund assessment as

a capitalization charge that is separate from the full-risk premium.

However, FEMA also includes in its full-risk premium a risk load for

the risk of future catastrophic losses, in accordance with actuarial

principles. As a result, the statutorily required reserve fund

assessment results in policyholders paying a charge for catastrophic

losses in two places, and being at risk of overpaying the cost of risk

transfer, especially policyholders paying full-risk premiums.

39

• Homeowner Flood Insurance Affordability Act (HFIAA)

surcharge. The HFIAA surcharge, which was statutorily established

and offsets the cost of discounted premiums, is set at $25 for primary

residences and $250 for other properties. Because the HFIAA

surcharge is a flat amount, it is not tied to the risk of the individual

36

42 U.S.C. § 4017a(b)(1),(d)(1).

37

FEMA initially set the reserve fund assessment at 5 percent but increased it to 15

percent in April 2016 and 18 percent in April 2020.

38

For example, a policyholder who pays a full-risk premium would pay a higher reserve

fund assessment than a policyholder with the same risk who pays a discounted premium.

39

FEMA is required to develop rates based on actuarial principles and in consideration of

risk to include operating and administrative expenses. 42 U.S.C. § 4014. This includes a

risk load for catastrophic losses, according to FEMA officials. Further, FEMA officials

stated that Risk Rating 2.0 includes this catastrophic load in the premium and that this

premium must be deposited into the National Flood Insurance Fund. Additionally, FEMA is

generally required by statute to increase premiums to fund the reserve fund to meet the

target or reserve ratio for the year. 42 U.S.C. § 4017a. FEMA officials stated that the

reserve fund assessment should not be viewed as an actuarial charge, but as a

congressional mandate. Additionally, FEMA officials stated that the reserve fund

assessment is subject to the aggregate annual premium increase cap of 18 percent a

year. According to FEMA, due to this constraint, policyholders who are paying their full-

risk rate will be charged the full reserve fund assessment, while those policyholders

receiving a premium increase discount will not pay the full reserve fund assessment.

Additionally, all premium increases to build up the reserve fund must be deposited into the

reserve fund. 42 U.S.C. § 4017a.

Page 18 GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

property, and while the $25 surcharge for primary residences is

relatively small, the $250 surcharge for other properties is not. In

addition, while the HFIAA surcharge offsets the cost of discounted

premiums, it is charged to all policyholders, including those already

paying the full-risk premium, so that these policyholders are partially

subsidizing policyholders paying discounted premiums. The amount of

the HFIAA surcharge is set in statute, so FEMA lacks the authority to

eliminate or reduce it until statutory requirements for full-risk

premiums are generally universally met—that is, nearly all NFIP

policies must be at full-risk, with some exceptions.

Because the full-risk premium covers the full cost of the risk transfer,

including a risk load, policyholders paying the full-risk premium plus the

reserve fund assessment and the additional HFIAA surcharge are paying

more than the actuarially determined cost of insurance. Moreover, the

size and duration of the reserve fund assessment will vary with claims

experience. For example, if the reserve fund is used to help pay claims in

a catastrophic loss year, the reserve fund assessment might need to be

increased, extended, or reinstated to reach the target balance. This would

result in current or future policyholders paying for past losses, in violation

of actuarial principles.

To the extent that the reserve fund assessment and HFIAA surcharge are

not proportional to the individual risk of the insured property or result in

policyholders paying more than an actuarially justified cost of the risk

transfer, the total costs a policyholder pays will not be actuarially sound.

Specifically, FEMA cannot ensure that the amounts charged align with the

flood risk of specific properties, which limits the ability of these charges to

accurately signal flood risk and results in some policyholders overpaying

and others potentially underpaying. Were Congress to authorize and

require FEMA to incorporate the reserve fund assessment, to the extent

necessary based on actuarial principles, into the risk charge within the

full-risk premium, it would enhance the actuarial soundness of the total

costs policyholders pay. Further, were Congress to repeal the HFIAA

surcharge and authorize and require FEMA to replace forgone revenue

with actuarially determined premium adjustments, it would enhance the

actuarial soundness of the total costs policyholders pay.

Premium discounts provided under the CRS program are not actuarially

justified and are paid for, in large part, through a cross-subsidization by

policyholders not receiving the discount. As previously discussed, FEMA

uses premium discounts ranging from 5 to 45 percent to promote CRS

program goals: to reduce and avoid flood damage to insurable property,

CRS Discounts Are Not

Actuarially Justified

Page 19 GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

to strengthen and support the insurance aspects of NFIP, and to foster

comprehensive floodplain management.

40

As a community engages in

additional eligible activities, its residents become eligible for larger

premium discounts.

FEMA officials told us they set full-risk premiums so that after applying

the CRS discounts, the total premium revenue within each state

represents the full aggregate risk of all policies in that state. This

approach results in a cross-subsidy because policyholders outside of

CRS communities are paying higher premiums than are actuarially

justified to subsidize the discounts that policyholders in participating CRS

communities receive.

Further, it is likely that policyholders receiving the CRS discount are

paying lower premiums that do not fully reflect their flood risk. The

amounts of CRS discounts—both to individual properties and program-

wide—are not closely linked to potential loss reduction of currently

insured properties. While the activities that FEMA promotes through CRS

are important, few of them directly mitigate flood risk in the policy

period.

41

FEMA officials told us that CRS helps improve future resilience

to flood risk but does little to reduce the estimated flood losses of the

properties NFIP currently insures.

42

For example, four eligible activities

reduce potential flood damage: floodplain management planning,

acquisition and relocation, flood protection, and drainage system

maintenance.

43

However, CRS provides discounts for 15 other activities

related to public information, mapping and regulations, and warning and

response that do not reduce the potential for flood damage to currently

40

As of May 2023, 22,621 communities participated in NFIP. As of April 2023, 1,504 NFIP

communities received a CRS discount, and 454 received a discount of at least 20 percent.

41

Until October 2021, discounts were available only to properties in SFHAs, but under

Risk Rating 2.0, FEMA provides discounts to all policies in a participating community.

42

Broadly speaking, resilience is the ability to prepare and plan for, absorb, recover from,

and more successfully adapt to actual or potential adverse events.

43

FEMA defines floodplain management planning as the adoption of flood hazard

mitigation or natural functions plans using the CRS planning process, or conducting

repetitive loss area analyses. Acquisition and relocation refer to acquiring insurable

buildings and relocating them out of the floodplain and leaving the property as open

space. Flood protection of the insured building includes activities such as floodproofing,

elevation, or minor structural projects. Drainage system maintenance includes annual

inspections of channels and retention basins and maintenance of the drainage system’s

flood-carrying and storage capacity

Page 20 GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

insured properties.

44

While we recognize the value of such activities, it is

not actuarially justifiable to incentivize them through premium discounts or

through overcharging policyholders outside of CRS communities. FEMA

has not evaluated the actuarial benefits of these other activities in terms

of loss mitigation or other means of incentivizing them.

In addition, FEMA officials stated that some of the rating variables used in

Risk Rating 2.0 already account for the reduced flood risk that results

from certain CRS activities in calculating full-risk premiums. For example,

one rating variable is a property’s elevation height in relation to flood

sources. Elevating properties is one activity a community could undertake

to receive a CRS discount. As a result, some properties could receive

lower premiums because they are elevated and also receive a CRS

discount for being located in a community that is working to elevate

properties. At the same time, nonelevated properties in the community

would still receive the CRS discount without having received any risk-

reduction benefit from the community’s activities.

Actuarial principles suggest that the amount of premium discount should

align with the amount of loss reduction for each individual property.

Further, while statute requires FEMA to apply CRS discounts, it does not

prescribe the amount of the discounts or the specific community activities

FEMA should use to determine them.

45

Rather, it says that FEMA should

provide CRS discounts based on the estimated reduction in flood risk

from the measures adopted by the community.

If FEMA does not adjust CRS ratings so that only community activities

that can be actuarially justified to reduce flood risk contribute toward a

community’s rating and does not incorporate discounts into the full-risk

premium based on the actuarial evaluation of risk reduction, then

premiums will not be actuarially sound, and policyholders will continue

over- or underpaying premiums. Further, by evaluating other means of

incentivizing desirable community-wide activities that cannot be

44

Public information activity categories include elevation certificates, map information

service, outreach projects, hazard disclosure, flood protection information, flood protection

assistance, and flood insurance promotion. Mapping and regulations activity categories

include floodplain mapping, open space preservation, higher regulatory standards, flood

data maintenance, and stormwater management. Warning and response activity

categories include flood warning and response, levees, and dams.

45

42 U.S.C. § 4022(b).

Page 21 GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

actuarially justified, FEMA could help ensure such activities continue if

they are no longer incentivized through CRS discounts.

Implementing Risk Rating 2.0 is helping FEMA to address NFIP’s

historical premium inadequacy and overall actuarial soundness, but

Congress and the public do not have certain information on the new

methodology and NFIP’s long-term fiscal outlook.

FEMA has communicated Risk Rating 2.0’s actuarial soundness and

NFIP’s fiscal outlook to Congress through three primary means:

• Legislative reform proposals. In May 2022, the Department of

Homeland Security submitted to Congress 17 legislative proposals

that included establishing a “Sound Financial Framework.”

46

According to FEMA, the framework would call for NFIP to pay all

claims for a flood event that has a 5 percent chance of being

exceeded in any given year—about $10.5 billion, similar to claims

from Hurricane Harvey in 2017. Congressional action on an

emergency supplemental appropriation would be needed only if

claims exceeded this amount. FEMA said this framework would

require the implementation of several reforms.

47

FEMA estimated the

framework would result in a 75 percent likelihood that NFIP could

manage flood events up to the established ceiling and have a positive

balance in its available funds at the end of a 10-year period.

• Budget request. In its 2024 budget request, FEMA estimated the

budgetary effects of its proposed reforms for establishing the

framework.

48

FEMA also requested an equalization payment to cover

what it estimated to be the cost of premium discounts in fiscal year

2024.

46

Department of Homeland Security, Legislative Reform Package (Washington, D.C.: May

11, 2022).

47

To achieve the Sound Financial Framework, FEMA proposed (1) canceling the existing

debt, (2) eliminating interest on future debt, (3) decreasing NFIP’s borrowing authority

from $30.425 billion to two-thirds of total expected premiums in force in the following fiscal

year, (4) directing annual equalization payments to cover premium shortfalls from

discounted premiums, (5) allowing the ability to transfer funds between the insurance and

reserve funds, (6) eliminating the Reserve Fund Ratio, and (7) eliminating the HFIAA

surcharge.

48

Office of Management and Budget, Budget of the U.S. Government, Fiscal Year 2024—

Department of Homeland Security (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 9, 2023).

FEMA Has Not Fully

Reported on Risk Rating

2.0’s Actuarial Soundness

and Its Effect on NFIP’s

Fiscal Exposure

Page 22 GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

• Debt report to Congress. In August 2022, FEMA submitted to

Congress a report on NFIP’s debt as of March 2022.

49

The report

communicated the uncertainty of flood losses, NFIP’s estimated

annual losses for a 10-year period, and projections of NFIP’s debt and

financial position over this period.

In addition to these reports, FEMA posted on its website a report from its

actuarial contractor that describes the actuarial modeling and data

sources used in developing Risk Rating 2.0 premium rates.

These communications provide important information on NFIP, but

Congress and the public lack some information because these

communications are fragmented and incomplete. For example, FEMA’s

Sound Financial Framework communicates NFIP’s estimated capacity if it

were to receive annual equalization payments for the cost of premium

discounts and if its other requested reforms were implemented. However,

FEMA did not estimate NFIP’s current capacity (absent these reforms) or

estimate its future capacity for either scenario. The framework also does

not include a plan to regularly update these estimates. Further, FEMA has

designed full-risk premiums under Risk Rating 2.0 based on an estimated

average annual loss target but has not incorporated this estimate into

these communications. Moreover, while FEMA estimated premium

revenue and shortfalls for a 10-year period when preparing its budget

request, the actual budget request only included the estimates for 2024.

In addition, the 10-year projections in FEMA’s budget request and debt

report included a single baseline scenario rather than a range of

scenarios that would illustrate the uncertainty of NFIP’s future financial

condition.

One of FEMA’s strategic objectives is empowering risk-informed decision-

making, and FEMA’s strategic plan states that the availability of, access

to, and understanding of future conditions data and modeling within

FEMA must be expanded.

50

In this regard, a comprehensive annual

actuarial report could help better inform Congress and the public about

49

Department of Homeland Security, National Flood Insurance Program Semi-Annual

Debt Repayment Report, March 31, 2022 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 30, 2022).

50

Federal Emergency Management Agency, 2022–2026 FEMA Strategic Plan: Building

the FEMA Our Nation Needs and Deserves (Washington, D.C.: 2021).

Page 23 GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

Risk Rating 2.0’s actuarial soundness and NFIP’s fiscal outlook.

51

Ensuring that such a report is informed by relevant actuarial standards

would enhance its usefulness and credibility.

52

Elements of a comprehensive annual actuarial report could include

communicating the accuracy and adequacy of NFIP’s premiums in

managing the program’s fiscal exposure. The report could also

communicate the target loss level that full-risk premiums are designed to

cover, the uncertainty associated with the full-risk premium, and the

likelihood that the estimated premium revenue will cover the target loss

for the policy year. Further, the report could evaluate and communicate

estimated premium revenue and shortfall, the likelihood of additional

Treasury borrowing, and NFIP’s short- and long-term fiscal outlook under

a variety of scenarios for future claims experience and policy renewals,

lapses, and new policies. Without a comprehensive annual actuarial

report on Risk Rating 2.0’s soundness and NFIP’s fiscal outlook, available

information for overseeing the program will continue to be fragmented

and incomplete.

As noted earlier, a key goal of Risk Rating 2.0 is to more closely align

premiums with individual property flood risk. Because legacy premiums

on many policies do not fully reflect the underlying flood risk, aligning

51

Examples of comprehensive annual reports for other programs that involve actuarial

assessments of risk include the annual trustees’ reports for Social Security and Medicare

and the annual projections report produced by the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation.

52

For more information, see, for example, Actuarial Standards of Practice 41 (Actuarial

Communications), 46 (Risk Evaluation in Enterprise Risk Management), 47 (Risk

Treatment in Enterprise Risk Management), and 56 (Modeling).

Risk Rating 2.0 Is

Aligning Premiums

with Risks, but Some

Policyholders Face

Increasing

Affordability Concerns

Premiums Are Increasing

for Many Policies but Will

Better Reflect Flood Risk

Page 24 GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

premiums with risks will require premium increases on most policies.

53

As

of December 2022, NFIP policyholders paid a median annual premium of

$689.

54

However, the median annual full-risk premium was $1,288.

55

As a

result, the median premium will need to increase by almost 90 percent to

reach full risk.

56

However, different policies will require different premium changes to align

them with actual risk and reach full-risk premiums. For example, 35

percent of policies will require an increase of less than 100 percent, while

about 9 percent will require an increase of 300 percent or more (see fig.

3). Overall, about 66 percent of policies still required premium increases

as of December 2022. In September 2021, under the legacy

methodology, FEMA considered about 22 percent of its policies to be

paying premiums that were less than full risk.

57

In contrast, the fact that

66 percent of policies are paying less than full-risk premiums under Risk

53

As discussed previously, NFIP policyholders pay premiums, which are based on risk, as

well as separate assessments, surcharges, and fees. In this section, we analyzed the

entire amount a policyholder pays, including building premium, contents premium,

Increased Cost of Compliance premium, severe repetitive loss premium, reserve fund

assessment, HFIAA surcharge, Federal Policy Fee, and probation surcharge. CRS

discounts, when applicable, are also reflected. For simplicity and clarity, in this section we

refer to the total policyholder payments as “premiums.”

54

For condominiums, NFIP offers a Residential Condominium Building Association Policy,

which covers all units within a condominium. As a result, it is necessary to adjust for the

number of condominium units to determine the number of policies. We account for the

number of condominium units when reporting the aggregate number of NFIP policies, but

otherwise we treat these condominium policies as single policies.

55

FEMA determined full-risk premiums for policies subject to Risk Rating 2.0, which

includes new policies beginning October 1, 2021, and renewed policies beginning April 1,

2022. We analyzed NFIP data for policies in effect on December 31, 2022, which included

full-risk premiums that were valid as of that date for 89 percent of NFIP policies. Our

analysis excludes the remaining policies, which were due for renewal from January 1,

2023, to March 31, 2023, because FEMA had not yet determined their full-risk premiums.

Full-risk premiums are FEMA’s best estimates of the premium that would need to be

charged to cover the estimated cost of the risk transfer and associated expenses for the

year FEMA determined them. As noted earlier, FEMA officials told us they will modify

premiums as input factors change (such as housing values and flood risk) and as they

continue to improve their understanding of flood risk.

56

FEMA’s estimates of full-risk rates reflect current WYO expense allowances (about 30

percent of the premium a policyholder pays). As premiums increase with implementation

of Risk Rating 2.0, the amount of expense allowance per policy will increase. Any changes

to the compensation structure would affect the calculation of full-risk rates.

57

Under the legacy methodology, subsidized and grandfathered premiums were

considered less than full risk.

Page 25 GAO-23-105977 Flood Insurance

Rating 2.0 indicates that the legacy system significantly underestimated

flood risk and that Risk Rating 2.0 is correcting this underpricing.

Figure 3: Estimated Future Premium Changes under Risk Rating 2.0, as of

December 2022

Note: This analysis includes the 89 percent of policies subject to Risk Rating 2.0 and in effect on

December 31, 2022. The remaining 11 percent of policies were due for renewal from January 1,