Office Of ReseaRch and educatiOn accOuntability

student attendance in tennessee

MaRch 2021

JasOn e. MuMpOweR

Comptroller of the Treasury

dana bRiMM

Legislative Research Analyst

Table of contents

Disclaimer

Introduction

Methodology

Attendance according to Tennessee law and rule

Compulsory attendance

Attendance supervisors

Support sta for attendance supervisors

Local attendance policies

Excused versus unexcused absences

Parent notes

Conversion absences

Review of attendance data

Data misreporting

Chronic absenteeism as a national focus

Measuring chronic absenteeism by student group

Chronic absenteeism by student group

Economically disadvantaged students

Students with disabilities

English learners

Racial groups

Grade levels

Laws to combat absenteeism in upper grades

Chronic absenteeism by district

Chronic absenteeism by school

Chronically Out of School Indicator

Progressive truancy intervention plan

Tier 1 | Must be implemented once a student accrues ve unexcused absences

Tier 2 | Implemented if student violates the attendance contract signed in Tier 1

Tier 3 | Implemented if student continues to accrue unexcused absences after Tier 2

Legal action after the progressive truancy intervention plan

Measures taken by juvenile court judges in truancy cases

Charges against parents

Skipping tiers due to lack of parent cooperation

Restarting PTIP tiers at the beginning of each year

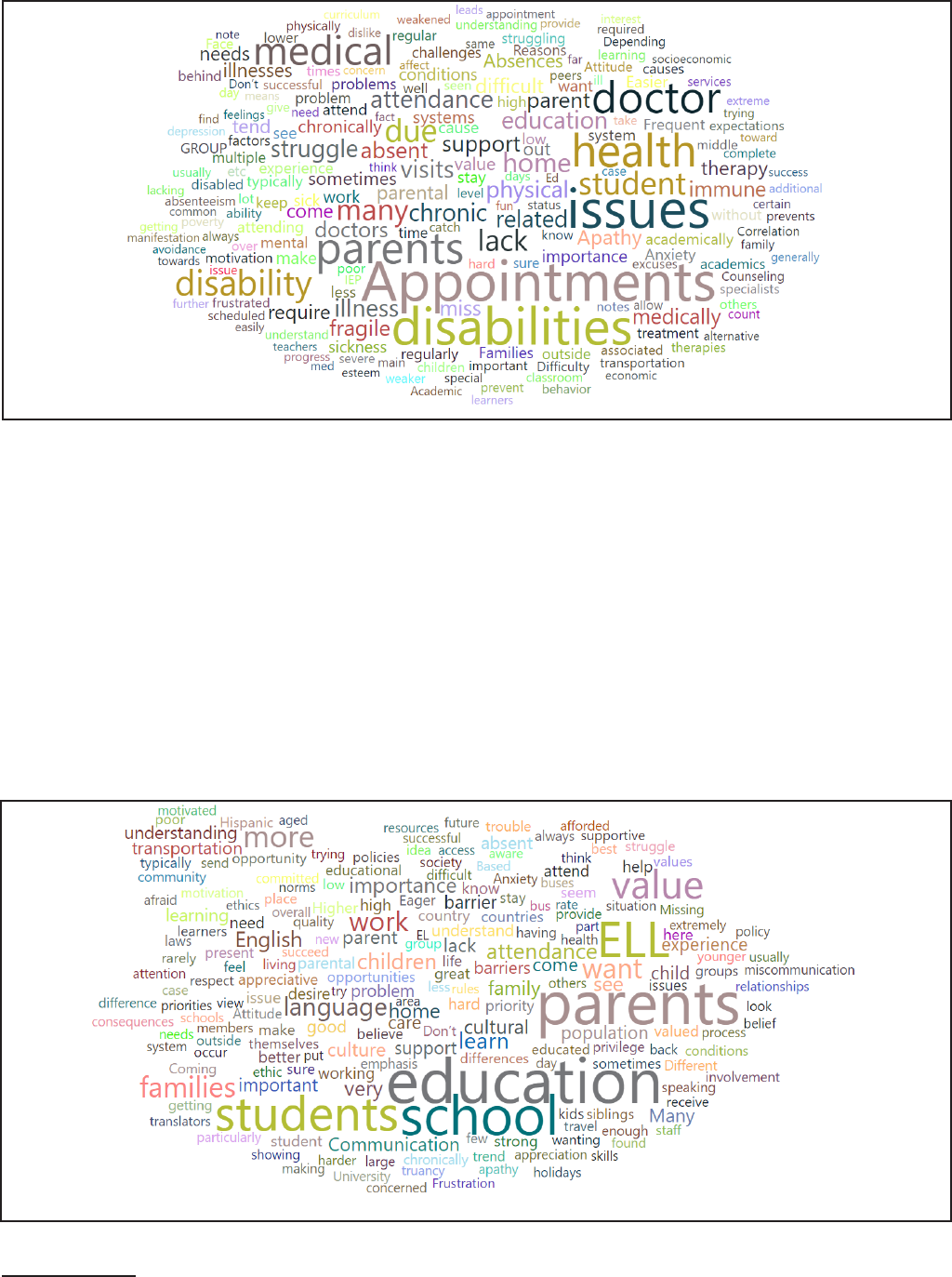

Top factors among chronically absent and/or truant students

Prolonged or chronic physical illnesses

Mental health

Alternative attendance plans

Parent issues

Students 18 and over

Student attitude

Tools for addressing student attendance

Coordinated School Health

School nurses

Incentives and competitions

5

5

6

6

6

7

8

9

9

11

12

15

15

17

18

20

20

22

23

24

25

28

30

32

33

34

35

37

38

39

40

40

44

44

45

47

48

48

50

51

51

52

53

54

54

Community school initiatives

Communities in Schools (CIS)

Other forms of student outreach

Discipline

Change in use of out-of-school suspension since chronic absenteeism measured

Student attendance and COVID-19

Conclusions

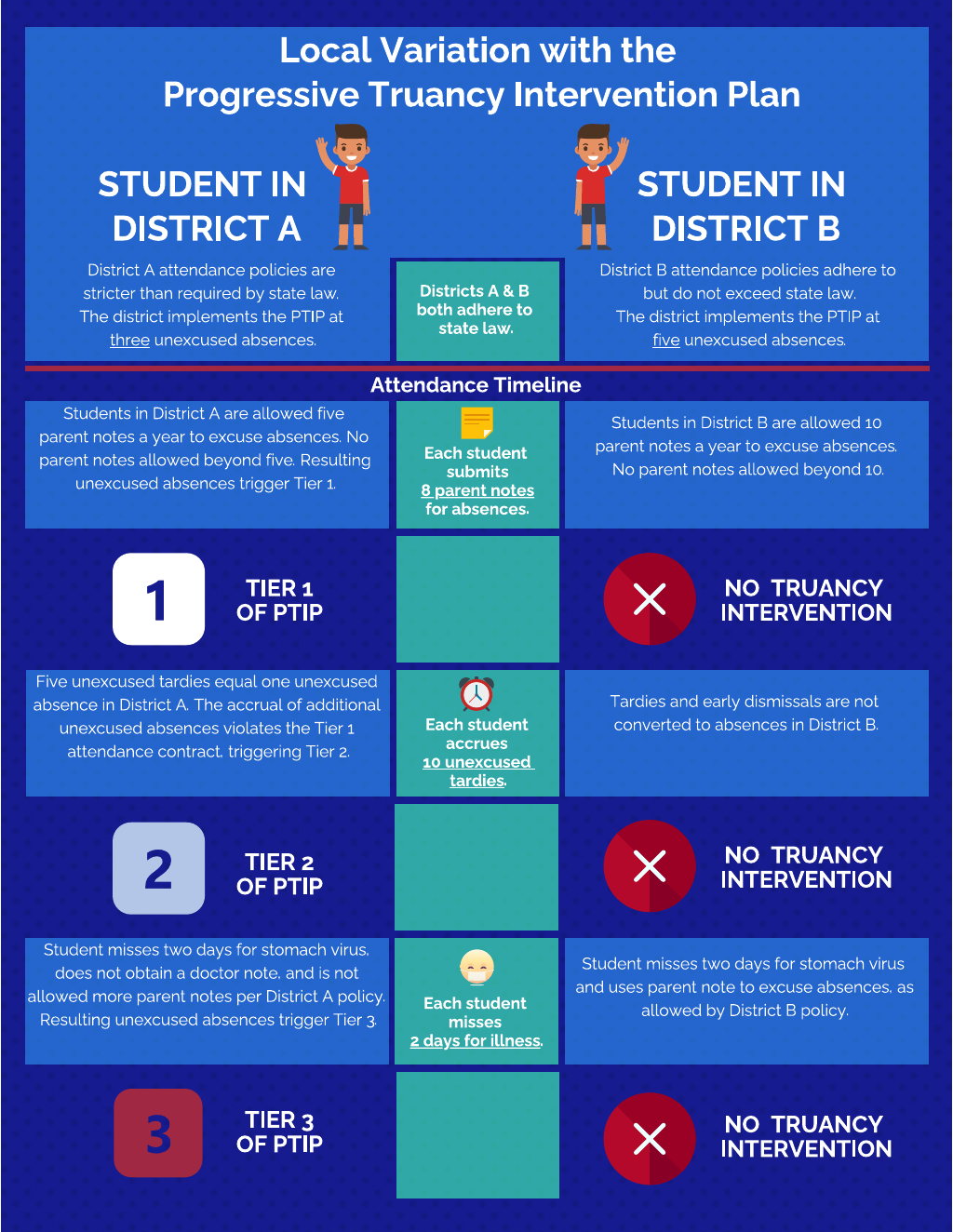

Variation in policies and practices at the district and school levels, especially for parent notes and

conversion absences, results in the inconsistent classication of absences as excused or unexcused

across the state.

Parent note policies

Conversion absence policies

Variation in local policies and practices and the inconsistent classication of absences as excused or

unexcused across the state makes analyzing and comparing district truancy data problematic. This

prevented OREA from fully evaluating the eectiveness of the progressive truancy intervention plan (PTIP).

Variation at the court level

Qualitative data used by OREA to evaluate the PTIP

State law does not address whether the PTIP should restart each school year for all students.

State chronic absenteeism rates have remained steady since 2017, the rst year chronic absenteeism was

included as an accountability measure on the State Report Card.

Students who are economically disadvantaged and students with disabilities are more likely to be

chronically absent than their peers.

High school students, especially seniors, are more likely to be chronically absent than students in

other grades.

Accountability for chronic absenteeism and for truancy are dierent. Districts and schools are held

accountable for chronic absenteeism rates, while students and parents are held accountable for

truancy rates.

Confusion exists among some school ocials about how to use alternative attendance plans for qualied

students as part of an IEP or Section 504 plan.

Policy options

The General Assembly may wish to require additional reporting by districts and schools of PTIP data and

other attendance-related data.

Number of unexcused absences required for Tier 1 of the PTIP

Number of students who move through each tier of the PTIP

Number of students referred to court for truancy and their number of unexcused absences

Number of times PTIP tiers were skipped due to lack of parent cooperation

Number of students in the PTIP based on absences from the previous school year

Parent note policy

Conversion absence policy

The General Assembly may wish to clarify certain aspects of the PTIP given confusion on the part of some

districts, schools, and juvenile courts.

Restarting tiers for all students each year

Conversion absences

The General Assembly may wish to make certain attendance-related policies more uniform for all districts

and schools.

Parent notes

Conversion absences

TDOE may wish to begin calculating truancy rates for districts and schools, taking into account local policy

and practice variations.

Juvenile courts may wish to adopt a uniform denition of truancy case and a more uniform method for

tracking truancy cases and actions taken.

Schools districts may wish to share best practices for addressing student attendance issues.

Endnotes

55

55

56

57

57

58

59

59

61

61

62

63

63

63

64

64

65

65

66

66

66

67

67

67

68

68

68

68

68

69

69

70

70

70

71

71

72

73

74

80

82

83

84

86

87

91

Appendix A: Methodology

Appendix B: Chronically Out of School Indicator

Appendix C: Chronic absenteeism of student subgroups

Appendix D: Communities in Schools

Appendix E: Driver License suspensions by county

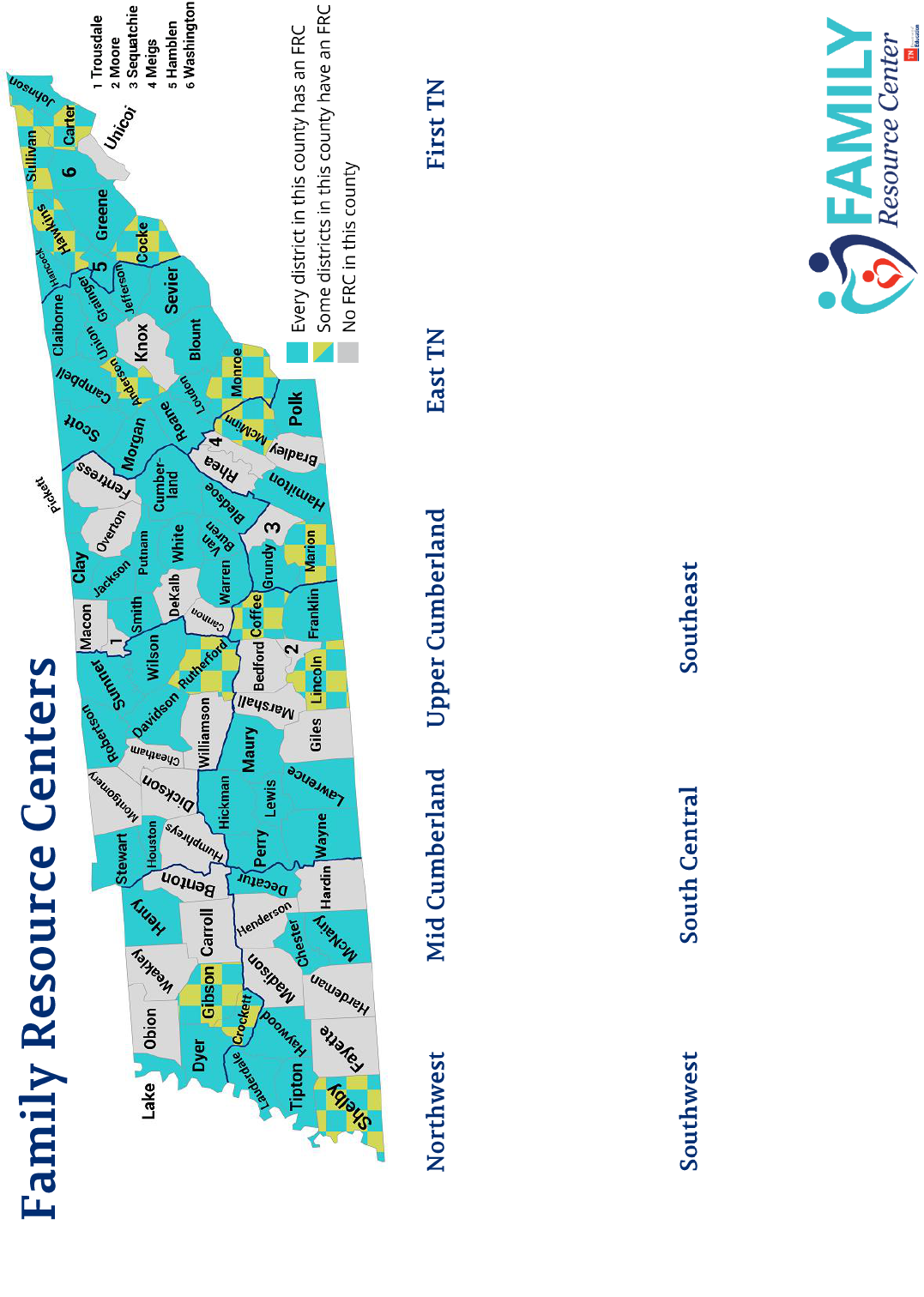

Appendix F: Family resource centers map

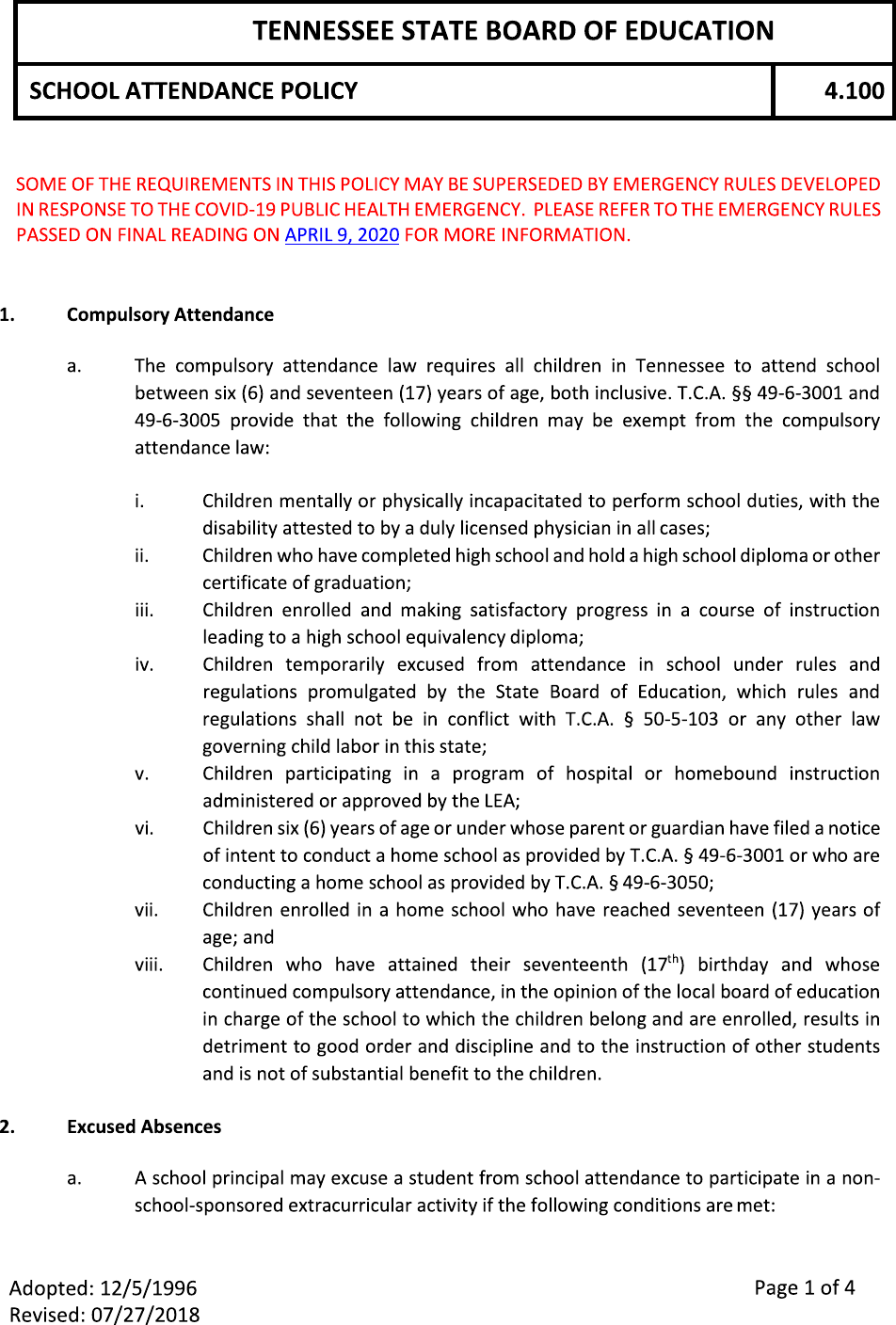

Appendix G: SBE Attendance Policy 4.100

Appendix H: TDOE Attendance Manual

5

Disclaimer

e following research is based on attendance procedures and policies in place prior to the COVID-19

pandemic. OREA administered surveys in December 2019 and January 2020; consequently, all resulting data

is based upon the respondents’ pre-pandemic experiences.

Introduction

Members of the Tennessee General Assembly requested that the Comptroller’s Oce of Research and

Education Accountability (OREA) research chronic absenteeism and truancy in Tennessee, including an

analysis of data, evaluation of districts’ use of available tools to address student absenteeism, and identication

of successful strategies. Truancy includes only unexcused absences; though not dened in law, a student is

truant in Tennessee when he or she accrues ve unexcused absences and may be subject to legal intervention.

Chronic absenteeism includes all absences, excused and unexcused; a student is chronically absent if he or

she misses 10 percent or more of instructional days per school year

(typically 18 days missed). It is possible for a student to be chronically

absent and truant, depending on the student’s total number of absences

and if the absences are excused or unexcused.

According to Tennessee Code Annotated 49-6-3001, all Tennessee

children ages six through 17 are required to attend school. is section

of code requires districts to enforce compulsory attendance laws using

various methods, up to and including referral to juvenile court. While

state law species certain steps that must be taken before attendance

becomes a legal problem, districts and schools have a great deal of

exibility in what interventions are used, what consequences imposed,

how absences are dened, and more.

ere is not a comprehensive denition of excused absences in law, and districts are able to create their own

policies regarding excused and unexcused absences within the limited parameters specied in law. In general,

excused absences are those that result from illness, a death in the family, or those for which a parent note has

been provided. An unexcused absence meets none of the criteria for an excused absence.

To meet the federal Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) requirement for a nonacademic measure of school

quality or student success, the Tennessee Department of Education (TDOE) selected chronic absenteeism

for its plan, as did many other states. As a result, districts and schools are evaluated on chronic absenteeism

annually. In addition, as of the 2018-19 school year, schools are now required by state law to use a progressive

truancy intervention plan prior to ling a petition in juvenile court for truant students.

In this report, OREA presents information about chronic absenteeism and truancy, including an explanation

of the two terms, analysis of available data, and an analysis of available tools to address student attendance.

Chronic absenteeism

Includes all absences, excused

and unexcused. A Tennessee

student is chronically absent

if he or she misses 10 percent

or more of instructional days

(typically 18 days absent).

Truancy

Includes unexcused absences

only. A Tennessee student is

truant if he or she accrues ve

unexcused absences.

6

Methodology

OREA reviewed three years of attendance data provided by the Tennessee Department of Education

(TDOE) as part of an analysis of chronic absenteeism rates. OREA also conducted a total of 52 interviews

with stakeholders from across Tennessee, including attendance supervisors, principals, and state-level

representatives. Additionally, OREA distributed online surveys to every attendance supervisor, principal, and

juvenile court judge in Tennessee. A total of 102 attendance supervisors (each representing a dierent district)

and 545 principals (representing 110 Tennessee school districts) participated in the surveys. Eighty-two

districts had representation on both surveys. Forty-three judges completed the survey, representing 43 juvenile

court districts. (Note: e boundaries of Tennessee’s 98 juvenile court districts do not always align with the

boundaries of the state’s school districts.)

A

Attendance according to Tennessee law and rule

Elementary and secondary school attendance falls under TCA 49-6-3001 et seq., which covers compulsory

attendance laws, length of school terms, attendance reporting, truancy,

educational neglect, specic excused absences, home schools, and

other subjects. e law gives the State Board of Education (SBE)

the authority to promulgate rules that prescribe guidelines for the

attendance standards and policies established by school districts. ese

districts’ policies must be rm but fair so that every student has a

reasonable chance to meet the minimum requirements. Schools must

keep parents informed of their child’s absences. e law mandates that

district attendance policies take extenuating circumstances into account,

accommodating emergencies and situations beyond a student’s control.

Students must be given a chance to appeal excessive absences and be

provided with alternative program options if minimum attendance

requirements are not met.

SBE rule states that each school district shall develop a rm but fair attendance policy. Attendance policies

must comply with TCA 49-6-3007, concerning, among other things, procedures that must be followed

for unexcused absences, and TCA 49-6-3009, concerning the development and adoption of a progressive

truancy intervention plan. Policies must address the excusing of absences for certain reasons. (See pages 6-8.)

1

Additionally, district policies should not be used to penalize students academically and attendance issues

should be resolved at the school level whenever possible. Policies must also allow students with more than ve

unexcused absences the opportunity to appeal absences, with the burden of proof resting on the student or

parent/guardian.

Compulsory attendance

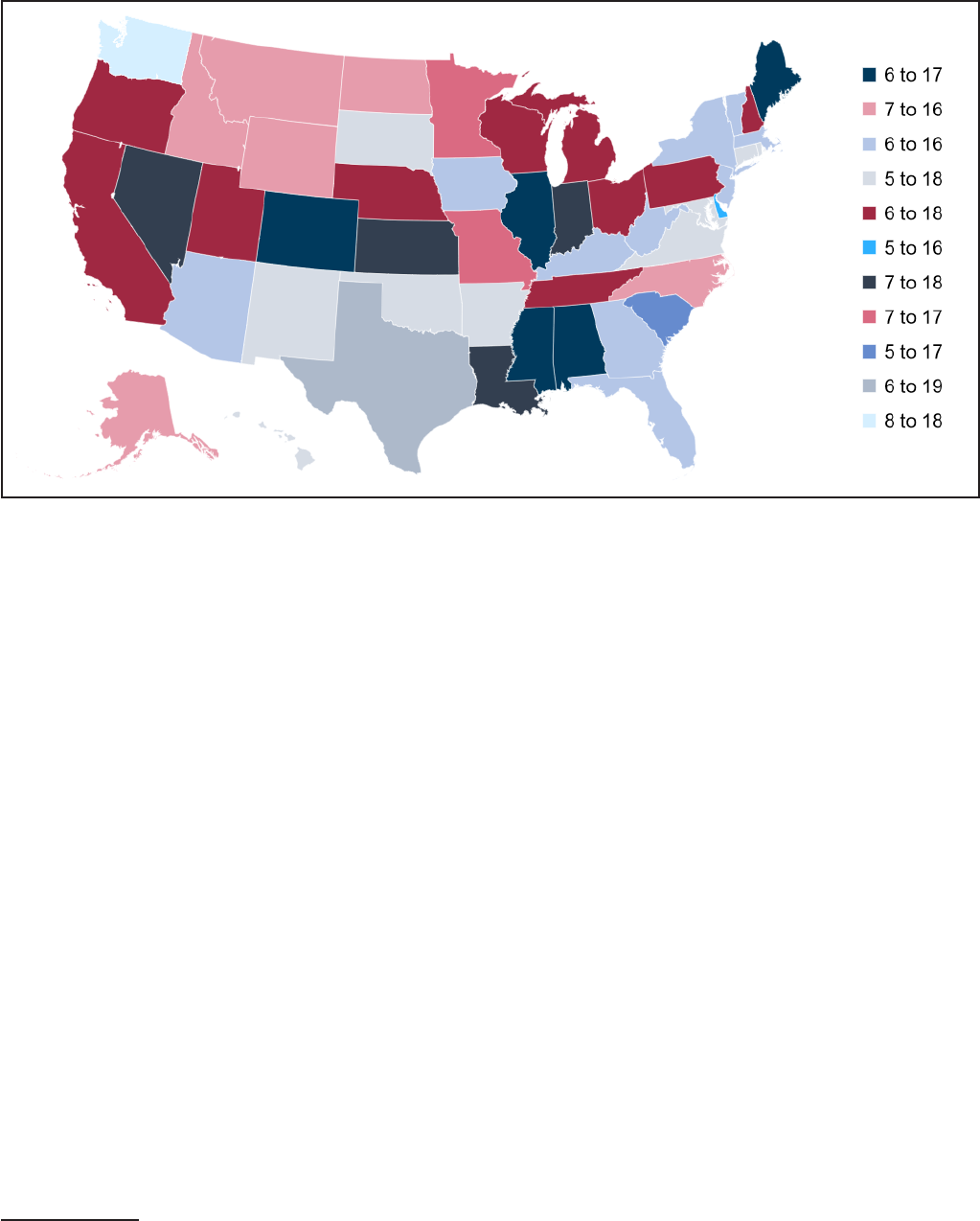

ough no federal law requires it, each state has compulsory attendance laws. As shown in Exhibit 1, the

required ages for school attendance vary by state. Twenty-ve out of 50 states (plus the District of Columbia),

including Tennessee, require children to be enrolled in school by the age of six. Once Tennessee students reach

the age of 18, whether they have completed high school or not, they are no longer required by state law to

attend school. Texas requires that students remain enrolled until they reach the age of 19 or graduate from

high school. States policies dier regarding students who fall outside the ages for compulsory attendance.

For example, Indiana law species that students must be enrolled in school by the age of seven, but if parents

choose to enroll their children earlier, they must complete the term of enrollment (e.g., if they enroll in

A

See Appendix A for more information on the methodology.

Attendance policies shall be rm

but fair.

Eective recordkeeping and

communication shall keep

parents informed of absences.

Policies shall accommodate

emergencies and circumstances

beyond a student’s control.

Students shall be given the right

to appeal excessive absences.

7

kindergarten at age six, they must nish the year). Tennessee, by contrast, allows parents who enroll a child

younger than six years old to withdraw the student within six weeks of initial enrollment without penalty.

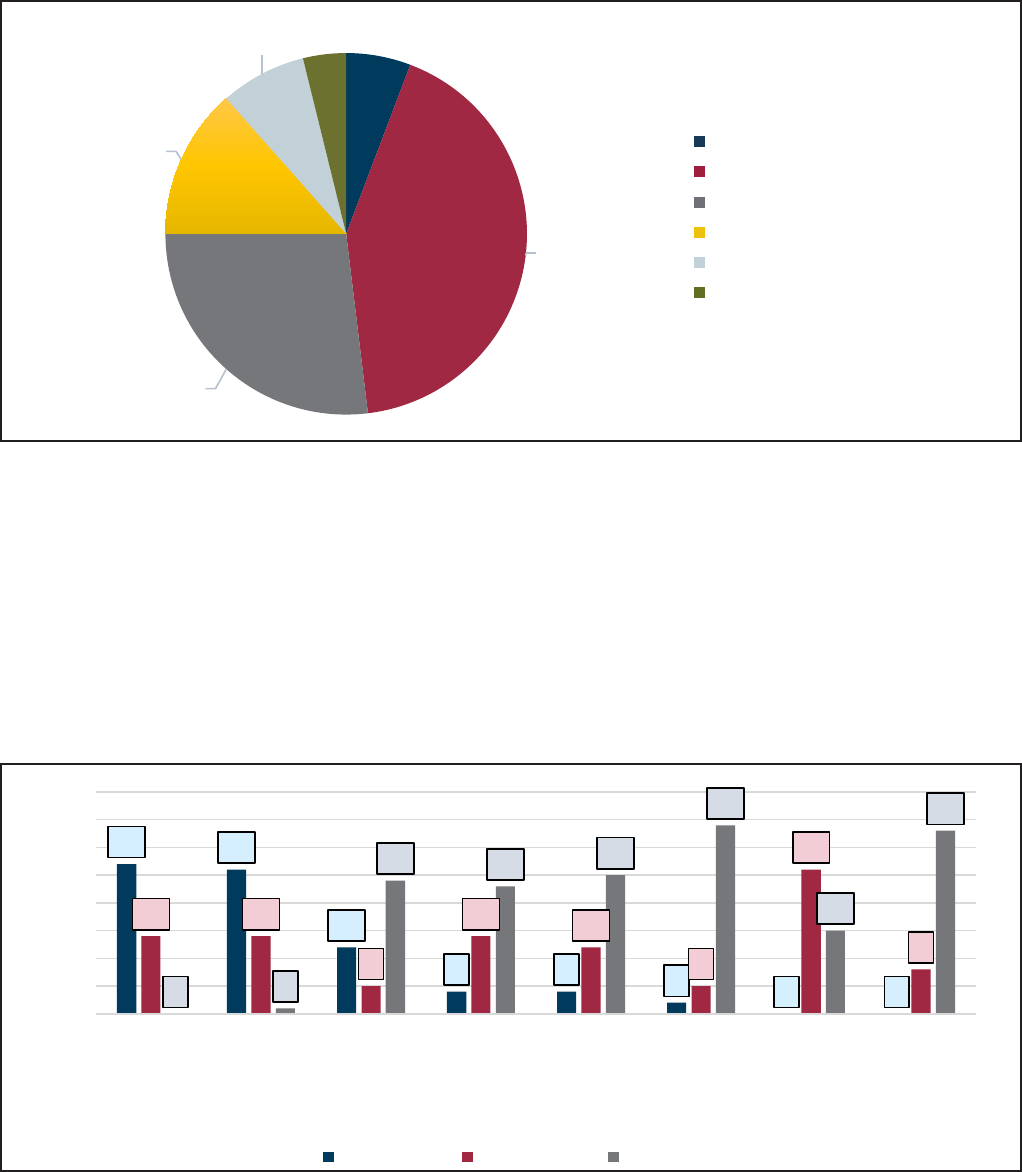

Exhibit 1: Age range of compulsory attendance laws by state

Source: Education Commission of the States, 2020.

Tennessee students under the age of 18 are not required to attend school if they meet one of the following criteria:

B

• doctor-veried mental or physical disabilities that prevent the student from performing school duties,

• completion of high school and possession of a high school diploma (or HiSET diploma),

• enrollment and satisfactory progress in course leading to HiSET diploma,

• temporary excuse that falls under SBE rules and regulations,

• enrollment in a home school, or

• determination as a detriment to the order and education of other students (applies only to those who

have reached age 17).

2

State law requires education ocials to take steps at the beginning of each school year to ensure that all

parents

C

comply with compulsory attendance laws. First, the director of schools in each district supplies

principals with a census-based list of students who fall under compulsory attendance laws. Principals must

notify the district of any students on the list who do not enroll in a public school. Private and parochial school

ocials must submit complete enrollment rosters to directors of schools within 30 days of the start of the

school year. Parents who homeschool their children must also report their intent to do so to districts on an

annual basis.

Attendance supervisors

State law requires all school districts to designate at least one qualied employee to be the attendance

supervisor for the district. State law requires attendance supervisors to assist the local school board with the

enforcement of compulsory attendance laws and to carry out other duties related to absenteeism and truancy.

Attendance supervisors are responsible for ensuring students and parents follow school attendance

B

In all cases of exemption, TCA 49-6-3005(b) requires the local school board to obtain a written recommendation for the exemption from the director of schools

and the principal of the school the student is zoned to attend.

C

is report will use the word parent in lieu of parent, guardian, or other legal custodian as written in law.

8

laws. In carrying out this responsibility, district attendance supervisors may work with school personnel to

monitor attendance data, address attendance barriers, and implement the progressive truancy intervention

plan,

D

among other duties. Attendance supervisors may also handle or assist with transportation, homebound

services, technology matters, or other responsibilities.

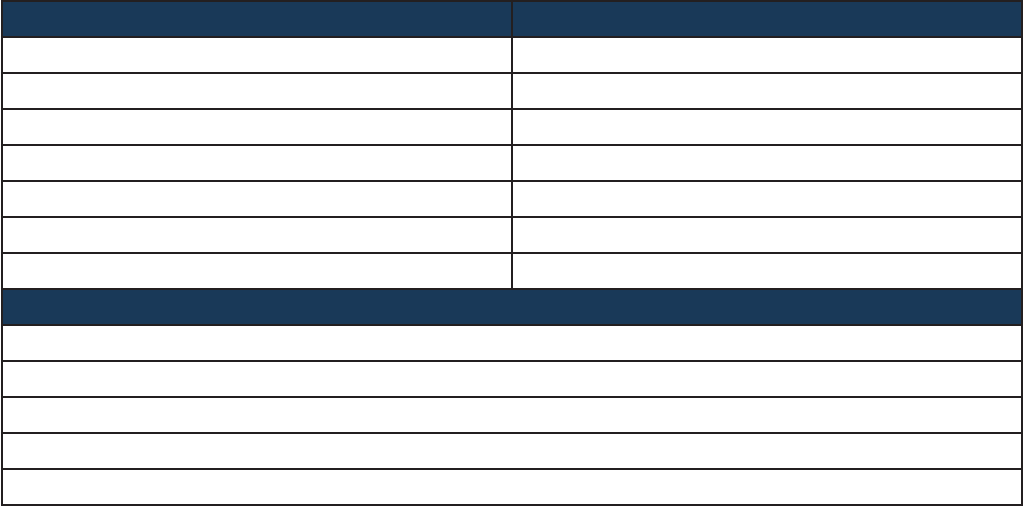

Out of 102 respondents on the OREA survey of attendance supervisors (each representing a separate district),

10 supervisors (9 percent) stated that attendance matters take up all of their time. Most supervisors (33

percent) stated that attendance takes up about half of their time, while 27 respondents (26 percent) stated it

takes up more than half of their time. Twenty-eight supervisors (27 percent) stated that it takes up less than half

of their time, and three (3 percent) indicated that attendance takes very little of their time.

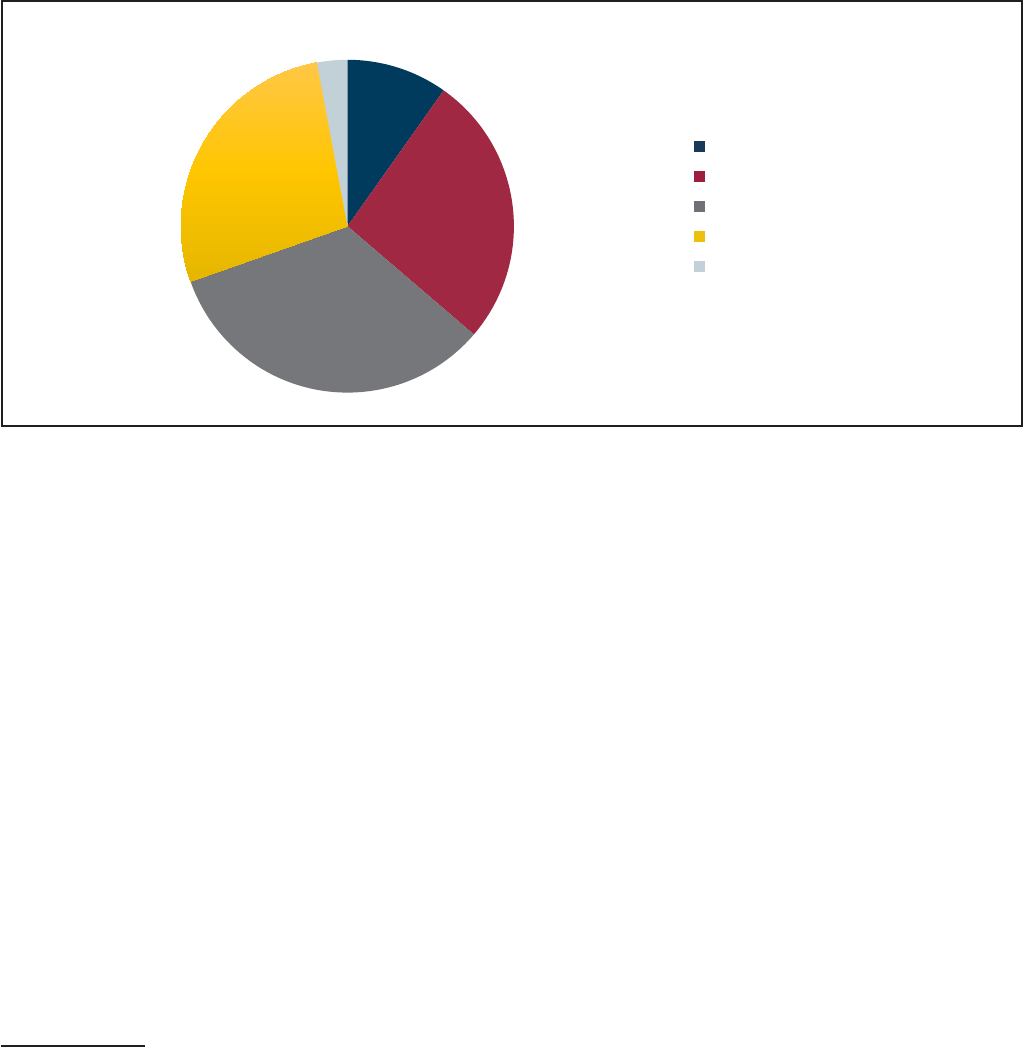

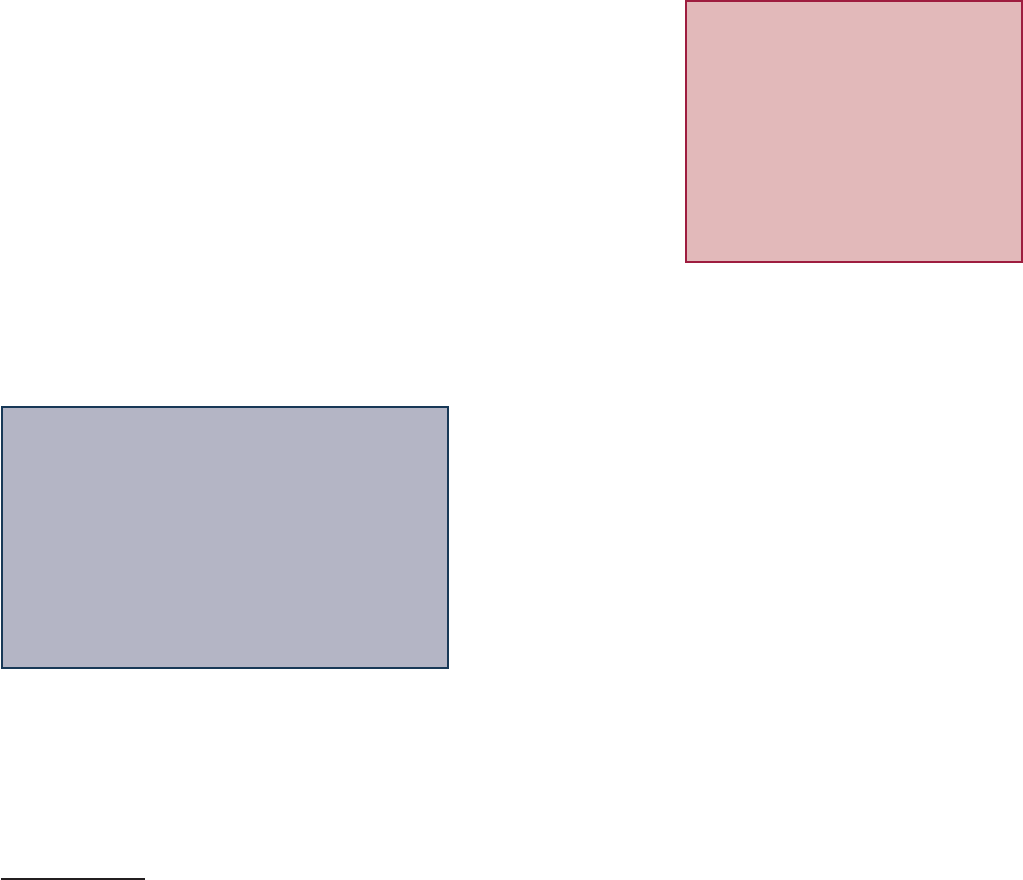

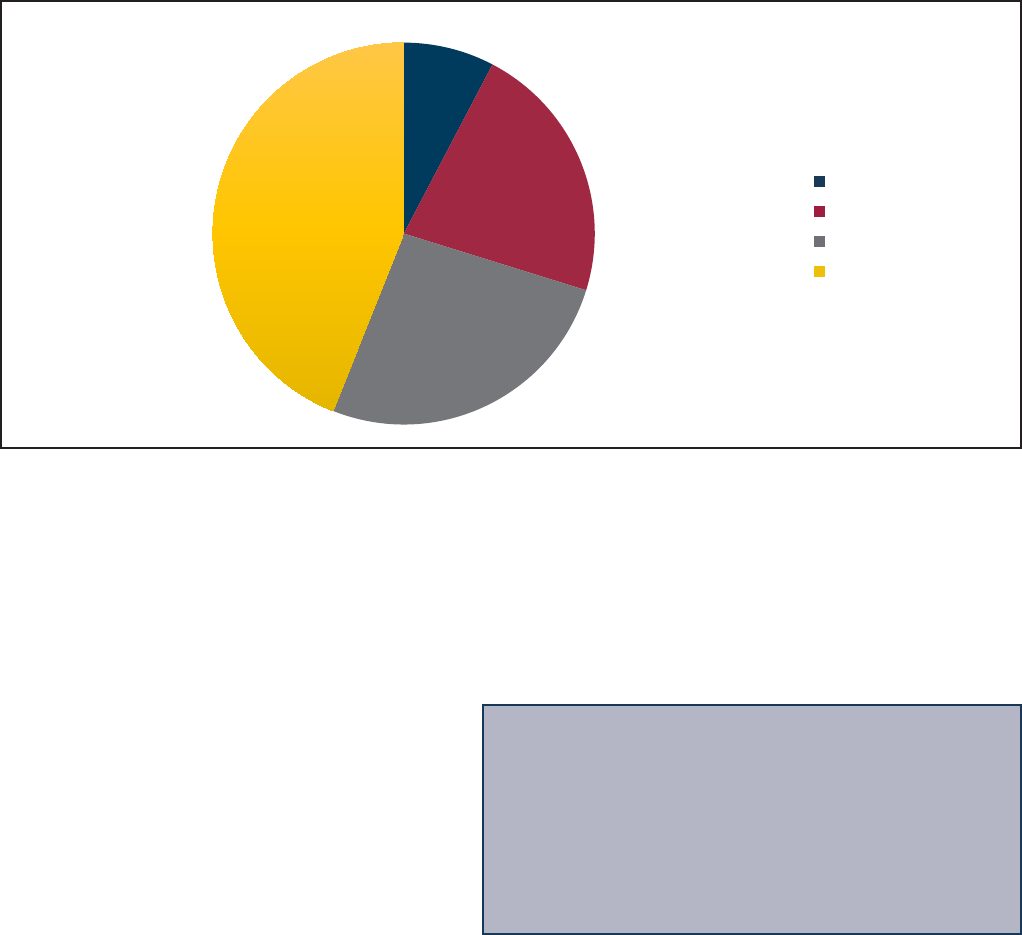

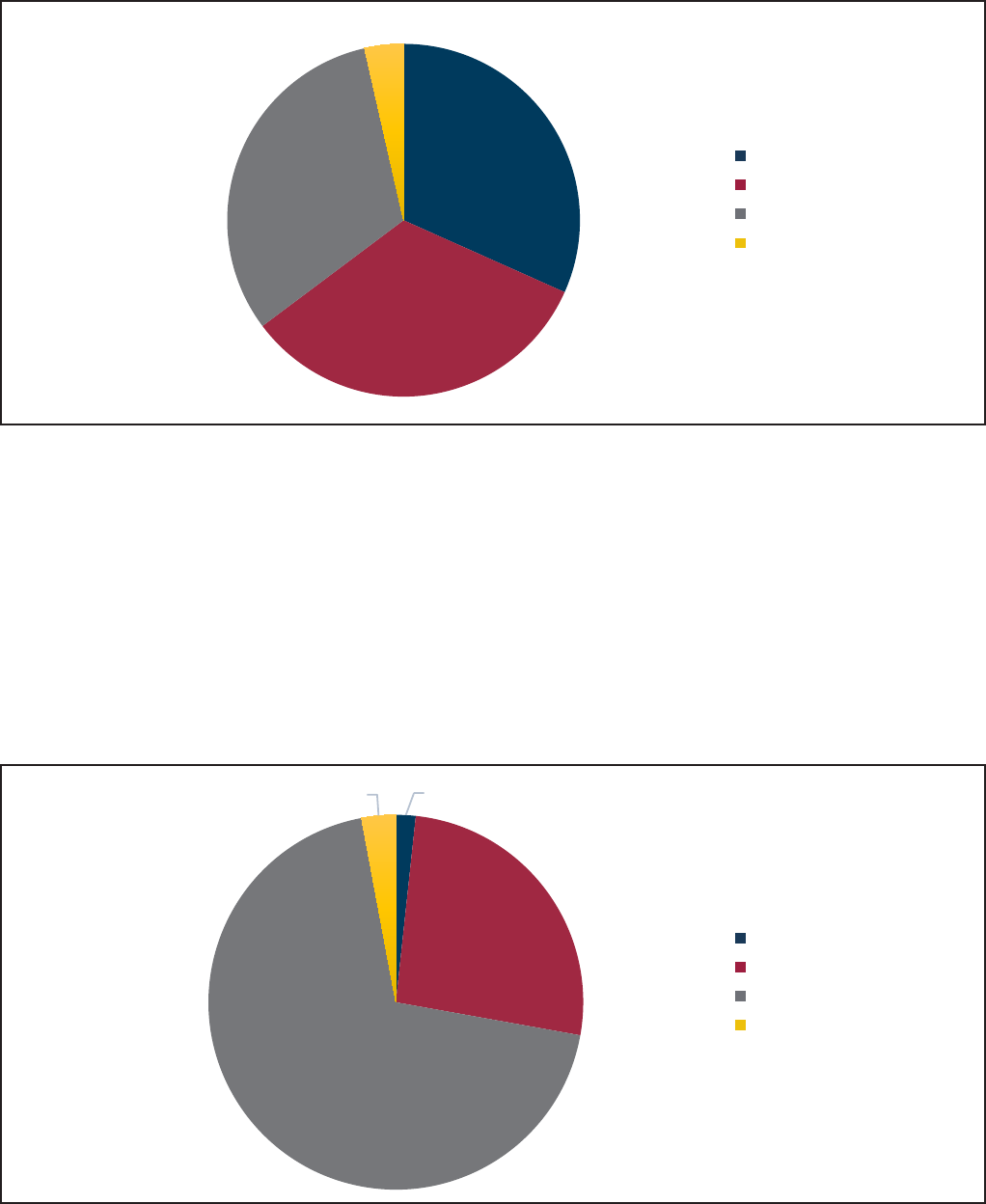

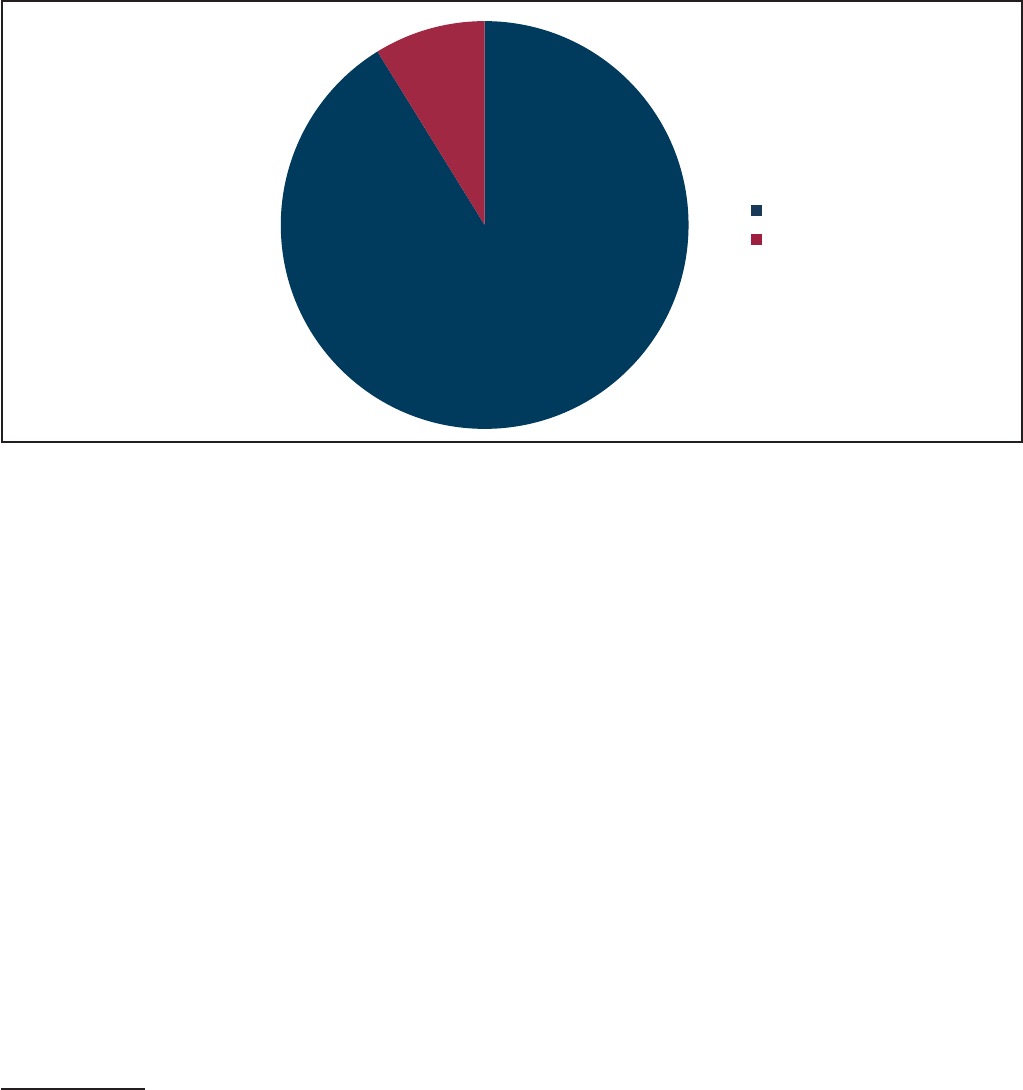

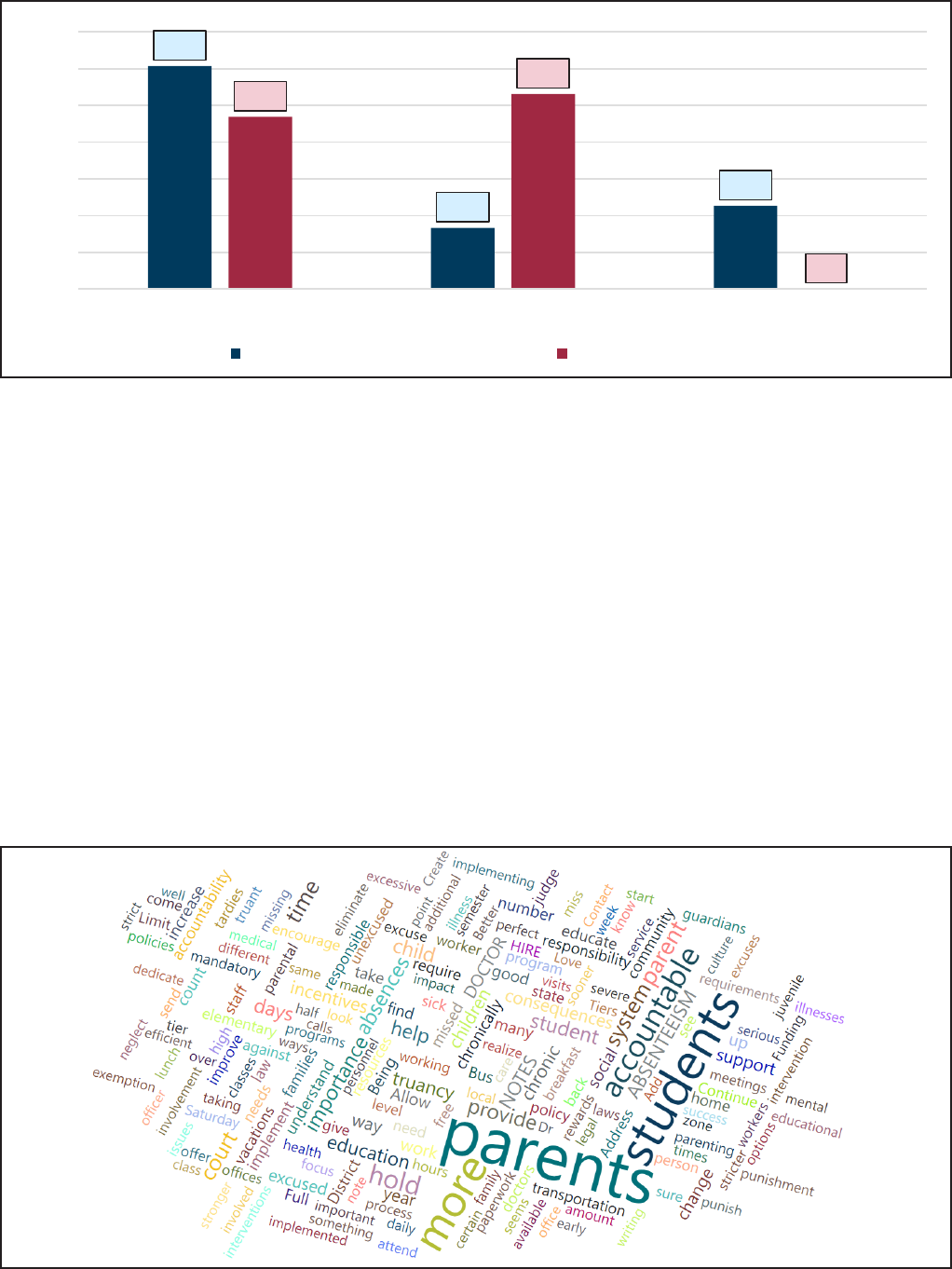

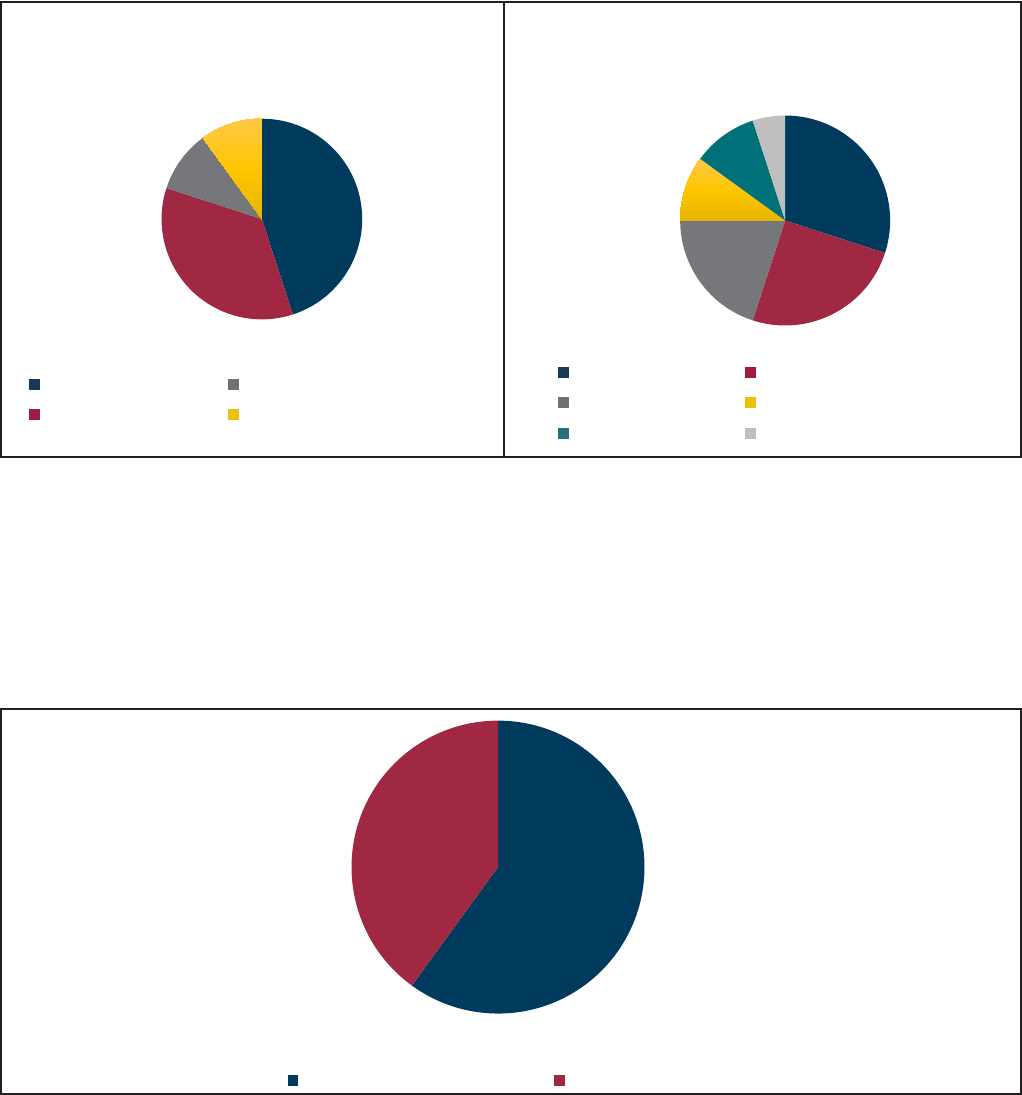

Exhibit 2: Attendance supervisors’ time spent on attendance (n=102)

Source: OREA survey of attendance supervisors, December 2019.

Attendance supervisors who are responsible for monitoring systemwide attendance data rely on school-level

sta for accurate attendance data. From the teacher who takes roll to the attendance clerk who records late

arrivals of students (commonly called “tardies”), several dierent sta members play a role in the attendance

recording process within a school.

Support sta for attendance supervisors

Most districts employ at least one sta member to assist the attendance supervisor in the review of attendance

data, enforcement of attendance policies, and other attendance-related responsibilities. Larger school districts

are more likely to employ multiple support sta, while smaller districts may rely solely on the attendance

supervisor to complete all aspects of the job.

Attendance support sta may also be present at the school level. On the OREA survey, principals reported

that attendance support sta at the school level may include social workers, licensed counselors/mental health

professionals, school counselors, nurses, and Communities in Schools coordinators.

E

Principals indicated that the support sta with the highest rates of full-time availability are school counselors

(79 percent of respondents) and nurses (73 percent of respondents). Some respondents emphasized that a sta

member’s availability aects his or her ability to measurably impact student attendance.

D

e progressive truancy intervention plan, as described in TCA 49-6-3007, requires districts to move students through three tiers of interventions aimed at

addressing attendance barriers before referring them to juvenile court, if necessary.

E

See pages 52-53 for more information about Communities in Schools.

10, 10%

27, 27%

34, 33%

28, 27%

3, 3%

All of my time More than half of my time About half of my time

Less than half of my time Very little of my time

All of my time

More than half of my time

About half of my time

Less than half of my time

Very little of my time

27%

9

Local attendance policies

Attendance policies and procedures vary widely across the state and, in some cases, among schools within

a district. OREA reviewed the attendance policy posted on the website of each district in Tennessee. e

website of some districts included multiple attendance policies, and in some cases the posted attendance policy

had not been updated to incorporate the progressive truancy intervention plan requirement established by

a 2017 state law. (See page 31 for more information on the progressive truancy intervention plan.) rough

interviews with attendance supervisors, OREA found that, for some districts, the attendance policy posted

online diers from the policy in use.

Of the nearly 150 local board policies pulled from district websites and reviewed by OREA, 128 used the

model policy provided by the Tennessee School Boards Association (TSBA).

F

Of those 128 districts, some

posted other attendance policies on their websites in addition to the TSBA model policy.

Depending on the district, specications within attendance policies are determined at either the district or

school level. Some districts grant principals discretion to set policy at the school level, while other districts

set blanket policies that every school in the district is expected to follow. Most principals who responded to

the OREA survey indicated they have discretion to implement school-specic procedures regarding excused

absences (i.e., determining what absences are excused outside of what is specied in district policy and what

discipline will be issued for attendance oenses).

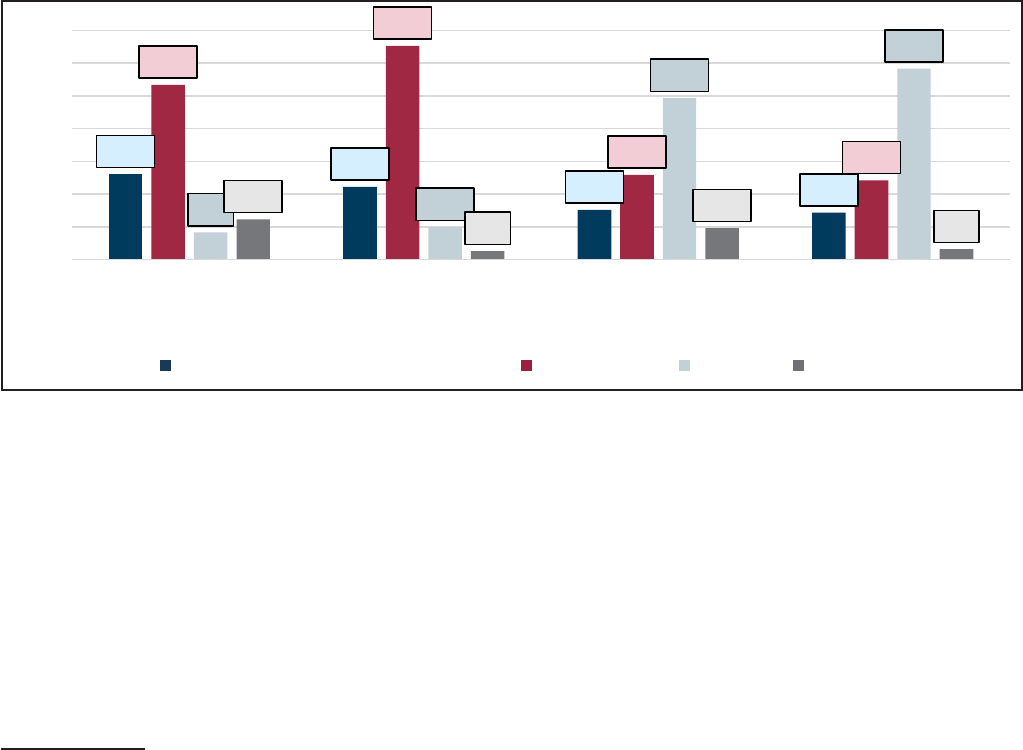

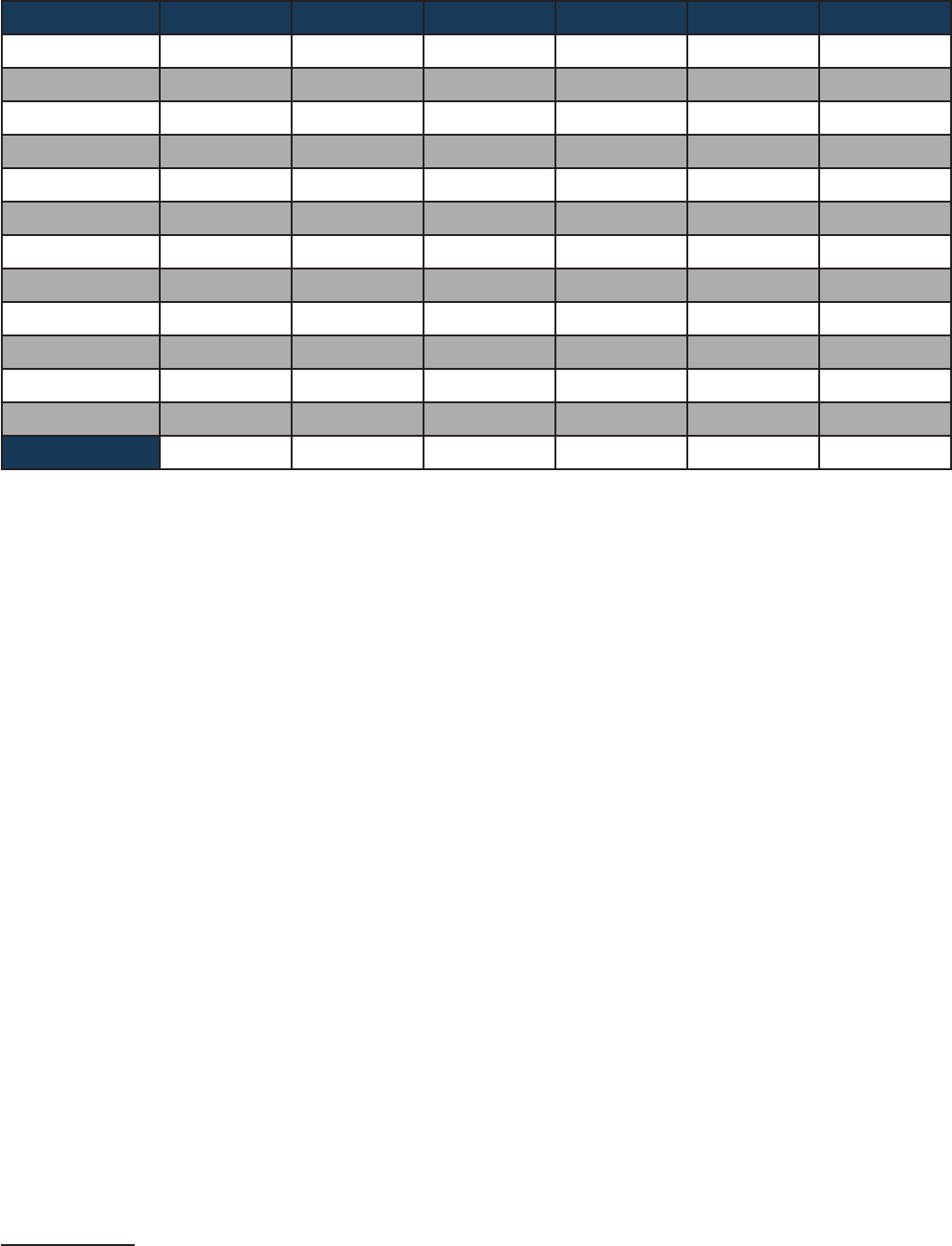

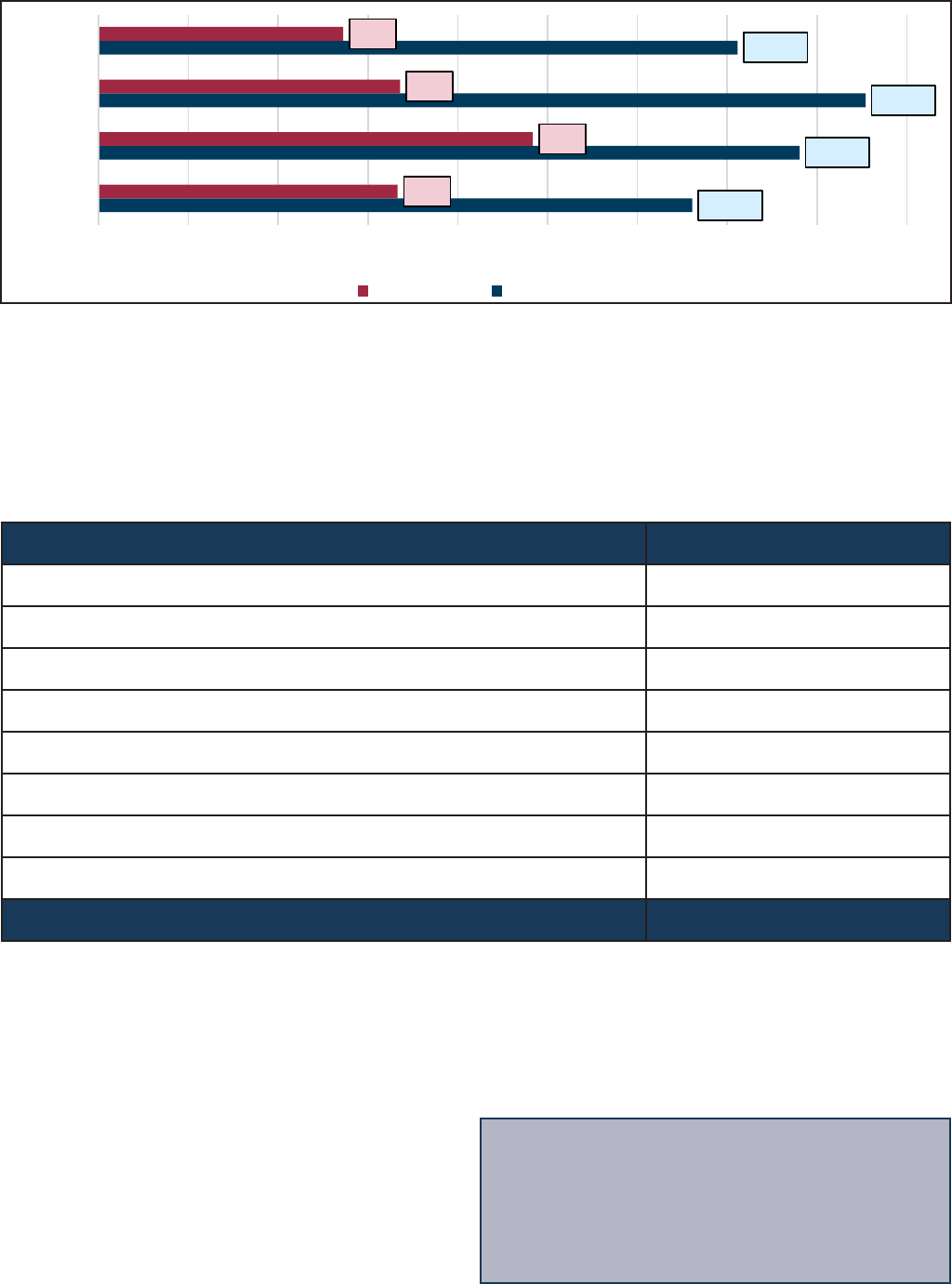

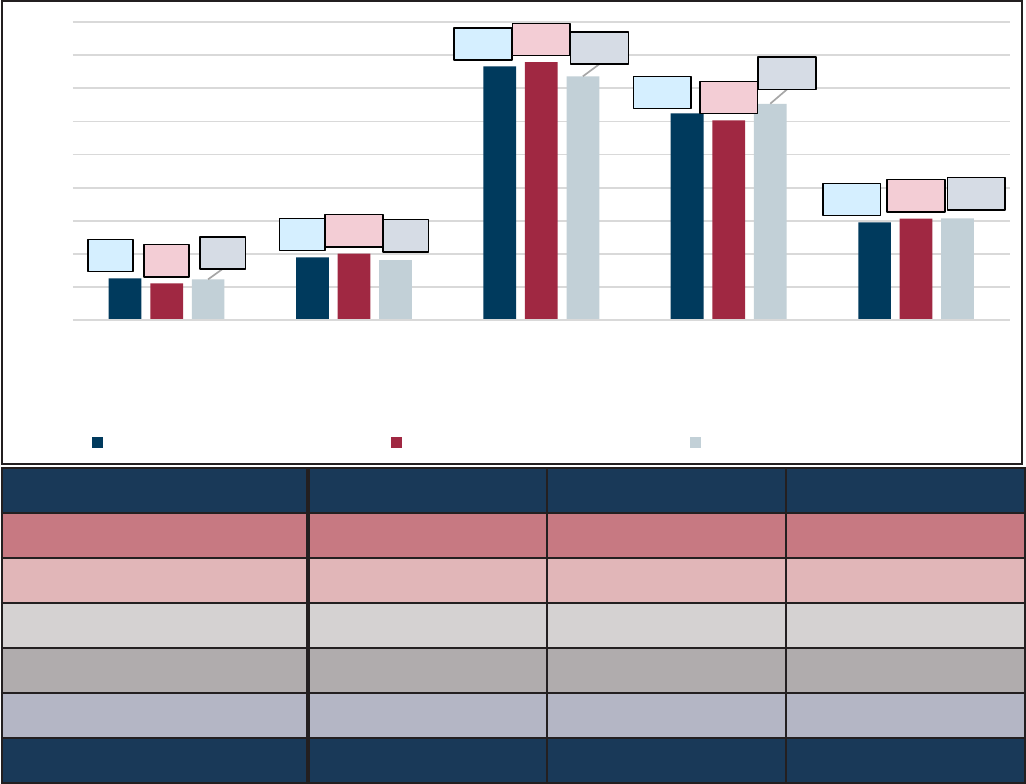

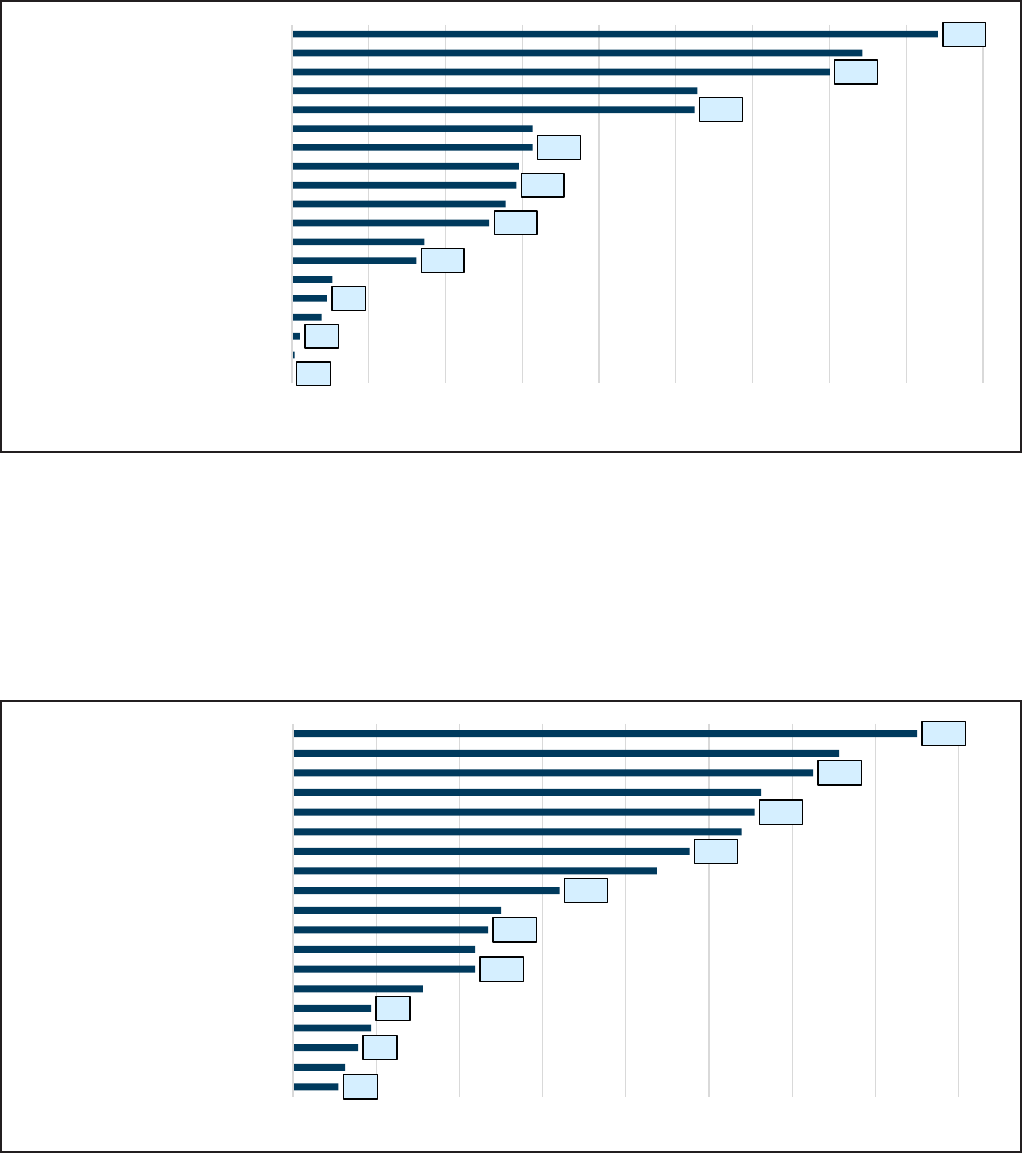

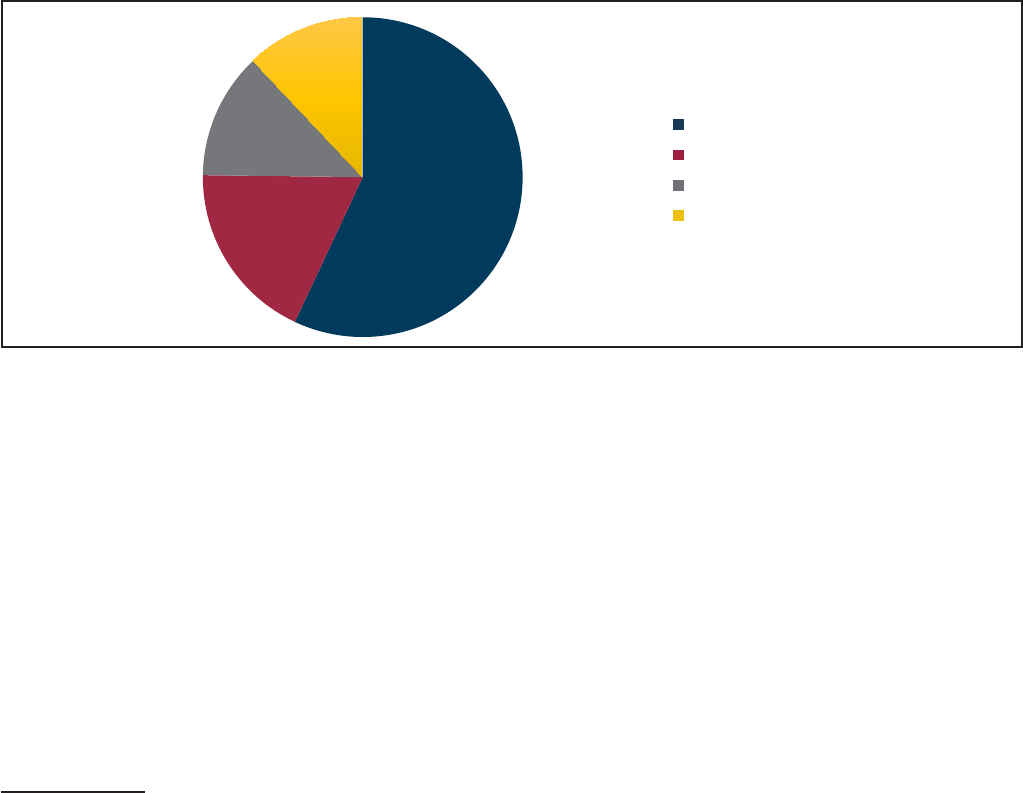

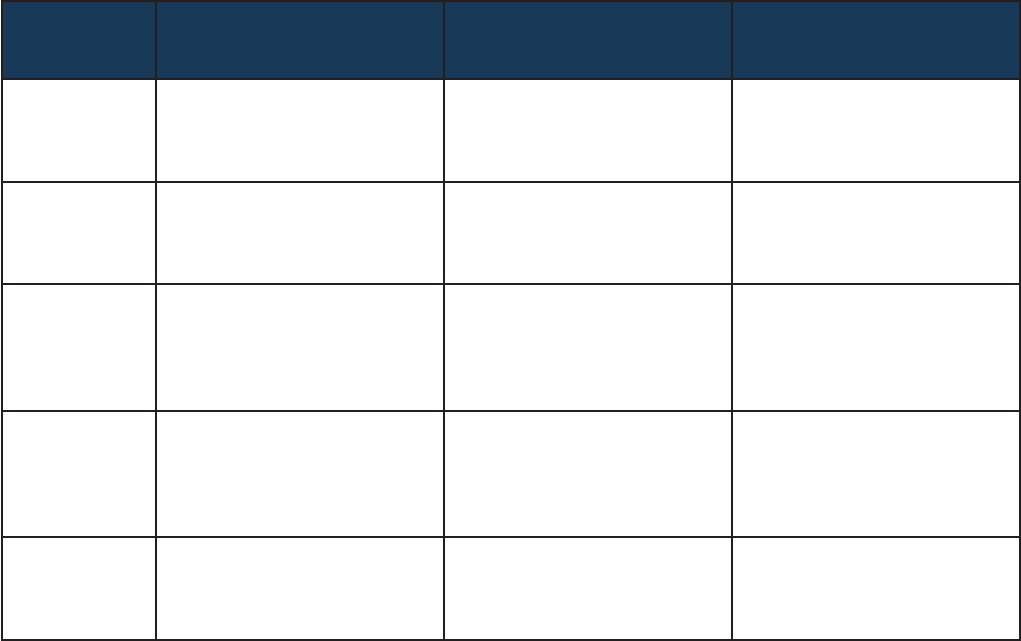

Exhibit 3: Who determines certain attendance policies? (n=545)

Note: Numbers may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

* Conversion absences are absences formed through the accrual of a set number of tardies and/or early dismissals.

^ Parent notes are notes provided by parents to excuse their child’s absence from school for such reasons as illnesses that do not require a visit to the doctor, family emergencies, and

vacations. School districts have dierent policies regarding parent notes. In most districts, students are allowed to provide a limited number of parent notes to excuse absences for medical or

personal reasons. Such policies are usually set at the district level with varying allowances for principal discretion.

Source: OREA survey of principals, December 2019.

Excused versus unexcused absences

e designation of absences as excused or unexcused determines whether a student is chronically absent, truant,

or both. Tennessee law allows for excused and unexcused absences to be dened primarily by school districts,

and, in some cases, at the school level. e law does not dene the term “unexcused absence.” As for excused

absences, the law species three circumstances for which districts are required to excuse a student’s absence

from school: (1) absences for work as an election ocial; (2) absences for court-related matters; and (3)

absences related to a parent’s service in the U.S. Armed Forces. (See Exhibit 4.)

F

is gure includes all 141 county, municipal, and special school districts, ve state special schools (Alvin C. York Institute, Tennessee School for the Blind,

Tennessee School for the Deaf-Knoxville, Tennessee School for the Deaf-Nashville, and West Tennessee School for the Deaf), the Achievement School District

(ASD), the State Board of Education (SBE), and the Tennessee Department of Children’s Services (DCS). e ve state special schools, ASD, SBE, and DCS are

treated as school boards in terms of creating their own policies for the school(s) within their jurisdiction.

26%

22%

15%

14%

53%

65%

26%

24%

8%

10%

49%

58%

12%

3%

10%

3%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

Conversion absences* Parent notes^ Discipline for

attendance matters

Excused absences

(outside of board

policy)

Director of schools/other district staff School board Principal Other

Director of schools/other district sta School board Principal Other

10

In 2020, Public Chapter 743 required public schools to excuse students from school for released time courses

in religious moral instruction for up to one hour each day upon the request of a student’s parent, regardless of

whether the school district has adopted such a policy.

G

Additionally, principals may excuse up to 10 absences

for participation in extracurricular activities that are not school-sponsored (e.g., travel sports teams, dance

competitions, etc.). e law also mandates that students serving as pages in the General Assembly are counted

as present in school and not assigned an excused or unexcused absence.

Exhibit 4: Absences counted as excused or present by Tennessee state law

Note: Students who are absent for certain reasons may also be counted as present per State Board of Education policy.

Source: Tennessee Code Annotated.

e State Board of Education (SBE) requires districts to adopt rm but fair policies that are in accordance

with the SBE’s School Attendance Policy 4.100, state law, and the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act.

3

e TDOE Attendance Manual, last updated in 2020, echoes the specications found in state law and SBE

rule.

Under SBE authority, the manual lays out which students should be counted present even when missing

traditional instruction time: students serving in-school suspension (and receiving educational services);

homebound students receiving homebound services; alternative school or program students; students serving

as pages for the General Assembly; and students participating in school-sponsored events. e manual

instructs districts to adopt a policy regarding excused and unexcused absences in compliance with SBE’s

School Attendance Policy 4.100, but no standard denitions are supplied.

G

Released-time courses for religious moral instruction take place during the school day but must not be funded by taxpayer funds or occur on school property. A

released time program operated in Knox County during the 2018-19 school year. Participating students left school for an hour per week, usually missing art or music

classes, and were transported to a church for religious activities and instruction.

TCA Excused absences required by law

2-4-103(e)

A county election commission may appoint as an election ocial any qualied person who

has reached the age of 16. High school students are entitled to an excused absence when

serving as a poll ocial as well as compensation.

49-2-130

Upon the request of a student’s parent, school districts are required to excuse a student from

school to attend a released time course in religious moral instruction for up to one hour during

each school day, regardless of whether the district has adopted such a policy as long as other

requirements specied in law are met.

49-6-3002(c)(1) Absences for court-related matters must be excused and makeup work allowed.

49-6-3019

A student whose parent is in the U.S. Armed Forces is allowed: 1.) an excused absence for

one day when the member is deployed; 2.) an additional excused absence for one day when

the service member returns from deployment; 3.) excused absences for up to 10 days for

visitation when the member is granted rest and recuperation leave and is stationed out of the

country; and 4.) excused absences for up to 10 days cumulatively within the school year for

visitation during the member’s deployment cycle.

TCA Excused absences allowed by law

49-6-3022

Principals may excuse up to 10 absences for participation in non-school-sponsored

extracurricular activities if the student provides documentation of proof of participation and

submits a written request no later than seven business days prior to the absence.

TCA Absences counted as present according to law

49-6-3018

Children who serve as pages of the General Assembly during the school year shall be

counted as present, as neither an excused nor unexcused absence, in the same manner as

an educational eld trip.

11

e TSBA attendance policy template complies with SBE requirements with more specications about

excused absences, though the term is not explicitly dened. e TSBA template states that “absences shall be

classied as either excused or unexcused as determined by the principal/designee.” e reasons for excusing

an absence listed in the TSBA template mirror those listed in the attendance policies of most schools. ese

reasons include:

• personal illness/injury,

• illness of immediate family member,

• death in the family,

• extreme weather conditions,

• religious observances,

• pregnancy,

• school-endorsed activities,

• summons, subpoena, or court order, or

• circumstances which in the judgment of the principal create emergencies over which the student has

no control.

Parent notes

Most districts allow a limited number of parent notes to excuse absences

for such reasons as vacations, family emergencies, or illnesses that do

not require a visit to the doctor. Students may excuse no more than ve

absences per year with a parent note in most of the districts and schools

represented on the OREA surveys. Some districts and schools allow

students to excuse up to 10 absences per year (or in some cases ve per

semester) with a parent note. Four attendance supervisors said that in

each of their districts the number of parent notes allowed is decided by

principals at the school level. In other districts, the number of parent

notes allowed is set at the district level and varies by grade level. In these

districts, the upper grades are allowed fewer notes than the lower grades;

three of these districts do not accept parent notes for middle and/or high school students.

It is possible for students to reach the level of chronic absenteeism with all or most of their absences excused

by parent notes. e majority of respondents on OREA

surveys, over two-thirds of attendance supervisors and

principals (395 respondents), indicated it was common for

chronically absent students to have an excessive number

of absences excused by parent notes. In some cases,

students may accrue enough unexcused absences to start

the progressive truancy intervention plan (PTIP)

H

but are

allowed by school ocials (or potentially juvenile court

judges) to bring in retroactive notes to excuse absences that

were previously unexcused.

Some districts plan to adjust their parent note policies to limit the number that may be used per year to curb

excessive use by parents. Other districts with the same issue indicated they may no longer accept parent notes

for students at certain grade levels, while others are considering no longer accepting parent notes.

H

e progressive truancy intervention plan, as described in TCA 49-6-3007, requires districts to move students through three tiers of interventions aimed at

addressing attendance barriers before referring them to juvenile court, if necessary.

Districts allow varying numbers of

parent notes to excuse absences

for vacations, family emergencies,

minor illnesses, and more.

Two-thirds of attendance

supervisors and principals cited

excessive parent notes as a

common factor in their students’

chronic absenteeism.

Some districts vary parent note policies by

grade level.

"Elementary schools are allowed ve per

semester. Secondary schools are allowed

three per semester. We are planning to change

our policy for elementary to be the same as

our secondary policy."

Respondent to OREA survey of attendance supervisors, Dec. 2019

12

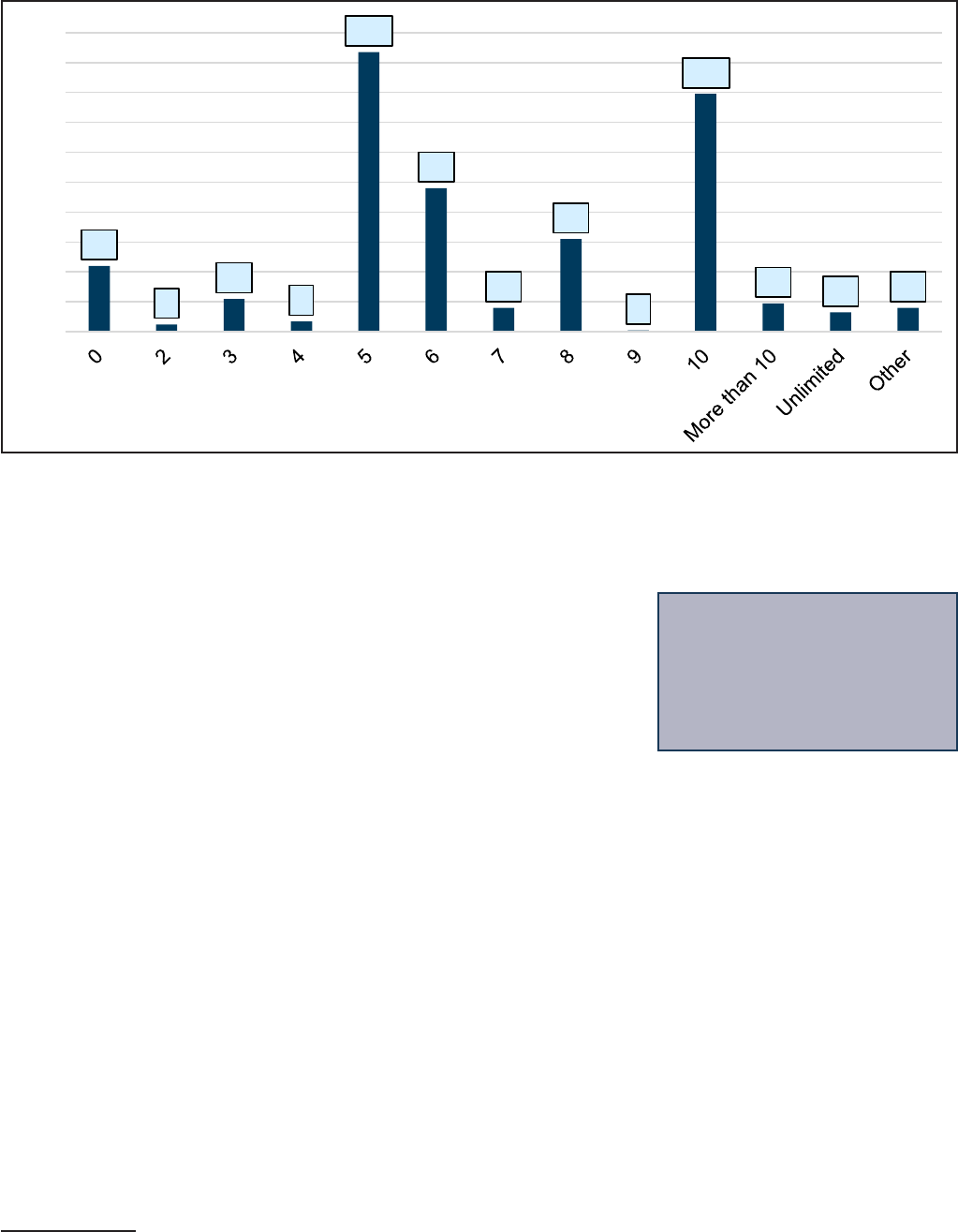

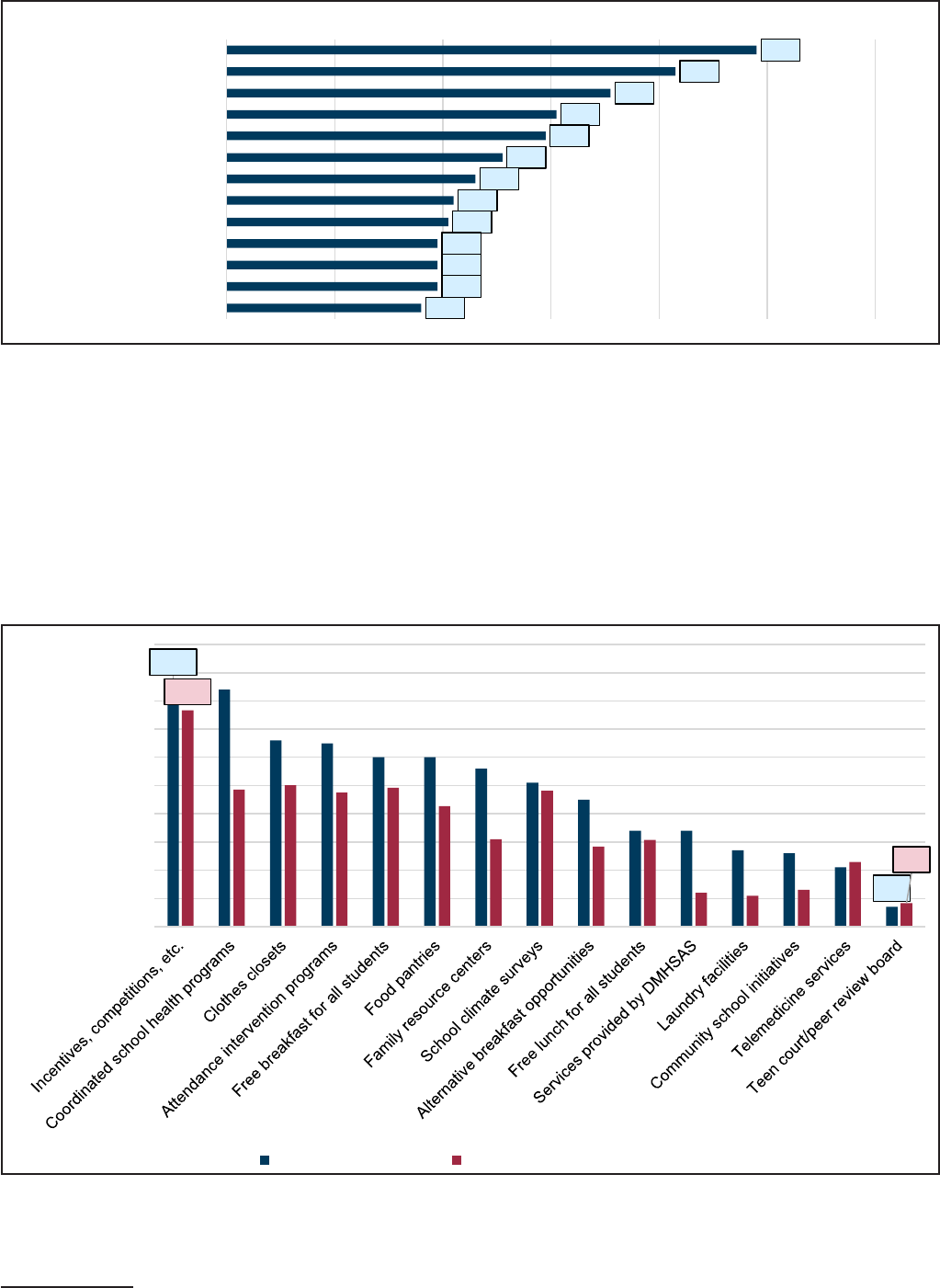

Exhibit 5: Number of parent notes allowed by district, according to attendance supervisors

and principals (n=647)

Note: is chart combines survey results from attendance supervisors and principals. e survey responses diered slightly between the two groups but may be

explained by factors relative to grade level, principal discretion, etc.

Source: OREA surveys of attendance supervisors and principals, December 2019.

Conversion absences

Repeatedly arriving late to school and/or leaving early results in missed

instructional time for students. Some districts and schools discourage

students’ late arrivals and early departures by converting a set number

of late arrivals to school (or tardies) and/or early dismissals to absences

(hereafter referred to as conversion absences

I

). For example, a district

may assign one unexcused absence to a student who accumulates ve

unexcused tardies.

J

On OREA surveys, 43 percent of supervisors (each representing a dierent district) and 57 percent of

principals indicated their districts neither allow conversion absences nor do they allow principals to institute

such policies. Where such policies are allowed, implementation varies from district to district and often from

school to school. Twenty-eight supervisors (27 percent) said that all schools in their districts follow a blanket

policy for conversion absences. Another 29 percent of supervisors (30 respondents) stated their districts do not

have a blanket policy, leaving such decisions to principals. In such cases, conversion absences may be issued in

some but not all of a district’s schools.

Some districts convert tardies into either excused or unexcused absences. Sixty-four percent of supervisors

and 35 percent of principals who indicated their districts’ policies permit conversion absences indicated that

only those tardies and early dismissals that are unexcused are converted, and then only to unexcused absences.

Eighteen percent of supervisors (six respondents) and 30 percent of principals (71 respondents) stated that

unexcused tardies and/or early dismissals are converted to unexcused absences while excused tardies and/or early

dismissals are converted to excused absences. Some respondents indicated that all tardies and early dismissals,

whether excused or unexcused, are converted to unexcused absences.

I

OREA uses the term conversion absences to refer to absences that result from the accrual of a set number of tardies and/or early dismissals, as determined by district

or school policy.

J

According to the TDOE Attendance Manual, students in grades pre-k through 12 must be present for at least 50 percent of the scheduled school day to be counted

present for state reporting purposes, including on abbreviated school days.

Conversion absences are

absences that result from the

accrual of a set number of

tardies and/or early dismissals,

as determined by district or

school policy.

44

5

22

7

187

96

16

62

1

159

19

13

16

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

13

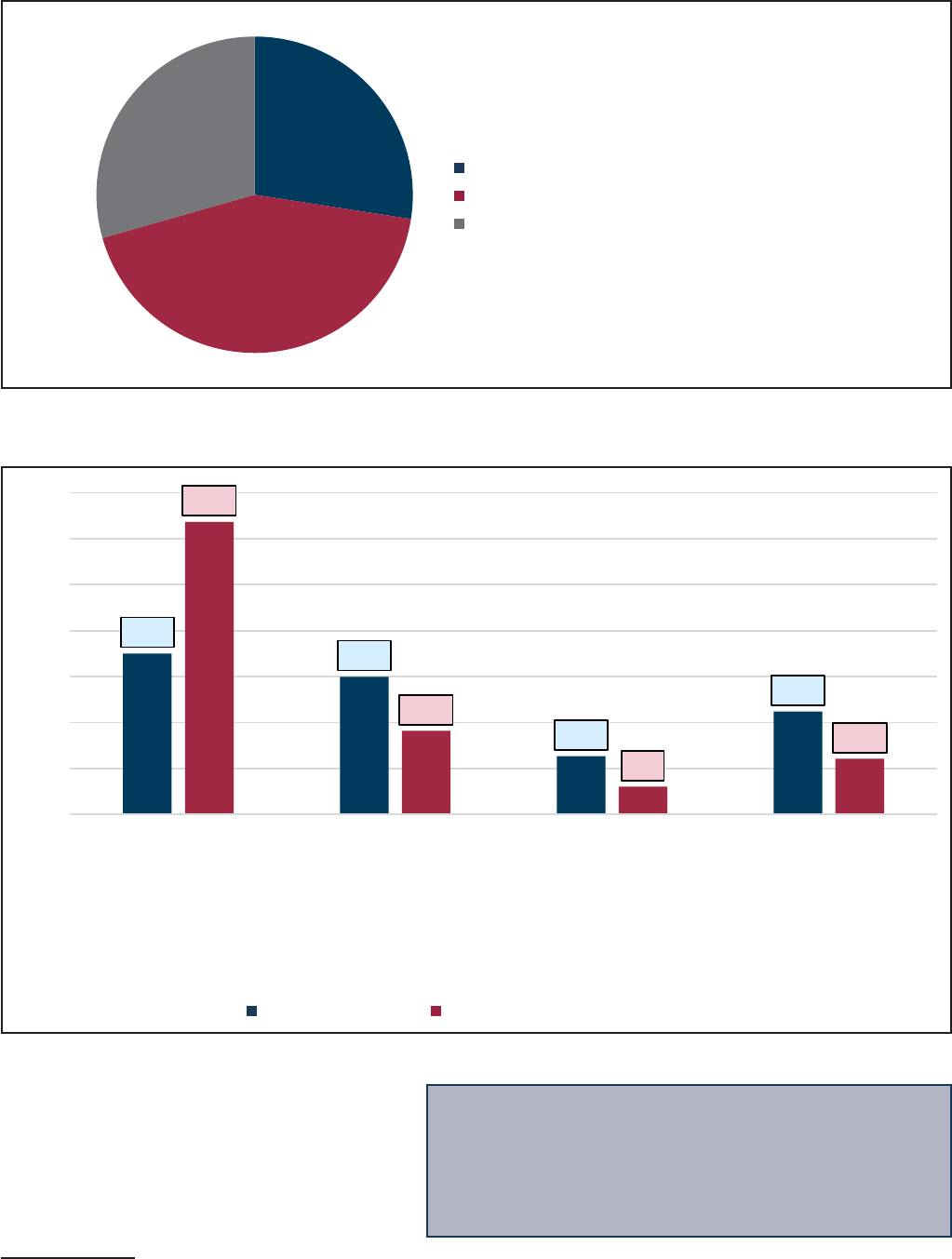

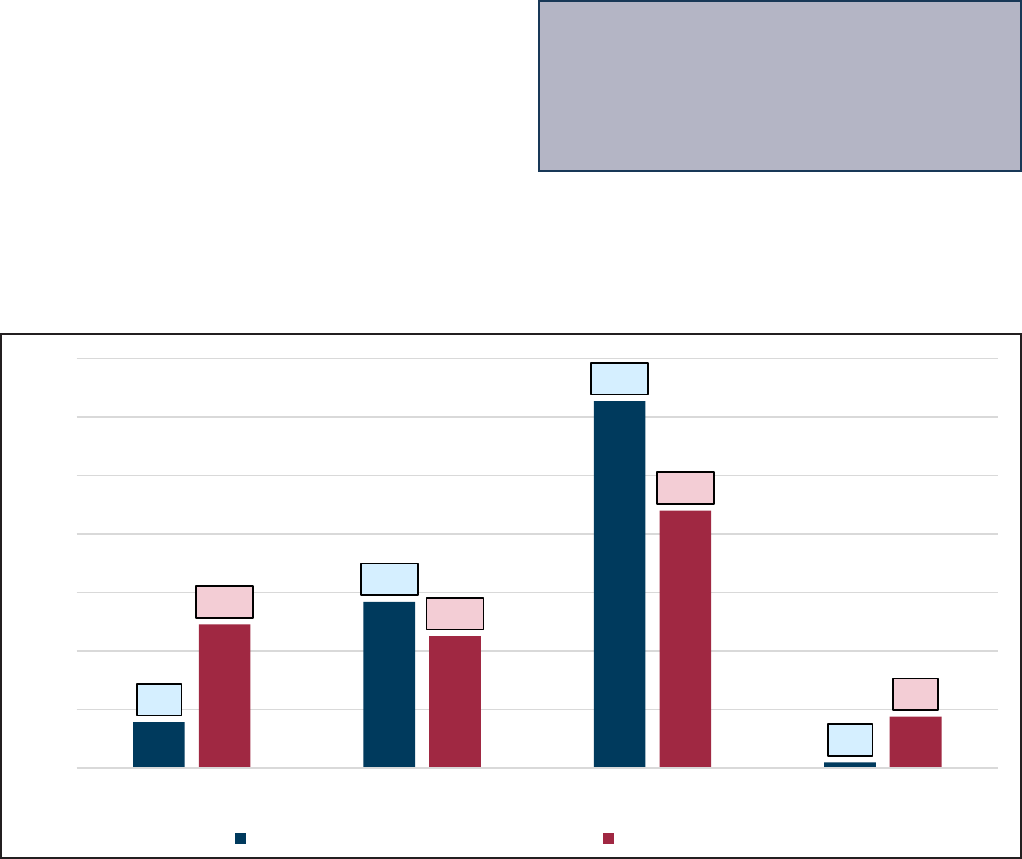

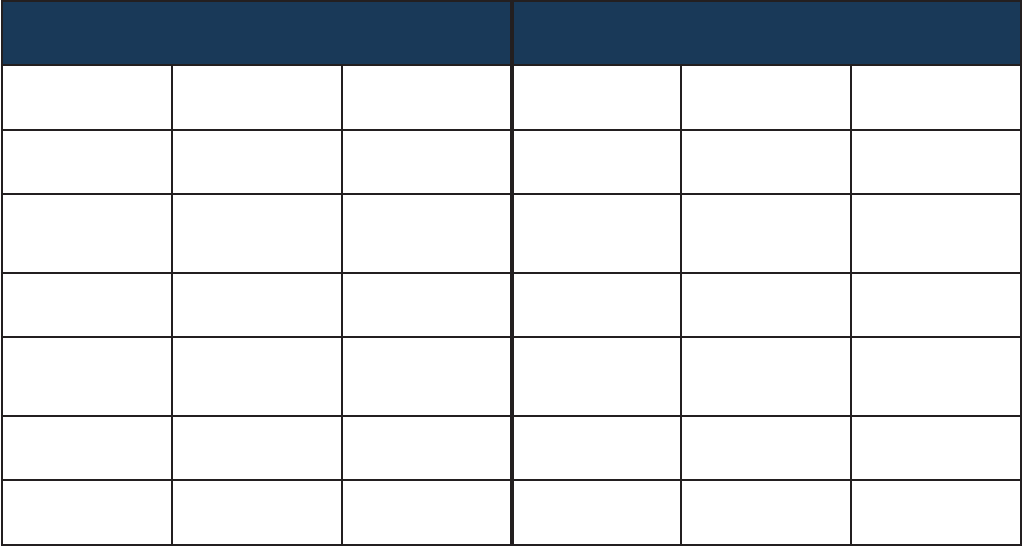

Exhibit 6: District policy regarding the conversion of tardies and/or early dismissals to

absences (n=102)

Source: OREA survey of attendance supervisors, December 2019.

Exhibit 7: How districts convert tardies/early dismissals to absences

Source: OREA surveys of attendance supervisors and principals, December 2019.

For districts and schools that permit

conversion absences, the conversion threshold

varies from three to ve tardies/early

dismissals or a prescribed number of minutes

(e.g., 420 minutes, or seven hours) to be

converted to one absence.

K

K

Typical school days run approximately seven hours, or 420 minutes, in accordance with the requirements outlined in SBE rule 0520-01-03-.02. Law and rule

require a minimum of 6.5 hours, but most districts extend the school day to seven hours.

Some districts use a prescribed number of minutes for

conversion absences.

“A student in school for less than 221 minutes, whether tardy

or early dismissals, would be counted as absent unexcused.”

Respondent to OREA survey of principals, Dec. 2019

28, 28%

44, 43%

30, 29%

Blanket policy for conversion absences

District does not allow conversion absences in any school

Principal discretion for conversion absences

Blanket policy for conversion absences

District does not allow conversion absences in any school

Principal discretion for conversion absences

35%

30%

13%

22%

64%

18%

6%

12%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

Only converts

unexcused

tardies/early dismissals

to unexcused absences

Excused tardies and/or

early dismissals

converted to excused

absences; unexcused

tardies/early dismissals

converted to

unexcused absences

All tardies/early

dismissals converted to

unexcused absences

Other

Principals (n=237) Attendance supervisors (n=33)

28%

43%

14

Exhibit 8: Number of tardies and/or early dismissals that equal an absence, according to

attendance supervisors and principals (n=266)

Note: is chart combines survey results from attendance supervisors and principals. e survey responses diered slightly between the two groups but may be

explained by factors relative to grade level, principal discretion, etc.

Source: OREA surveys of attendance supervisors and principals, December 2019.

In interviews and survey comments,

however, a few school ocials questioned

the legality of conversion absences, due in

part to the absence of any law regarding

this practice.

One concern raised by some attendance

supervisors and principals was whether

juvenile court judges would frown upon

a student being classied as truant based

in part on conversion absences. When

surveyed by OREA, juvenile court judges

were split nearly into thirds regarding this

practice, with most (39 percent) stating they

consider conversion absences on a case-by-

case basis.

One judge considers conversion absences

only for students who have already

accumulated ve unexcused absences,

none of which were based on conversion

absences. Another judge stated that if the

school uses conversion absences according

to the attendance policy sent to parents at

the beginning of the school year, then the

court accepts these absences. Other judges indicated they take conversion absences into consideration when

considering truancy cases, but they are not included in the actual truancy petition (i.e., they are considered

problems or early warning signs but not actually applied to the number of unexcused absences that bring the

case to court). Two judges commented that they do not interpret the law as allowing such absences to count in

truancy cases. (See more about truancy on page 31.)

Some school ocials expressed concern about the use of

conversion absences.

“We were under the impression that this was an illegal practice.”

Respondent to OREA survey of attendance supervisors, Dec. 2019

2

6

94

12

56

2

3

12

2

3

74

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 10 More

than 10

Other

12, 28%

14, 33%

17

, 39%

Yes No Case-by-case basis

Yes No Case-by-case basis

Source: OREA survey of juvenile court judges, February 2020.

Exhibit 9: Judges counting conversion absences in

truancy cases (n=43)

28%

15

Review of attendance data

School ocials, including attendance supervisors and principals, use attendance data to identify and analyze

student absenteeism problems, determine what intervention plans should be implemented, and evaluate

the eectiveness of the plans. TDOE recommends that districts review data regularly to identify trends in

student attendance.

On surveys distributed by OREA, principals and attendance supervisors were asked how frequently they

review attendance data in their school or district. e majority of respondents to both surveys review

attendance data at least weekly.

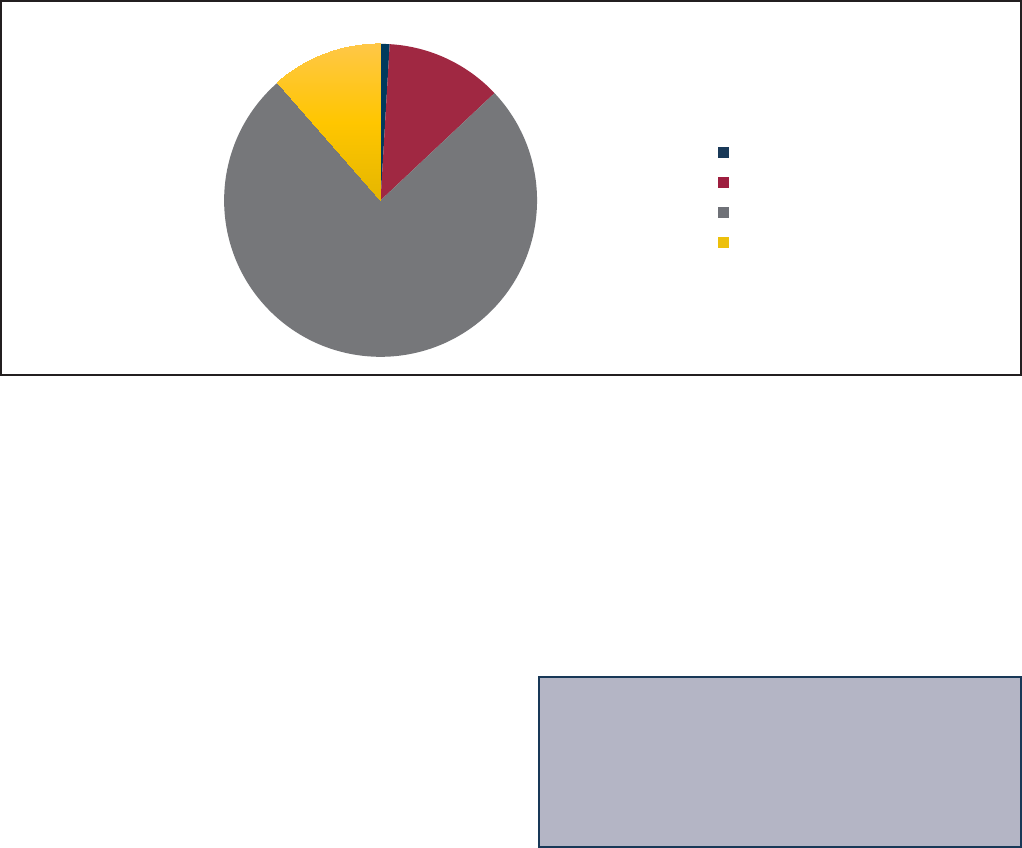

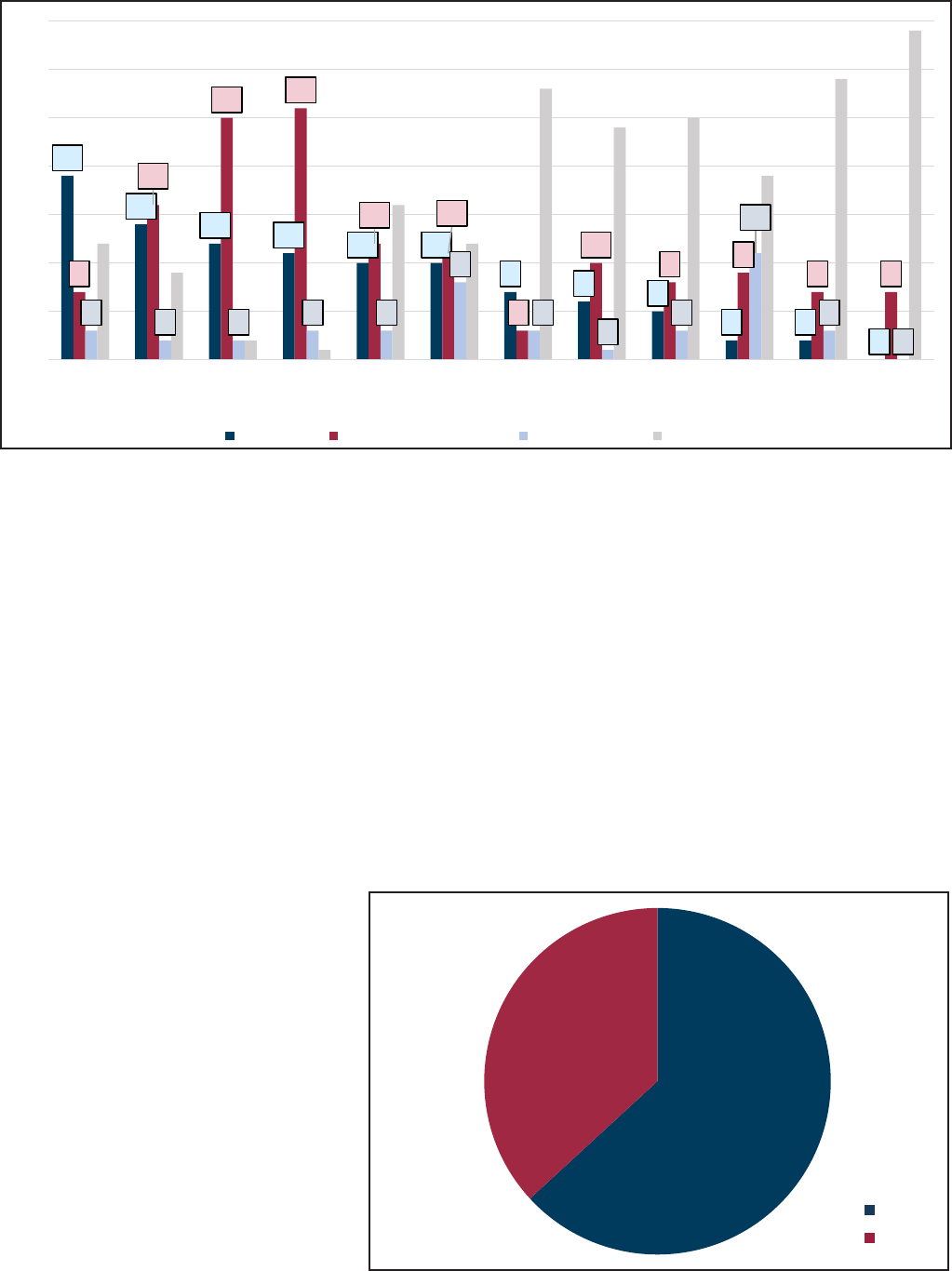

Exhibit 10: Frequency of attendance data review for attendance supervisors and principals

(n=584)

Note: is graph combines the attendance supervisor and principal survey results because the trends between the two surveys were consistent with one another.

Ninety-nine supervisors and 485 principals responded to this question.

Source: OREA surveys of attendance supervisors and principals, December 2019.

Districts must use one of ve vendors contracted by TDOE for managing their student data through a

student information system (SIS).

L

All vendors must provide consistent reporting on core data, but they also

oer districts optional data packages that allow for the tracking of specic attendance issues and data trends.

SIS packages vary by cost and function and can be customized to t a district’s specications and needs. An

SIS may, for example, autogenerate an attendance intervention once a student reaches a certain number of

unexcused absences or send a message to parents whenever their child misses class.

Data misreporting

e eectiveness of data review as a tool is dependent on data quality, however. Data misreporting can lead to

overlooked problem areas and missed opportunities for improvement.

M

Over the course of interviews with attendance supervisors and other district representatives, OREA

learned that in some districts over the past few years, student attendance data may have been misreported

unintentionally as a result of incorrect coding in the student information system, settings, or other issues.

Sixteen attendance supervisors (9 percent, each representing a dierent district) and 49 principals (16 percent)

indicated that data misreporting had occurred in their districts within the past four years. OREA did not

determine at what level (school, district, or state) the data misreporting took place.

L

ere are currently ve student information system (SIS) vendors contracted by TDOE as options for managing the student data of the state’s school districts:

Follett Schools Solutions (Aspen), Innite Campus, PowerSchool, Skyward, and Edupoint Educational Services (Synergy). All districts must use one of the state-

approved contracts, but they can choose state-hosting or vendor-hosting for their SIS packages.

M

e 2020 Accountability Protocol, the latest version of a document published annually by TDOE, describes how chronic absenteeism rates are calculated. e

2020 Accountability Data Appeals Guidance describes the appeals process and opportunities districts have to check and appeal their data.

150

246

128

33

12

7

8

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

Daily Weekly Monthly Quarterly Once a

semester

Yearly Data not

reviewed

16

Misreported data reduces the accuracy of attendance data and aects attendance-related accountability

measures. See page 30 for more information on these measures.

Exhibit 11: Data misreporting in last four years, according to attendance supervisors and

principals

Source: OREA surveys of attendance supervisors and principals, December 2019.

Data misreporting has also been an issue on the national level. e authors of the 2018 Data Matters report

from Attendance Works

N

note that data misreporting has been a problem since national chronic absenteeism

data was collected for the rst time by the federal Oce for Civil Rights during the 2013-14 school year. e

authors attributed problems with the consistency and accuracy of attendance data to the degree of variation

in attendance policies in school districts across the country, specically what counts and does not count as an

absence. e second time data on chronic absenteeism was collected from the nation’s school districts (during

the 2015-16 school year), Attendance Works found a greater awareness among districts of the data collection

protocols established by the federal Oce for Civil Rights, which likely led to better and more consistent

reporting. When data from 2013-14 was compared to the 2015-16 data, researchers found the number of

chronically absent students nationwide rose by roughly 790,000 students.

5

In some cases, schools that had reported no chronically absent students for the 2013-14 school year saw

a signicant increase in the number of such students for the 2015-16 school year. e report’s authors

hypothesized such changes were likely the result of improved data reporting. Turning back to Tennessee data

with this in mind, OREA identied 23 schools

O

that reported a chronic absenteeism rate of zero percent for at

least one of the three school years examined (2017, 2018, and 2019). For most of these schools, the chronic

absenteeism rate was zero for a single year; the rate for the other two years was not zero but was still well below

the state rate. Two schools reported no chronically absent students for two years and a rate below 1 percent

for the third year. One district had nine schools that reported a rate of zero percent in 2018, contributing

to the district’s reported rate of 0.7 percent that year. According to the district’s attendance supervisor, the

reported rates were incorrect, the result of a possible miscalculation issue. In another Tennessee district, data

misreporting was primarily responsible for a signicant drop in chronic absenteeism rates after the 2016-17

school year.

ree Tennessee districts with misreported data each explained that data miscoding in previous school years

had aected their rates, but in each case, the issues were caught and remedied with improved record keeping

practices, specied training for personnel, or increased eciency. Several school ocials told OREA in

interviews and surveys that to prevent future issues, they provided additional training for attendance clerks

and other individuals who work with data daily.

N

Attendance Works is a national nonprot agency whose mission is to advance student success and help close equity gaps by reducing chronic absenteeism.

O

is number includes only traditional schools, i.e., schools that are not virtual, adult, etc.

9%

59%

32%

16%

52%

32%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

Yes No I'm not sure.

Principals (n=545) Attendance supervisors (n=102)

17

Chronic absenteeism as a national focus

Chronic absenteeism is at the forefront of current national conversations about student attendance. Adopted

in 2015, the federal Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) requires all states to include chronic absenteeism

rates on their school report cards. Additionally, states are required to measure ve accountability indicators

annually. e rst four metrics are academic indicators: math and reading achievement, graduation rates for

secondary schools, English language prociency for English language learners, and an additional academic

indicator for postsecondary schools.

Each state must also choose at least one additional indicator for School Quality or Student Success (SQSS) to

measure on an annual basis. Tennessee, along with 35 other states (plus the District of Columbia and Puerto

Rico), has chosen to measure chronic absenteeism as an SQSS indicator. (Tennessee is one of nine states that

lists chronic absenteeism as its only SQSS indicator for all grade levels.) ESSA requires all states, even those

that have not chosen chronic absenteeism as their SQSS indicator, to report chronic absenteeism data to the

federal government and allows federal spending on training to reduce absenteeism. Since chronic absenteeism

was rst added to the state’s ESSA plan, TDOE has led training focused on chronic absenteeism in the form

of at least one major statewide conference, numerous presentations to attendance supervisors, and a series

of regional training events for school administrators. e department has also created chronic absenteeism

resources for districts, including FAQs, toolkits, additional resources for vulnerable student groups, and school

climate resources, which provide methods to assess reasons for chronic absenteeism in schools.

ESSA does not provide a standard denition of chronic absenteeism, allowing states to set their own

parameters for the measure. Of the 36 states that chose chronic absenteeism as the SQSS in their ESSA plan,

27 states, including Tennessee, dene chronic absenteeism as missing 10 percent or more of instructional

days over the course of the school year.

6

is is the most common denition of chronic absenteeism, used by

Attendance Works as its working denition of the term. Research suggests that missing 10 percent or more

of instructional days may put students in danger of academic and social consequences. In Tennessee, districts

operate on a 180-day academic calendar, so a student who is enrolled for the entire school year becomes

chronically absent once he or she accrues 18 absences.

7

Some states use other denitions for chronic absenteeism, as shown in Exhibit 12.

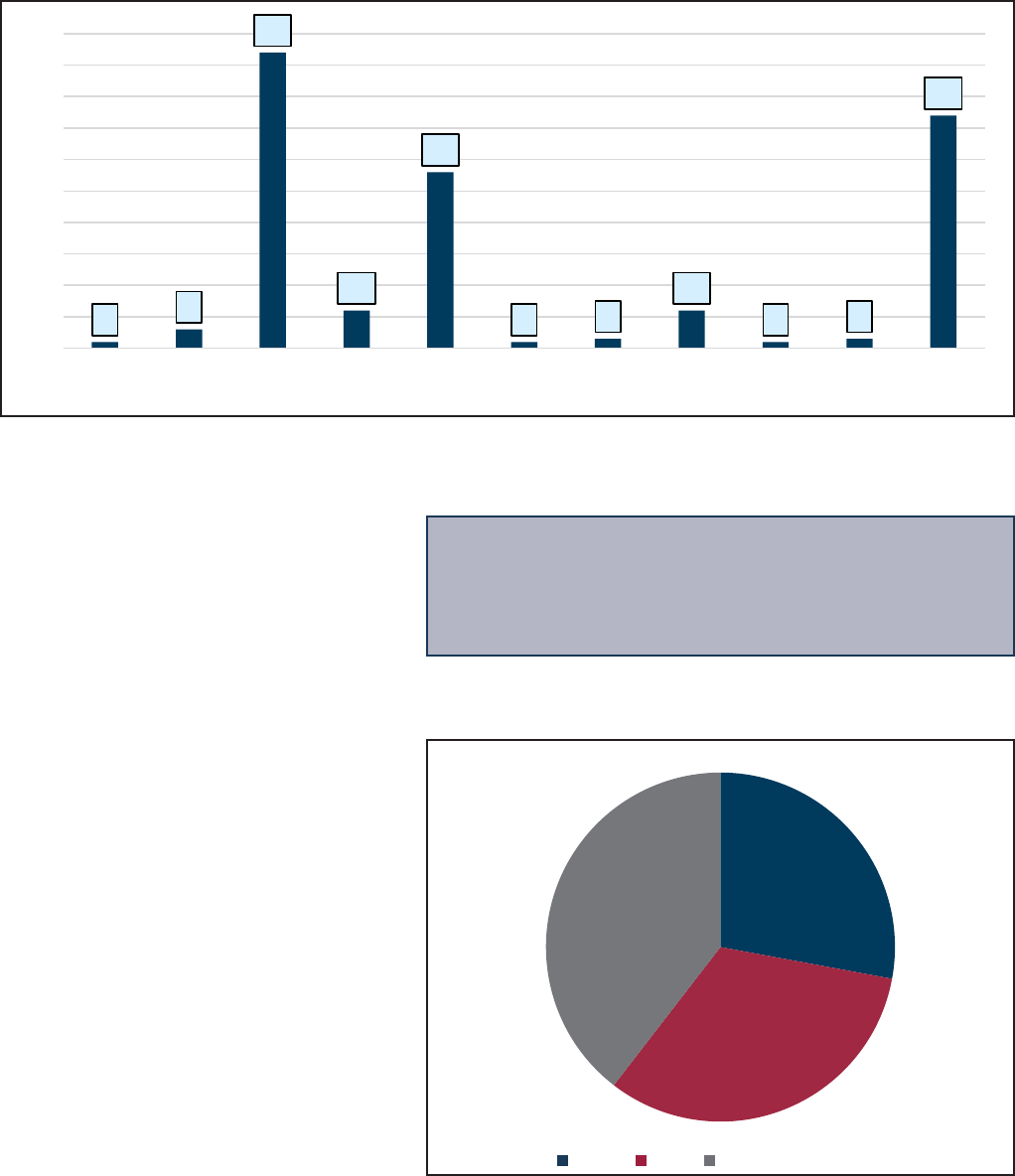

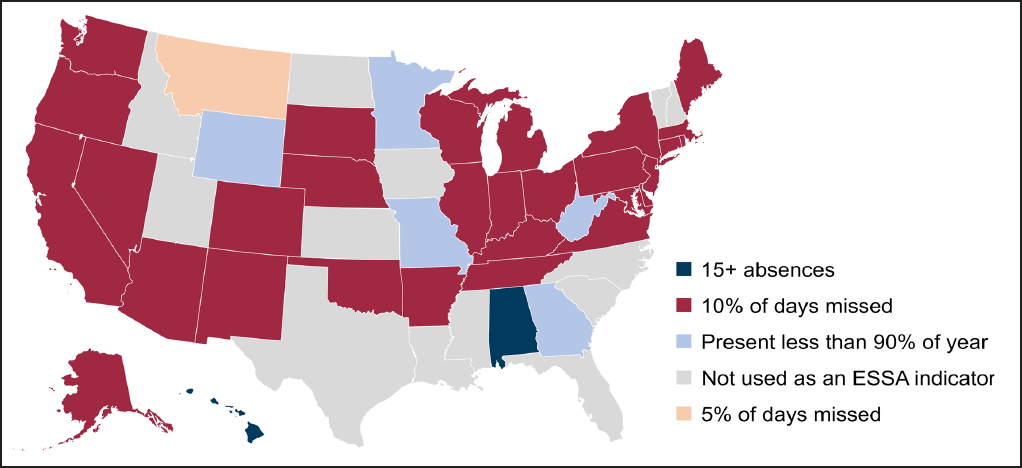

Exhibit 12: Chronic absenteeism measures used in states’ ESSA Plans

Source: FutureEd, 2017.

18

Measuring chronic absenteeism in Tennessee

In Tennessee, the chronic absenteeism rate is measured based on a student’s total number of days enrolled in

a district.

P

If the chronically absent student is enrolled in a district for at least half of the instructional days in

the school year, he or she is counted in the district’s chronic absenteeism rates. e same threshold is used to

calculate school-level chronic absenteeism rates.

Q

If a chronically absent student is not enrolled in any district

for at least half of the school year but is enrolled in a public school or schools in the state for at least 45

instructional days, the student’s chronic absenteeism is factored into the state rate but not that of any district.

ough TDOE started collecting chronic absenteeism data around 2013, chronic absenteeism rates were rst

included on the State Report Card in 2018. Between the 2017 and 2019 school years, Tennessee’s overall

chronic absenteeism rate dropped by 3.71 percent, a dierence of nearly 5,000 students, while total enrollment

increased by just over 1,300 students (an increase of 0.14 percent). In 2017, there were 134,675 chronically

absent students in Tennessee, accounting for 13.6 percent of the total K-12 student population. e statewide

rate of chronic absenteeism decreased slightly to 13.3 percent in 2018 and to 13.1 percent in 2019.

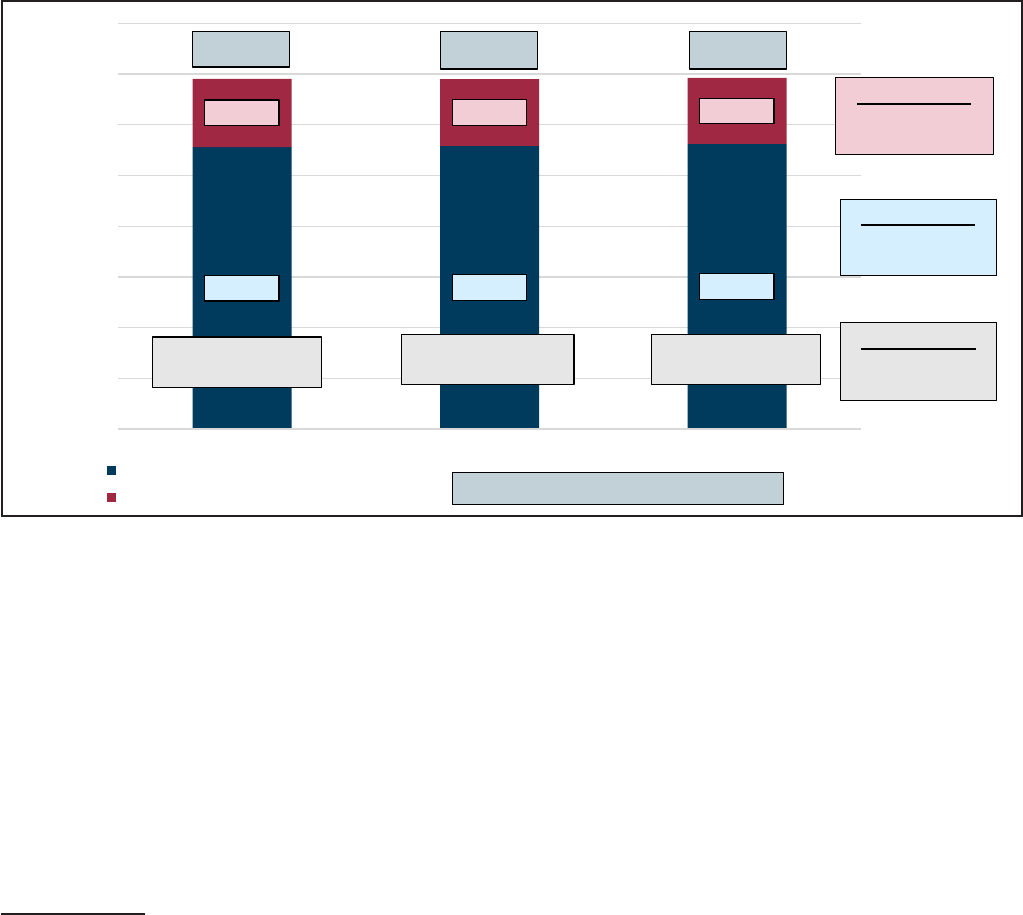

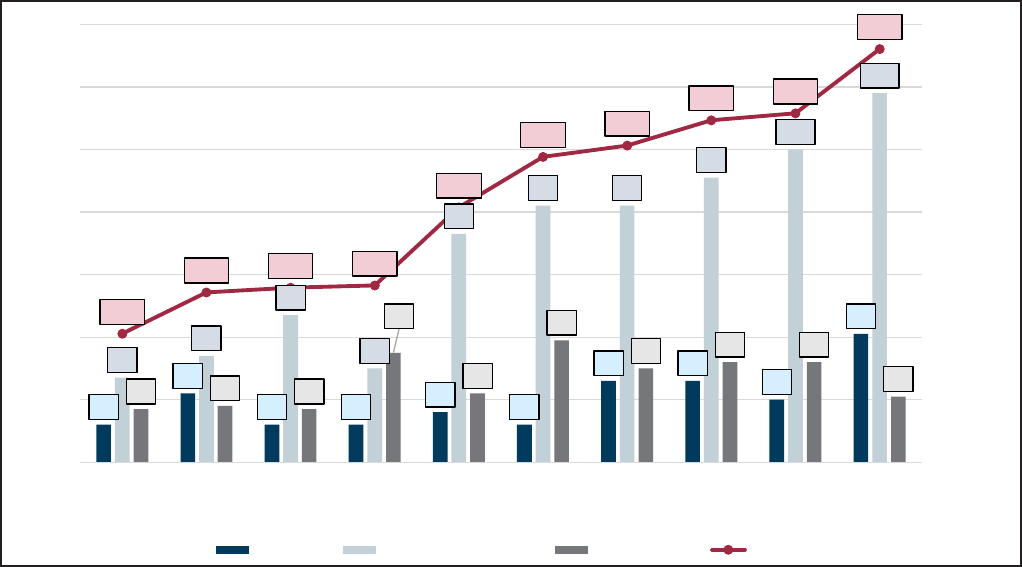

Exhibit 13: Chronic absenteeism in Tennessee | 2017 through 2019

Note: is analysis was done using publicly available suppressed state-level data. Enrollment numbers include students who may not have been enrolled in a district

long enough to be counted in district-level chronic absenteeism data.

Source: OREA analysis of TDOE data.

In 2019, nearly 70 percent of Tennessee school districts posted chronic absenteeism rates that were at or below

the state rate of 13.1 percent. Forty-four percent of the remaining districts were within 2 percentage points of

the state rate.

P

All research, including survey data, reects procedures and policies in place prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Q

Note: Students who are enrolled in two schools or districts for exactly 50 percent of the school year will count for both schools and both districts for accountability purposes.

856,060

858,442

862,421

134,675

131,717

129,676

300,000

400,000

500,000

600,000

700,000

800,000

900,000

1,000,000

1,100,000

2016-17 2017-18 2018-19

Students not chronically absent

Students chronically absent

13.6%

13.3%

13.1%

Total enrollment:

990,159

Total enrollment:

992,097

Total enrollment:

990,735

Statewide rate of chronic absenteeism

Total change:

-3.71%

-4,999 students

Total change:

+0.74%

+6,361 students

Total change:

+0.14%

+1,362 students

19

Exhibit 14: Chronic absenteeism in Tennessee districts | 2018-19

Source: OREA analysis of TDOE data.

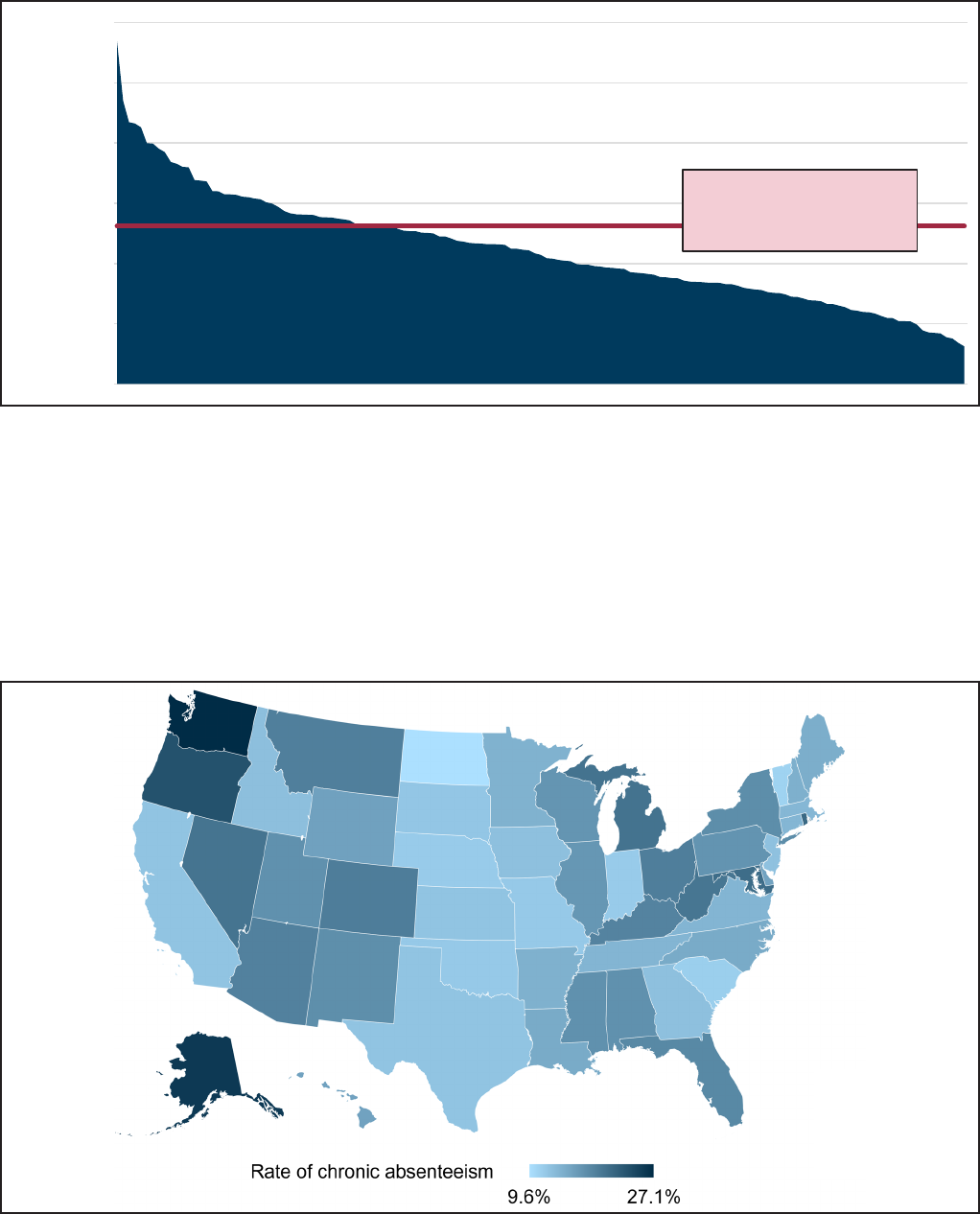

In 2015-16, the last time national chronic absenteeism data was collected and reported by the federal Oce

for Civil Rights (OCR), Tennessee’s chronic absenteeism rate of 13.8 percent ranked 18th lowest of all states

and fell below the nationwide average of 15.9 percent. e OCR dened a chronically absent student as one

who missed 15 or more days from school, a stricter threshold than the denition currently used by most states

(including Tennessee), i.e., 10 percent or more days in the instructional school year. at year Washington had

the highest rate at 27.1 percent, while North Dakota’s rate of 9.6 percent was the lowest.

Exhibit 15: Chronic absenteeism by state | 2015-16

Note: ese rates are based on dening chronic absenteeism as missing 15 days of school. e denition of chronic absenteeism used by Tennessee is missing at least

10 percent of instructional days (typically 18 days).

Source: U.S. Department of Education, Oce for Civil Rights.

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

Chronic absenteeism rate

Statewide rate of

chronic absenteeism:

13.1%

20

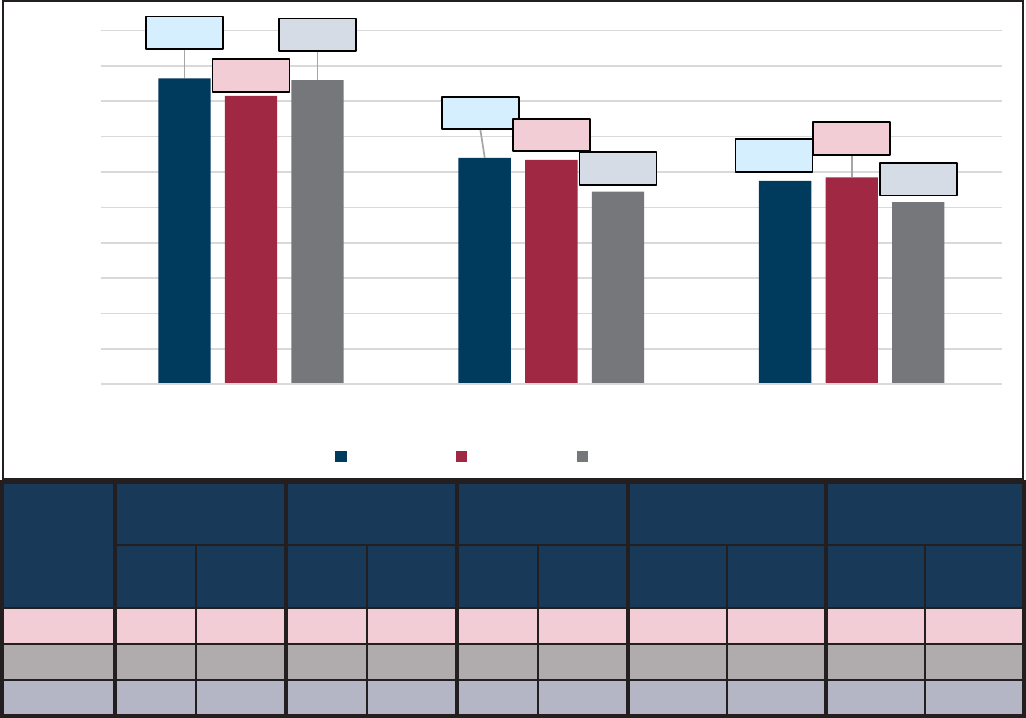

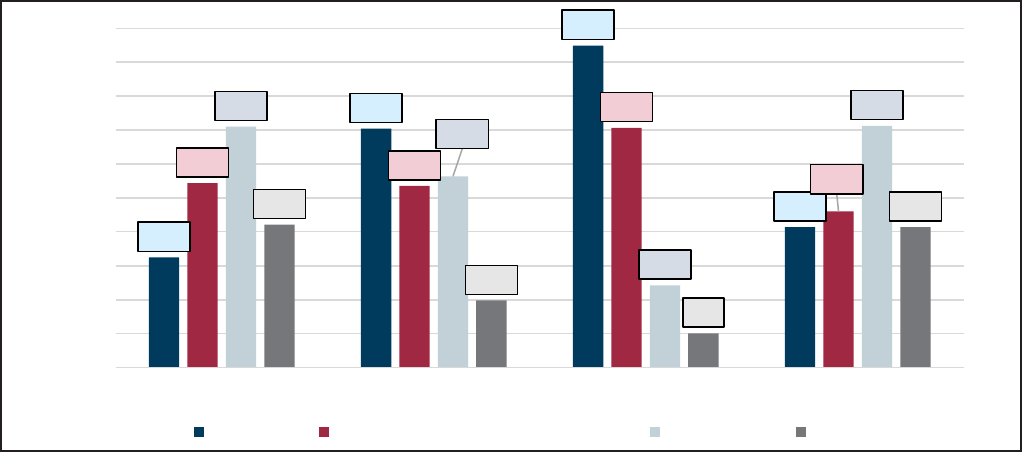

Chronic absenteeism by student group

Economically disadvantaged students

Between the 2017 and 2019 school years, the percentage of economically disadvantaged students who were

chronically absent was 20.9, as compared to 9.3 percent of students not economically disadvantaged. While

just over one-third of Tennessee students were economically disadvantaged, just over half (55 percent) of

chronically absent students were economically disadvantaged based on a three-year average.

In 2018, the national nonprot Attendance Works

released a report that analyzed nationwide attendance

data collected by the OCR. e report showed that

schools with the highest rates of poverty tend to have

higher levels of chronic absenteeism.

R,8

Ninety-seven principals (20 percent) who responded

to the OREA survey indicated that economically

disadvantaged students in their schools may have

transportation issues that prevent them from coming to

school on a regular basis. Many principals cited parent/

student apathy toward education as an issue for some

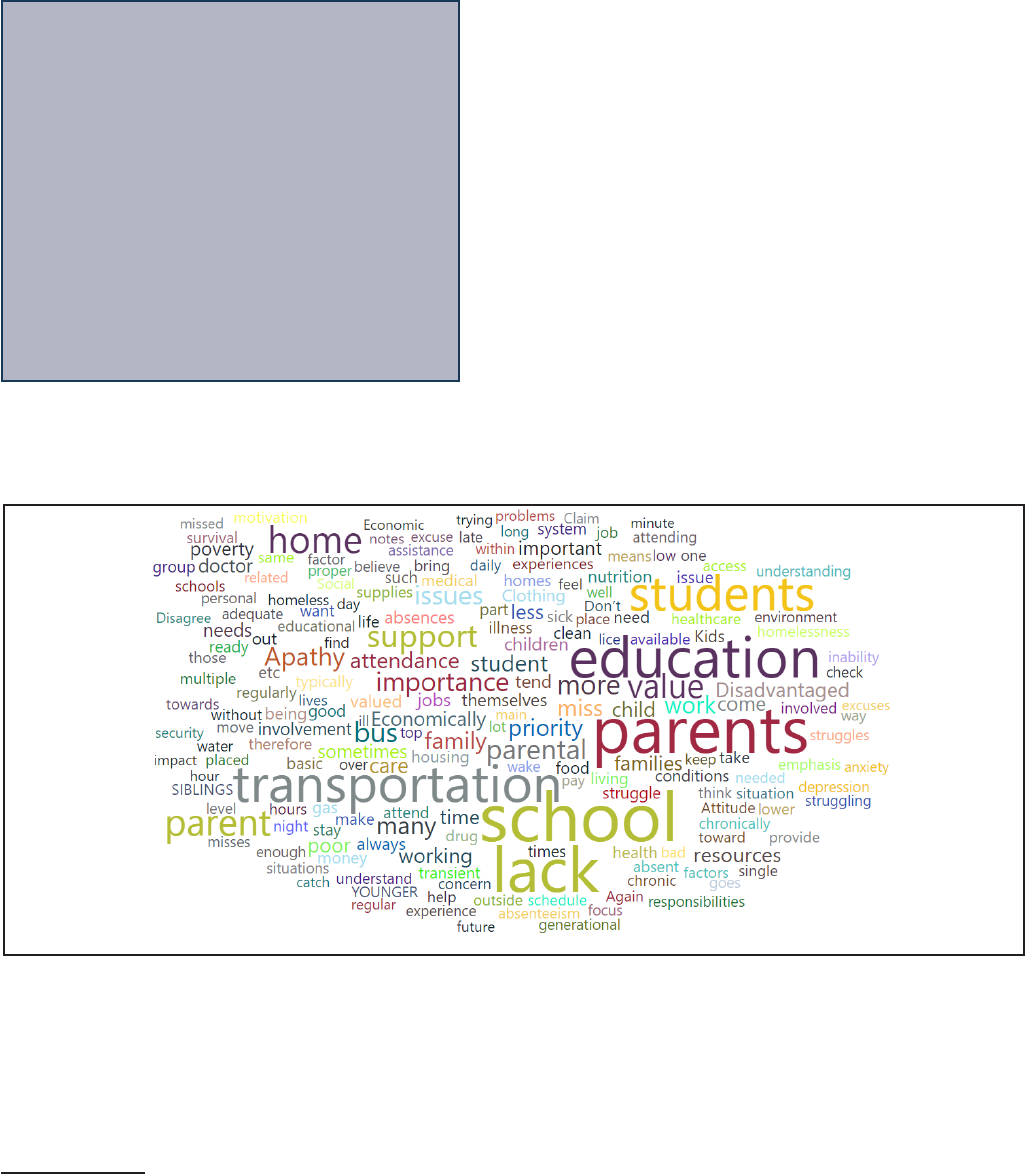

economically disadvantaged students. Other barriers

mentioned by principals included lack of access to

healthcare, poor nutrition, and lack of basic resources like housing, clothing, and more.

Exhibit 16: Perceived reasons for the high chronic absenteeism of economically

disadvantaged students, according to principals

Source: OREA survey of principals, December 2019.

Free and reduced-price meals

Students who are economically disadvantaged may lack access to basic needs, including food. Children who

do not have enough to eat are more likely to develop and struggle with behavioral, emotional, mental, and

academic problems. Such children are also more likely to be absent or tardy. Free and reduced-price meals at

school may encourage student attendance for some students.

R

OCR data is based on missing 15 days of school, while Tennessee denes chronic absenteeism as missing 10 percent or more of instructional days (typically 18 days).

Economically Disadvantaged

Students in Tennessee

Tennessee denes economically disadvantaged

students (or “at risk” students) as those who are

directly certied for specic state and federal

assistance programs, and those who are

identied as homeless, migrants, or runaways

as well as students in foster care.

Students who are directly certied are

those whose families are participating in the

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

(SNAP), Temporary Assistance for Needy

Families (TANF) program, or Head Start.

21

Free and reduced-price breakfast may be oered by schools in addition to lunch. Sixty percent of attendance

supervisors (59 respondents) and 49 percent of principals (226 respondents) responding to OREA surveys

reported that their students have access to free breakfast at their schools. Approximately 65 percent of

Tennessee students who qualify for free or reduced-price lunches also eat breakfast at school, ranking the state

above the national average of 57 percent. On average, students who eat school breakfast attend 1.5 more days

of school and are more likely to graduate high school than their peers who do not eat breakfast.

In most schools, breakfast is oered before the school day begins and students must arrive early to participate.

To increase student participation in school breakfast programs, the coordinated school health department at

TDOE encourages schools to institute alternative breakfast models such as Breakfast in the Classroom (served

in the classroom as the school day begins), Second Chance breakfast (served after rst period in either the

cafeteria or mobile classes throughout the school), or Grab and Go breakfast (served at easy to access locations

and eaten in the classroom). TDOE reports that the average participation rate for school breakfast programs

in Tennessee goes up to 90 percent when an alternative breakfast model is used.

On the OREA surveys, 45 percent of attendance supervisors (45 respondents) and 28 percent of principals

(130 respondents) indicated alternative breakfast models are used in their districts and schools.

Family resource centers

Family resource centers (FRCs) are often used as tools to address student absenteeism and target many of

the factors that commonly aect economically disadvantaged students. FRCs provide or assist students

and families with obtaining essential goods and services, such as food, clothing, and housing. e centers,

operating in 79 school districts within 65 counties, may be run directly by the district or in partnership with

another organization.

9

All centers are to collaborate with other state and local agencies, churches, and/or

nonprots to help students and their families meet a variety of needs.

Each FRC identies focus areas and sets specic goals based on the needs of the students and families in

the school district. As of November 2020, 51 of the state’s 102 FRCs had identied student attendance and

truancy as a primary focus. Over half of attendance supervisors (55 respondents, each representing dierent

districts) and 31 percent of principals (143 respondents) indicated on the OREA surveys that they have used

their FRC for help with issues that aect student attendance, such as by securing transportation for students,

meeting family health needs such as chronic lice infestation, and assisting with hotel arrangements for families

who need housing.

Reduced public assistance

A Tennessee Department of Human Services (DHS) rule requires school attendance, including kindergarten,

of all school-age children who receive need-based public assistance through the state’s Families First program,

unless good cause is established for nonattendance.

10

Parents of school-age children must provide verication

of school enrollment (e.g., enrollment documents, a copy of the child’s most recent report card).

S

e

maximum penalty for failure to comply with the school attendance requirement is a 20 percent reduction

in public assistance benets. is penalty is to be assessed whenever verication of school attendance is not

provided and/or a child is found truant without a good cause for missing school.

Data provided by DHS in July of 2020 show that the benets for approximately 1,000 families were reduced

in 2018 and 2019 because they did not meet the student attendance requirements.

S

If parents choose to homeschool, they are not exempt from the Families First Employment and Training participation requirement (i.e., participating in the TANF

workforce development and employment program).

22

Exhibit 17: Reduced DHS public assistance for school attendance | 2015 through 2020 (partial)

Source: Department of Human Services.

An individual under the age of 20 without a high school diploma who is the head of a household and has a

child who is at least 16 weeks of age must work toward attaining a high school diploma or its equivalent or

risk a 20 percent reduction in public assistance benets.

11

Students with disabilities

From 2017 to 2019, students with disabilities were 1.45 times more likely to be chronically absent than

students without disabilities (18.3 percent vs. 12.6 percent). is was on par with OCR attendance data

from the 2015-16 school year, which showed that students with disabilities were 1.5 times more likely to be

chronically absent than students without disabilities.

T,12

Students with disabilities made up 13 percent of the

total student population in the state and nearly 18 percent of all chronically absent students from 2017 to 2019.

Respondents to the OREA survey of principals indicated students with disabilities face additional barriers to

attendance because of physical or mental limitations that make a typical school day dicult to navigate.

U

Over

a third of principals stated that students with disabilities tend to miss more school because of chronic health

issues and frequent doctor’s appointments. A few principals mentioned that some students with disabilities

may experience school-related anxiety that can aect their attendance.

T

OCR data is based on missing 15 days of school, while Tennessee denes chronic absenteeism as missing 10 percent or more of instructional days (typically 18

days).

U

Students with disabilities may have a modied attendance schedule in their IEP or modied 504 plan if they are unable to follow the typical school schedule. (See

pages 45-47 for more information.)

2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

January

297 74 62 59 103 130

February

33 73 72 83 62 76

March

52 96 71 65 83 100

April

48 75 65 78 102 59

May

53 80 60 57 81 29

June

67 74 62 84 90 17

July

47 45 57 77 109 –

August

26 58 69 121 118 –

September

47 106 60 126 104 –

October

73 64 86 141 116 –

November

156 99 69 106 108 –

December

86 97 79 82 83 –

Total 985 941 812 1,079 1,159 –

23

Exhibit 18: Perceived reasons for the high chronic absenteeism of students with disabilities,

according to principals

Source: OREA survey of principals, December 2019.

English learners

e student group that was the least chronically absent from 2017 through 2019 was English learners, who were

nearly 1.45 times less likely to be chronically absent than students who were not English learners (9.4 percent

vs. 13.6 percent). is is consistent with the national attendance trends for students who are English learners.

According to national data collected by the OCR, English learners are approximately 1.2 times less likely to be

chronically absent than their non-English learner peers.

V,13

When asked about this trend on the OREA survey,

many principals stated that the families of English learner students place a high value on education because of

the opportunities it aords them in America. Other principals cited a generally strong work ethic in the English

learner population in their schools and an eagerness to assimilate into the local culture.

Exhibit 19: Perceived reasons for the low chronic absenteeism of English learners, according

to principals

Source: OREA survey of principals, December 2019.

V

OCR data is based on missing 15 days of school, while Tennessee denes chronic absenteeism as missing 10 percent or more of instructional days (typically 18 percent).

24

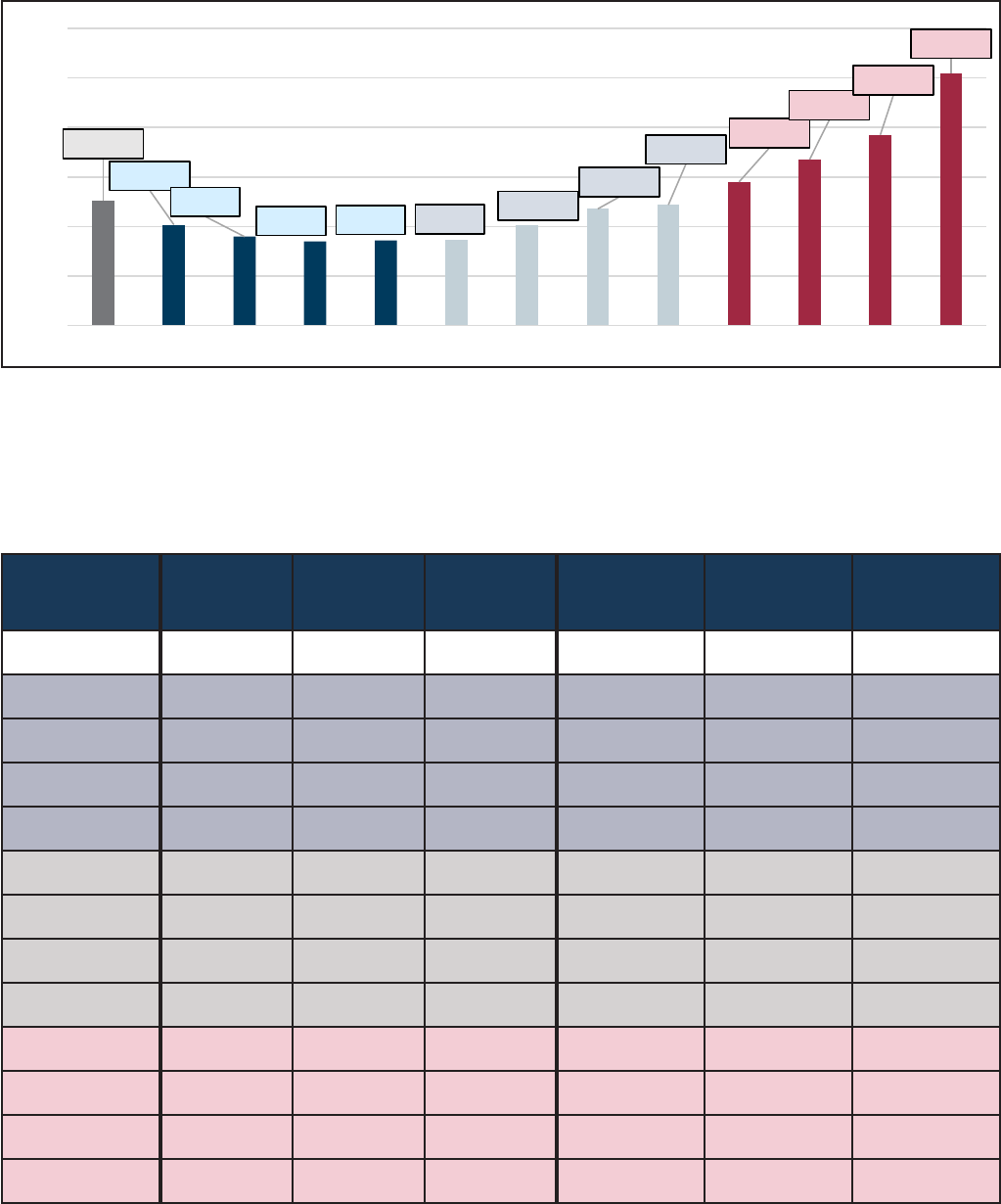

Racial groups

Black students had higher chronic absenteeism rates than either White or Hispanic students for 2017 through

2019. Analysis of students by race showed that the number of chronically absent Black students decreased by

over 1,300 students from 2017 to 2019, however. But since the total population of Black students decreased by a

greater amount over the time period, the chronic absenteeism rate for Black students stayed relatively the same.

In spite of a population increase of over 9,300 students, the number of Hispanic chronically absent students

decreased by just over 180, which resulted in a net decrease of chronic absenteeism for Hispanic students over

the time period.

e chronic absenteeism rate for White students decreased by nearly 15 percent during the time period, as the

number of those who were chronically absent declined by over 15,000 at the same time the total population of

such students decreased by almost 30,000.

Exhibit 20: Chronic absenteeism (CA) rate of Black, White, and Hispanic students | 2017

through 2019

Note: Data for Black and Hispanic students is used in measures by TDOE along with Native American students (not shown here).

Source: OREA analysis of TDOE data.

Attendance data for Black and Hispanic students is used in accountability measures by TDOE along with

data for Native American students (not shown in the Exhibit 20). When the data for these student subgroups

is broken down further, as shown in Exhibit 21, Black students and Native American students had chronic

absenteeism rates above the statewide rate for the three years reviewed. All other groups were below the

statewide rate for chronic absenteeism.

17.3%

12.8%

11.5%

16.3%

12.7%

11.7%

17.2%

10.9%

10.3%

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

14%

16%

18%

20%

Black White Hispanic

Rate of chronic absenteeism

2016-17 2017-18 2018-19

2016-17 2017-18 2018-19

Change in CA

students

Change in all

students

CA Total CA Total CA Total

Number

change

Percent

change

Number

change

Percent

change

Black

41,093 237,946 38,687 237,892 39,781 231,423 -1,312 -3.19% -6,523 -2.74%

White

80,521 627,192 79,198 621,207 64,967 597,244 -15,554 -19.05% -29,948 -4.77%

Hispanic

11,210 97,298 11,924 101,718 11,028 106,633 -182 -1.62% +9,335 +8.75%

25

Exhibit 21: Chronic absenteeism by race | 2017 through 2019

Source: OREA analysis of TDOE data.

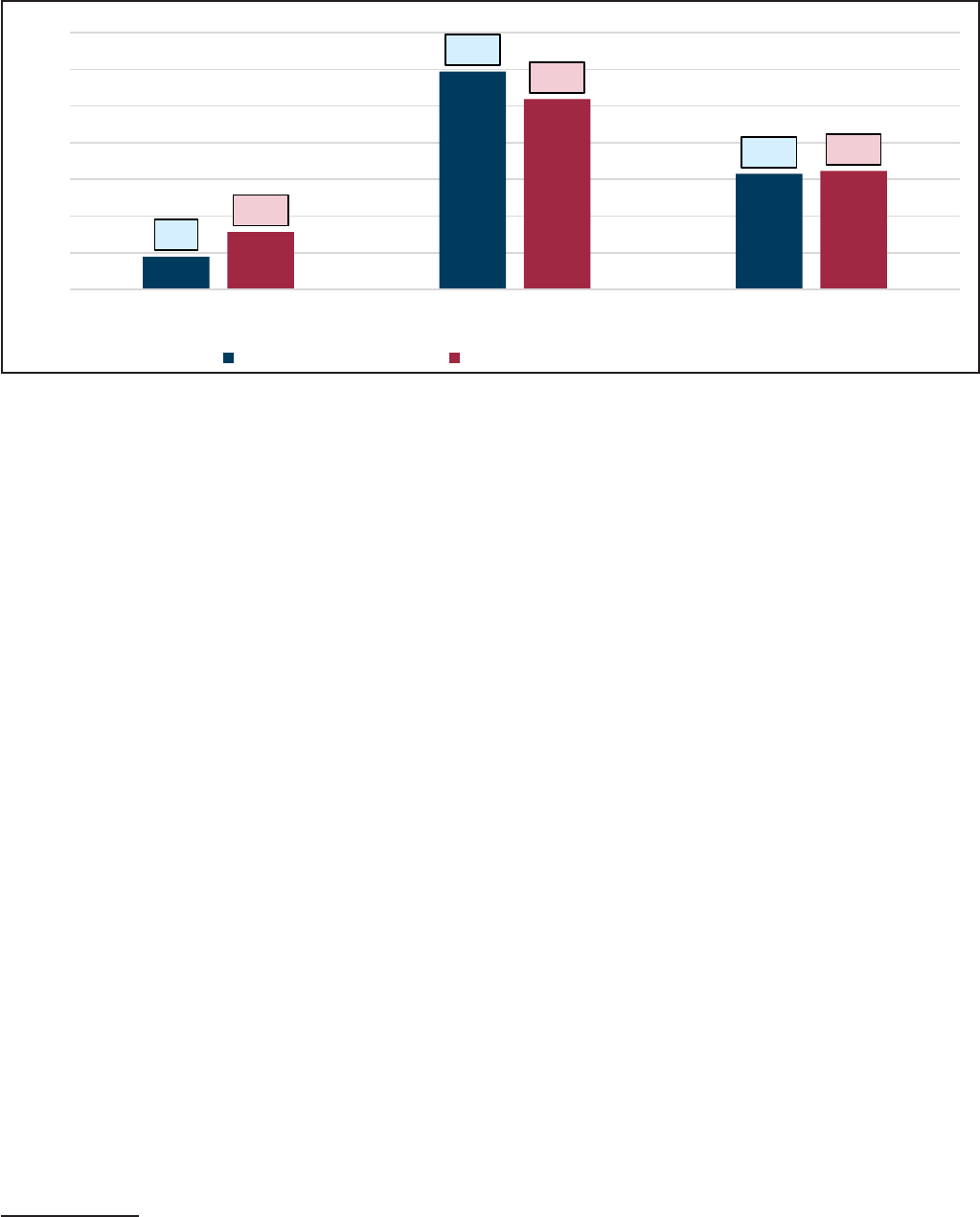

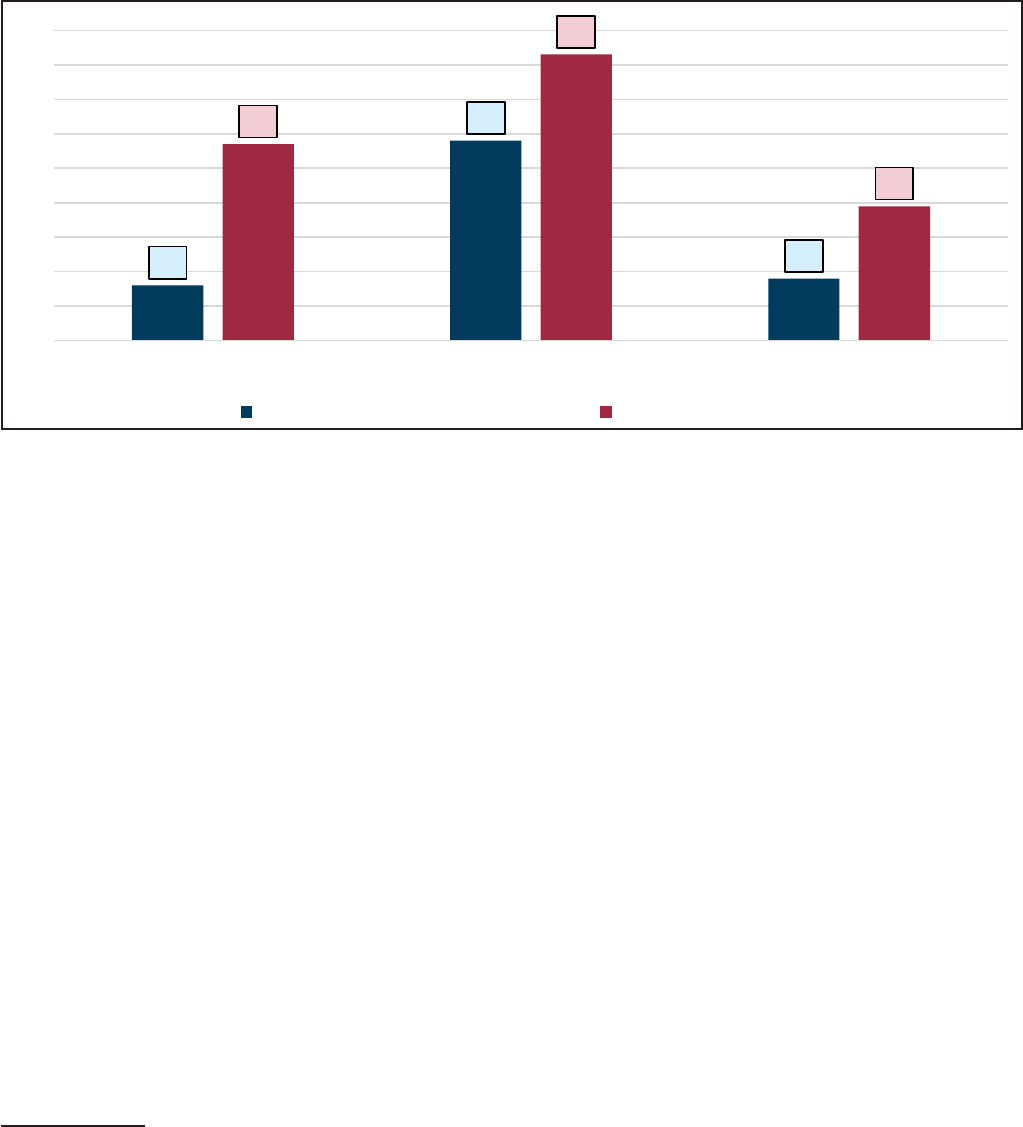

Between 2017 and 2019, English learners was the only student subgroup with a chronic absenteeism rate

below the state rate of 13.3 percent. e chronic absenteeism rates of economically disadvantaged students,

students with disabilities, and Black or Hispanic students were all above that of the state.

W

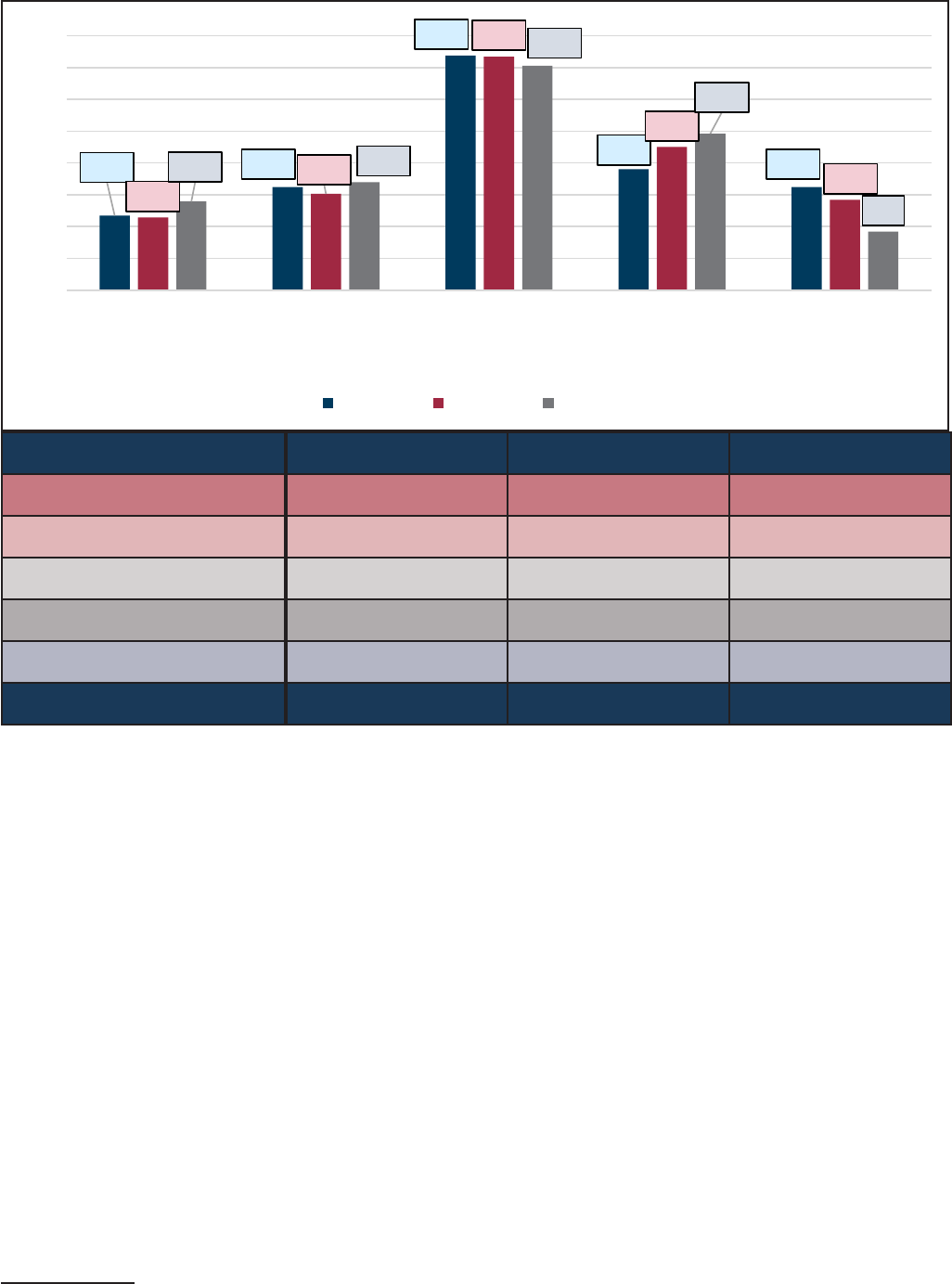

Exhibit 22: Chronic absenteeism of student subgroups | 2017 through 2019

Note: Black and Hispanic students are used in measures by TDOE along with Native American students (not shown here).

Source: OREA analysis of TDOE data.

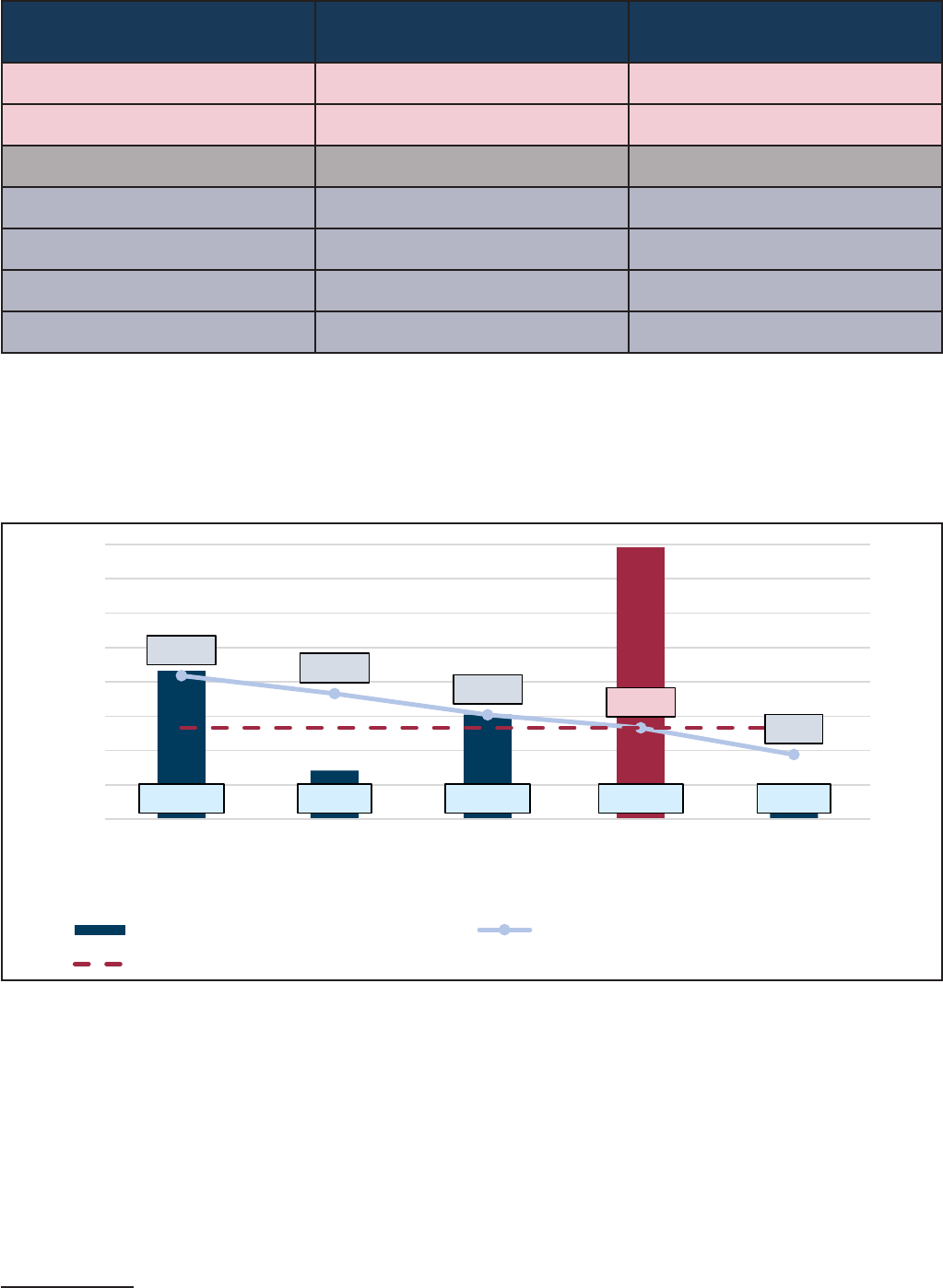

Grade levels

In Tennessee, the four high school grades had the highest rates of chronic absenteeism in 2017, 2018, and

2019, followed closely by kindergarten and 8th grade. Chronic absenteeism rates for students in grades 2

through 5 stayed under 10 percent for all three years; the lowest rates of chronic absenteeism were found

in grades 3 through 5. e rate steadily increased through middle school and, more rapidly, in high school.

Chronic absenteeism rates for 9th through 12th grade students were above the state rate for each of the three

years examined. On average, seniors were 67 percent more likely to be chronically absent than 3rd graders,

who were the least likely to be chronically absent.

W

See Appendix C for a more detailed breakdown of the chronic absenteeism of student subgroups.

Average number of CA

students per year

Percent CA

Black

39,854 16.9%

Native American

535 15.4%

State Rate 132,023 13.3%

White

74,895 12.2%

Hispanic

11,387 11.2%

Hawaiian or Pacic Islander

189 10.1%

Asian

1,064 4.6%

216,205 70,650 152,273 396,068 17,452

20.9%

18.3%

15.2%

13.3%

9.4%

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

40%

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

350,000

400,000

Economically

disadvantaged

(n=1,034,976)

Students with

disabilities

(n=385,228)

Black/Hispanic

students

(n=1,012,910)

All students

(n=2,972,991)

English learners

(n=185,963)

Number of chronically absent students Percent chronically absent

State rate

26

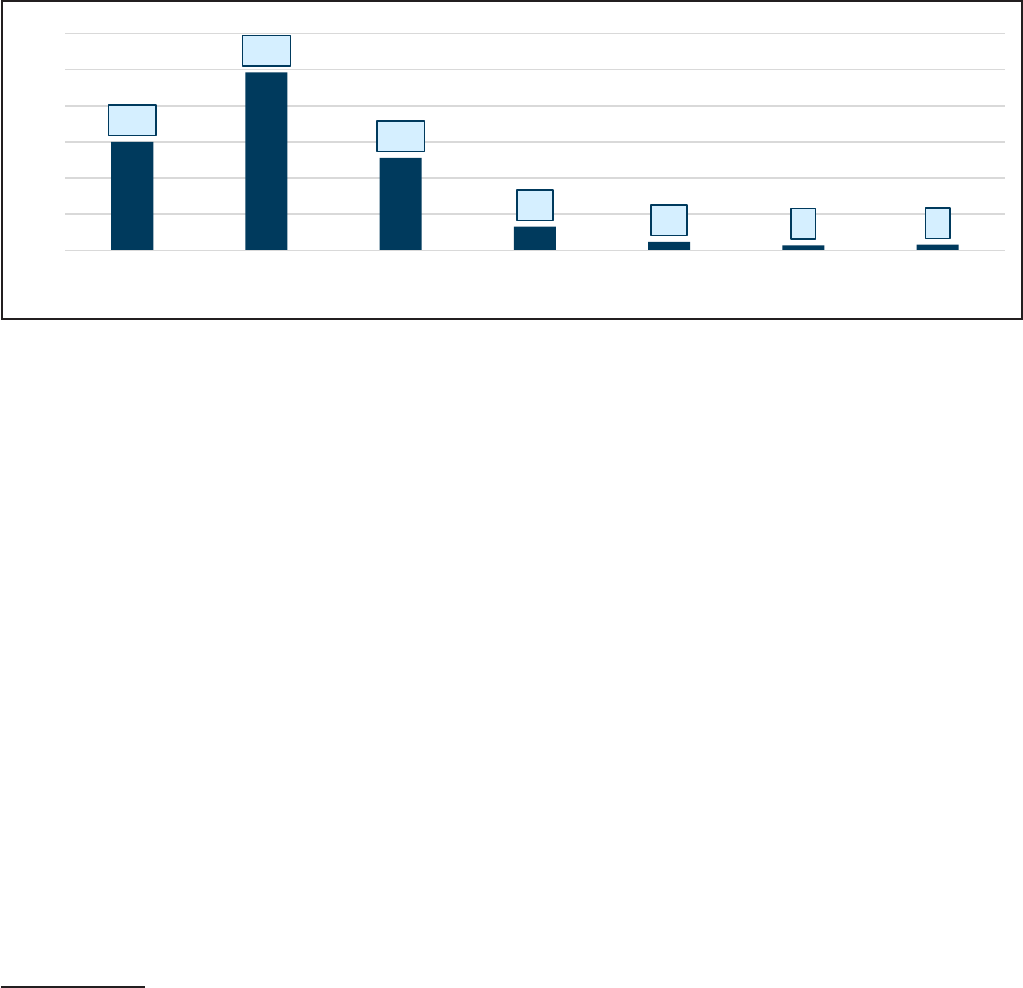

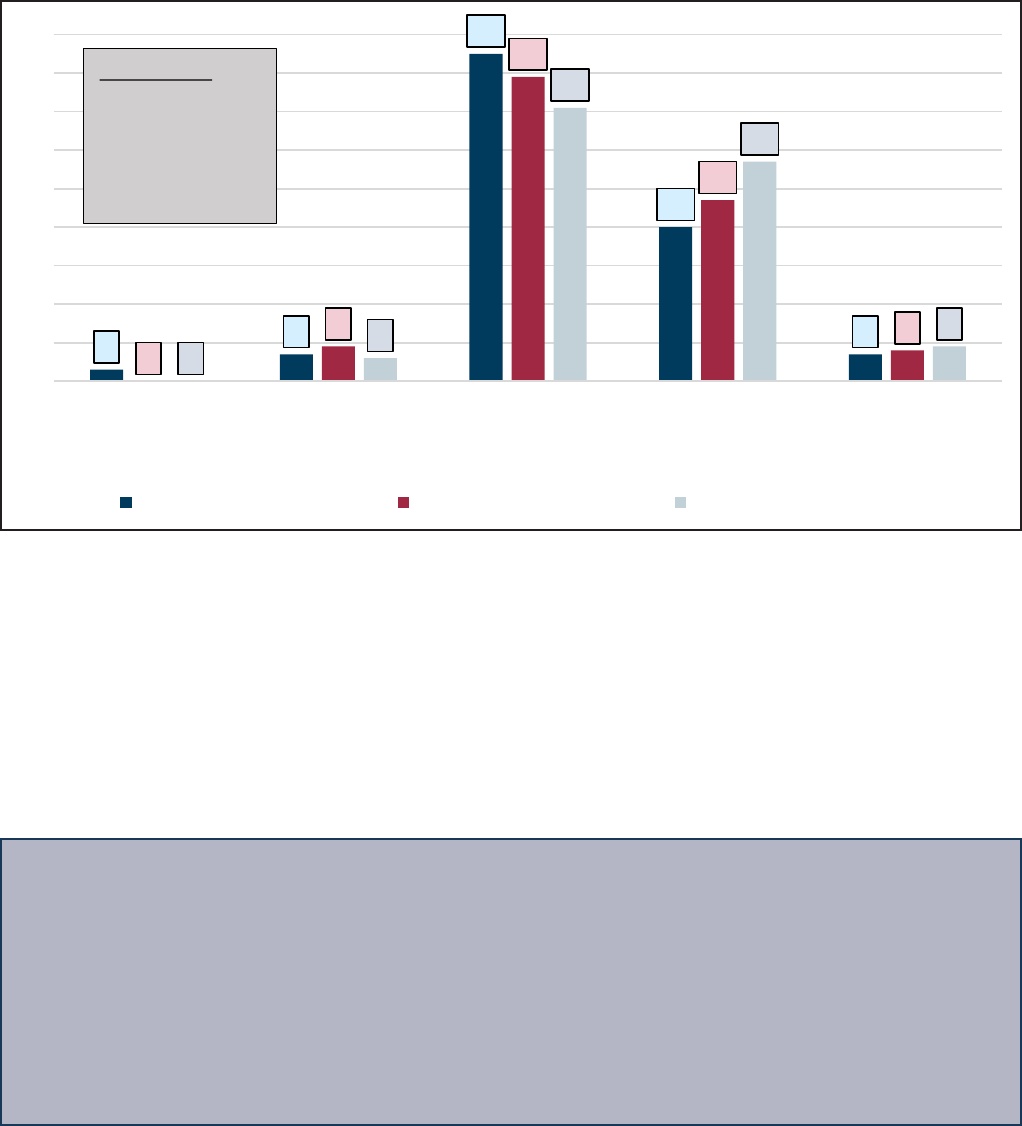

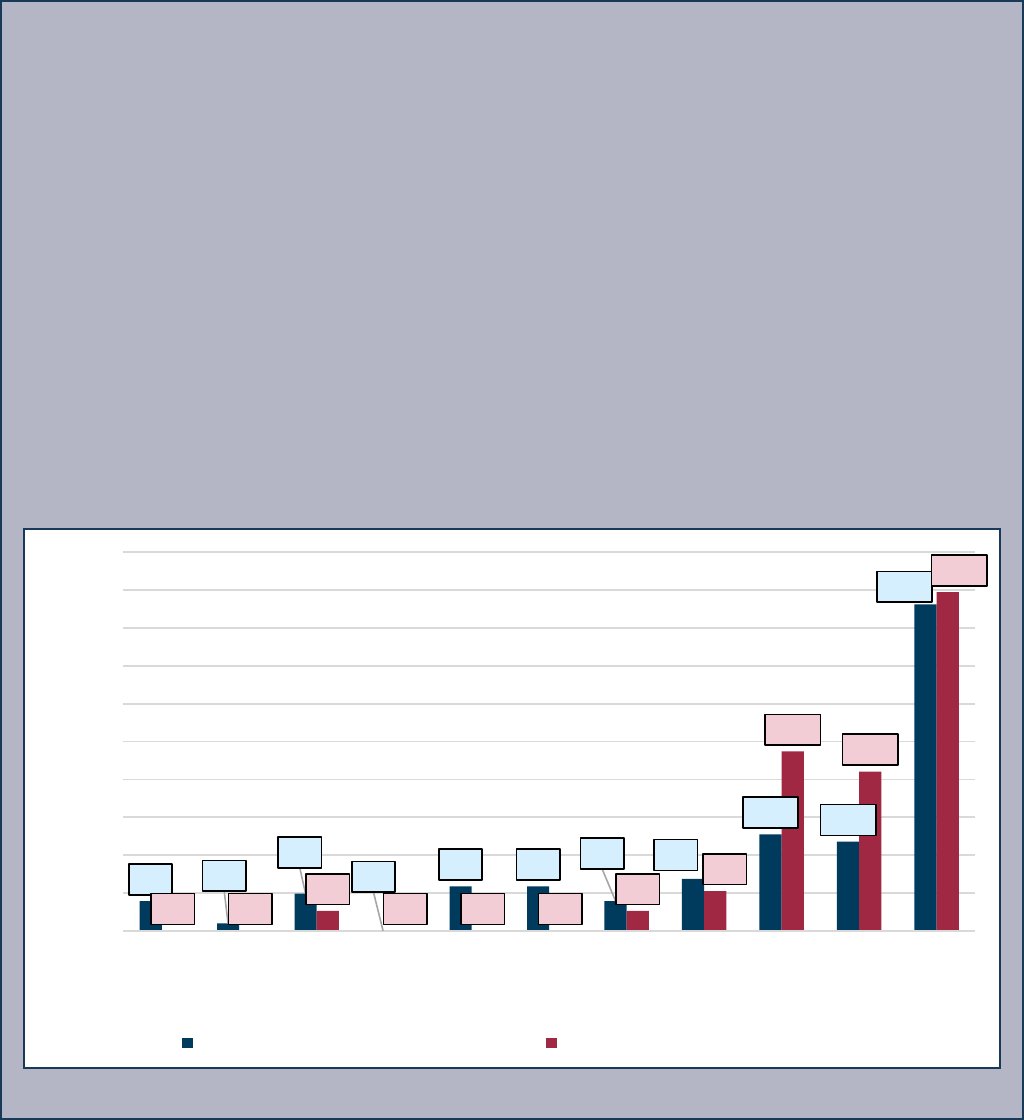

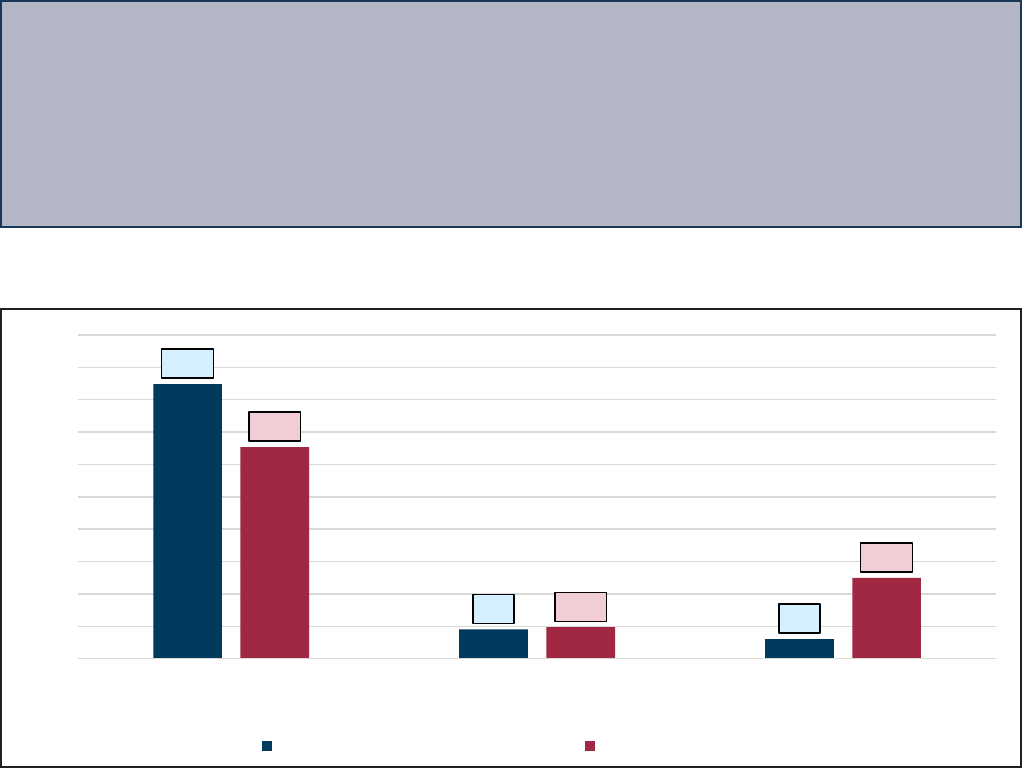

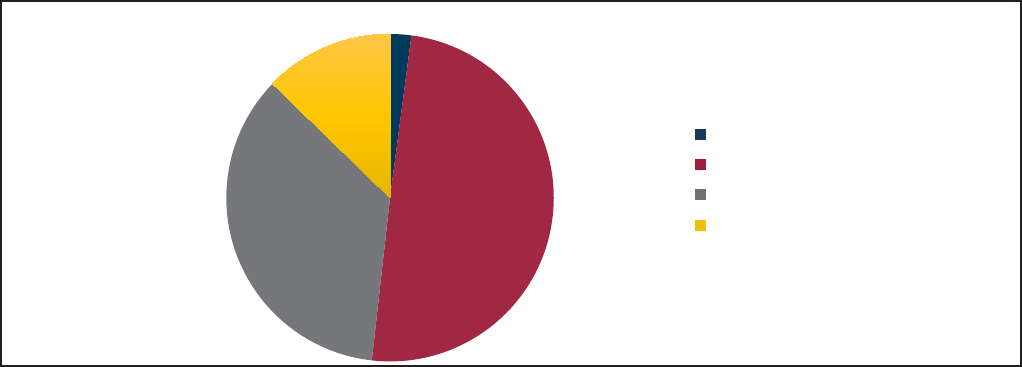

Exhibit 23: Average chronic absenteeism by grade level | 2017 through 2019

Source: OREA analysis of TDOE data.

From 2017 to 2019, the chronic absenteeism rate of all grade levels decreased with one exception: the chronic

absenteeism rate rose by 3 percent for 8th grade. e rate for 12th grade declined from 26.44 percent in 2017 to

23.81 percent in 2019, though the chronic absenteeism rate for 12th graders remained the highest of all grades.

Exhibit 24: Chronic absenteeism by grade level | 2017 through 2019

Source: OREA analysis of TDOE data.

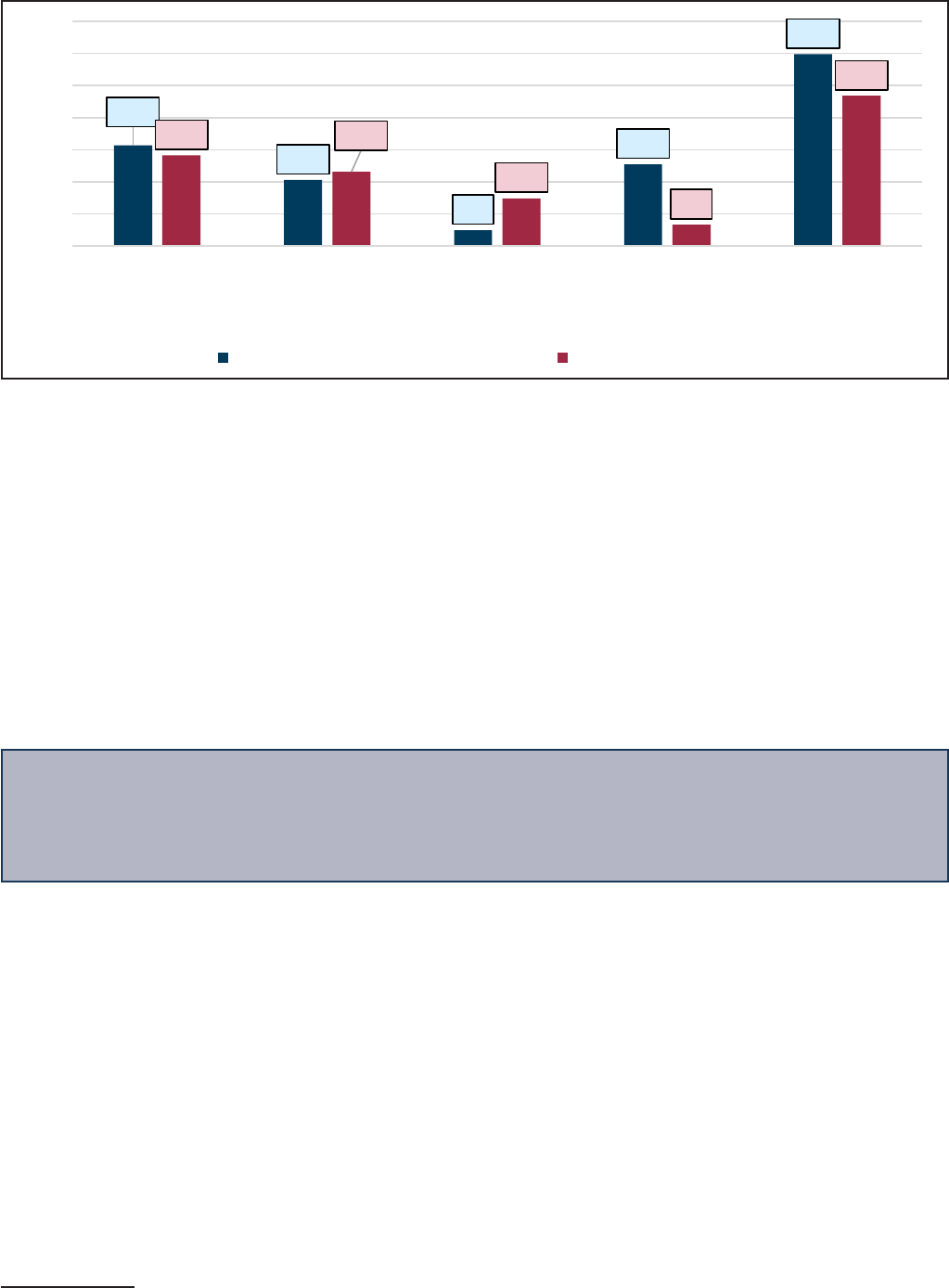

During the 2017, 2018, and 2019 school years, nearly half of all chronically absent students in Tennessee

were high school students. Twenty-six percent of all chronically absent students were middle schoolers, and

22 percent were 1st through 4th graders. e remaining 8 percent were kindergarten students. Kindergarten

students accounted for over 25 percent of all chronically absent elementary school students.

12.59%

10.18%

8.97%

8.47%

8.57%

8.65%

10.17%

11.77%

12.18%

14.49%

16.76%

19.24%

25.49%

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

K 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12 t h

2016-17

CA rate

2017-18

CA rate

2018-19

CA rate

3-year trend

in total # of

students

3-year trend

in total # of

CA students

3-year trend

of

CA rate

Kindergarten

12.68% 12.57% 12.53% +1,198 +37 -1.18%

1st grade

10.44% 10.27% 9.83% +1,028 -354 -5.87%

2nd grade

9.14% 8.96% 8.80% -330 -278 -3.69%

3rd grade

8.70% 8.46% 8.27% -3,449 -618 -4.95%

4th grade

8.73% 8.58% 8.41% -3,389 -542 -3.75%

5th grade

8.67% 8.63% 8.64% +975 +64 -0.31%

6th grade

10.21% 10.31% 10.00% +3,702 +209 -2.05%

7th grade

11.74% 11.98% 11.60% +2,843 +234 -1.18%

8th grade

11.98% 12.21% 12.35% +1,411 +449 +3.00%

9th grade

14.94% 14.40% 14.14% -32 -624 -5.39%

10th grade

16.72% 17.33% 16.23% -1,582 -610 -2.91%

11th grade

19.48% 19.44% 18.81% -1,296 -707 -3.42%

12th grade

26.44% 26.22% 23.81% +902 -1,520 -9.93%

27

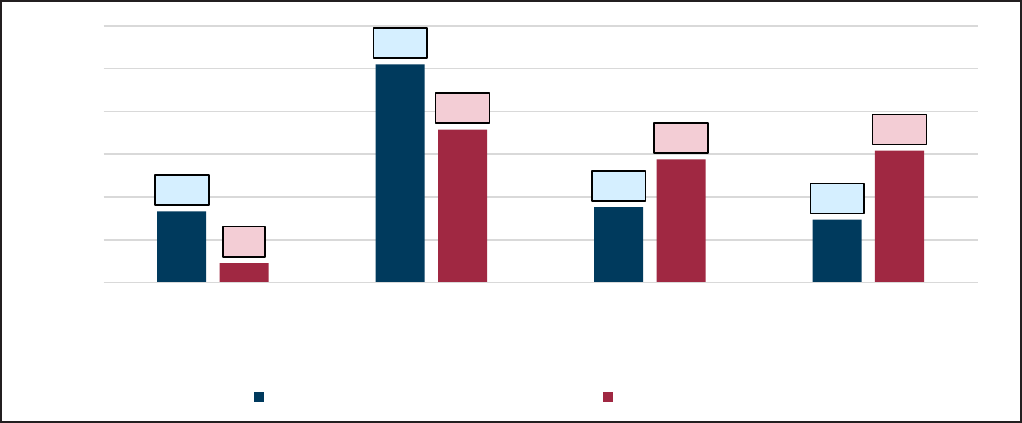

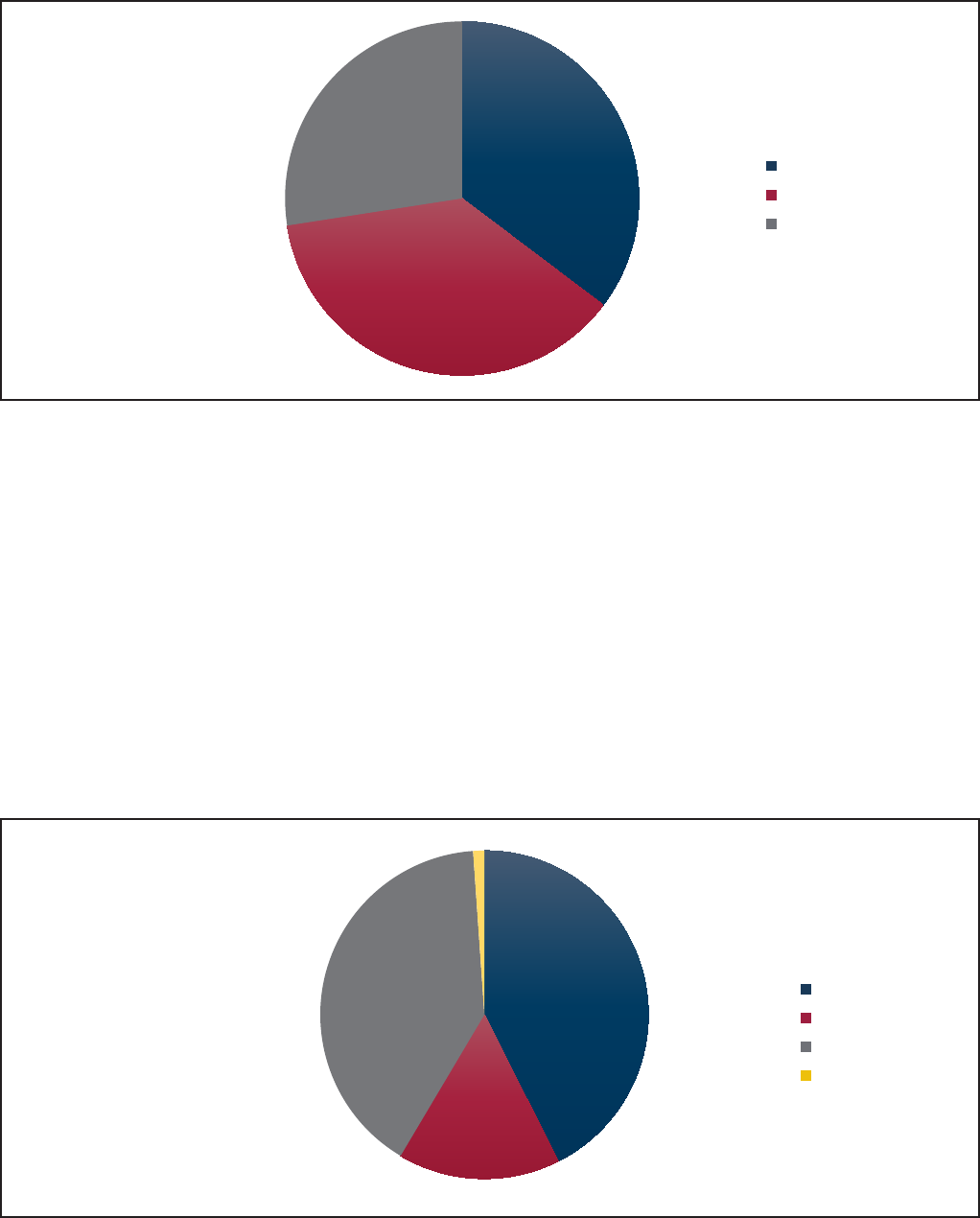

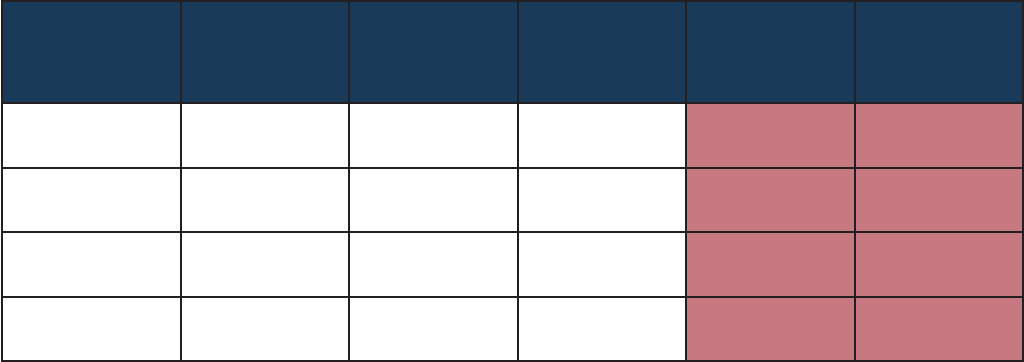

Exhibit 25: Average percentage of chronically absent students per grade | 2017 through 2019

Note: e number of students per grade level is a three-year average for 2017 through 2019.

Source: OREA analysis of TDOE data.

On the OREA survey of principals, respondents oered insight as to why certain grades may be more or less

likely to be chronically absent. In kindergarten, students are adjusting to a new schedule and an unfamiliar

environment and attendance is inconsistent for some students as a result. In addition, some younger students

are exposed to new germs upon entering kindergarten, leading to a higher number of absences due to illness,

according to principals.

In the higher grades, especially high school,

principals stated that some students start to miss

more school as they develop a more independent

life outside of school (e.g., driving themselves,

getting a job, etc.). Several principals specically

mentioned that high school seniors’ attendance

rates may decline because of decreased parental

supervision and an easier class schedule. In

addition, truancy laws no longer apply to

students who reach the age of 18, which occurs for some students during their senior year.

Some districts schedule graduation ceremonies before the nal day of school (i.e., before the 180th

instructional day of the school year), and students who discontinue attending classes after graduation are

counted as absent for any days remaining in the school year and may still be identied as chronically absent.

For example, high school graduation ceremonies were held early in one Tennessee school district in 2019, and

the chronic absenteeism rate for the school district’s 12th graders increased thereafter as graduating seniors

were absent for the eight days remaining in the school year.

9,427, 8%

27,129, 22%

32,191, 26%

53,933, 44%

Kindergarten 1st-4th 5th-8th 9th-12th

Kindergarten

1st-4th

5th-8th

9th-12th

“Seniors play the system for truancy. They learn and

push the envelope on the laws for school truancy. Once

students get close to or past 18 years old, they will miss at

their will, often do not correct when attendance becomes a

problem. I would like to see this law changed. If a student

turns 18 during their senior year, they must comply with

compulsory attendance laws.”

Respondent to OREA survey of principals, Dec. 2019

22%

26%

8%

28

Exhibit 26: Reasons for higher chronic absenteeism in certain grades, according to principals

Source: OREA survey of principals, December 2019.

Laws to combat absenteeism in upper grades

Two tools exist in law that school ocials may use to address excessive absenteeism among their older students.

Driver license suspension or revocation for excessive truancy

X

One tool available to address the absenteeism of older students

is to suspend or revoke their driver license. State law requires

directors of schools or the school district’s attendance supervisor

to notify the Department of Safety and Homeland Security (SHS)

when a student under the age of 18 accrues 10 consecutive, or

15 total, unexcused absences in a semester, at which point the

student’s learner’s permit or driver license is to be suspended or

denied (i.e., refusal upon rst application).

14

SHS shall notify

the student that his or her driver license or learner’s permit

(or ability to obtain either) has been suspended or denied.

Students then have 30 days to provide proof of compliance with

minimum attendance requirements through improved attendance,

graduation from high school, HiSET completion, emancipation, marriage, or an exemption (i.e., excused due

to circumstances beyond the student’s control). Students who comply with this step may regain their permit

or license by paying fees up to $95. Students who continue to be truant risk having their license revoked until

they graduate from high school, pass the HiSET, or reach the age of 18. State law authorizes school ocials to

report students who are not making satisfactory progress to SHS for license revocation.

Y

SHS is required by state law to annually report the number of students whose driver licenses have been

suspended for attendance or academic reasons, the number whose licenses were reinstated, and the total

number of licenses granted to students during the school year.

Z

In 2018-19, the department suspended 545

driver licenses for excessive truancy (i.e., withdrawn from school).

AA

,

AB

X

is report uses the term excessive truancy in place of withdrawn, which in law refers to a student who has missed 10 consecutive or 15 total unexcused absences in a semester.

Y

Satisfactory progress is dened in state law as making a passing grade in at least three full unit subjects or their equivalency at the conclusion of any grading period.

Z

By September 1 of each year, the department is required by law to report this information to both the House and Senate education committees.

AA